Narratives

Constitutional Law II

Michael Vernon Guerrero Mendiola

2005

Shared under Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Philippines license.

Some Rights Reserved.

Table of Contents

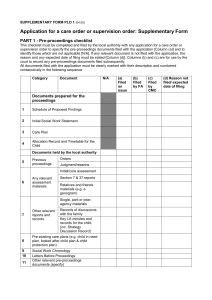

Duterte vs. Sandiganbayan [GR 130191, 27 April 1998] … 1

Tatad vs. Sandiganbayan [GR L-72335-39, 21 March 1988] … 2

Abardo vs. Sandiganbayan [GR 139571-72, 28 March 2001] … 4

Lopez vs. Office of the Ombudsman [GR 140529, 6 September 2001] … 6

Licaros vs. Sandiganbayan [GR 145851, 22 November 2001] … 8

This collection contains five (5) cases

summarized in this format by

Michael Vernon M. Guerrero (as a senior law student)

during the First Semester, school year 2005-2006

in the Political Law Review class

under Dean Mariano Magsalin Jr.

at the Arellano University School of Law (AUSL).

Compiled as PDF, September 2012.

Berne Guerrero entered AUSL in June 2002

and eventually graduated from AUSL in 2006.

He passed the Philippine bar examinations immediately after (April 2007).

berneguerrero.wordpress.com

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

349 Duterte vs. Sandiganbayan [GR 130191, 27 April 1998]

Third Division, Kapunan (J): 3 concur

Facts: In 1990, the Davao City Local Automation Project was launched by the city government of Davao.

The goal of said project was to make Davao City a leading center for computer systems and technology

development. It also aimed to provide consultancy and training services and to assist all local government

units in Mindanao set up their respective computer systems. To implement the project, a Computerization

Program Committee, composed of the following was formed: Atty. Benjamin C. de Guzman (City

Administrator) as Chairman; and Mr. Jorge Silvosa (Acting City Treasurer), Atty. Victorino Advincula (City

Councilor), Mr. Alexis Almendras (City Councilor), Atty. Onofre Francisco (City Legal Officer), Mr. Rufino

Ambrocio, Jr. (Chief of Internal Control Office), and Atty. Mariano Kintanar (COA Resident Auditor) as

members. The Committee recommended the acquisition of Goldstar computers manufactured by Goldstar

Information and Communication, Ltd., South Korea and exclusively distributed in the Philippines by Systems

Plus, Inc. (SPI), the total contract cost amounting to P11,656,810.00. On 5 November 1990, the City Council

(Sangguniang Panlungsod) of Davao unanimously passed Resolution 1402 and Ordinance 173 approving the

proposed contract for computerization between Davao City and SPI. The Sanggunian, likewise, authorized the

City Mayor (Rodrigo R. Duterte) to sign the said contract for and in behalf of Davao City. On the same day,

the Sanggunian issued Resolution 1403 and Ordinance 174, the General Fund Supplemental Budget 07 for

CY 1990 appropriating P3,000,000.00 for the city's computerization project. Sometime in February 1991, a

complaint (Civil Case 20,550-91), was instituted before the Regional Trial Court of Davao City, Branch 12 by

Dean Pilar Braga, Hospicio C. Conanan, Jr. and Korsung Dabaw Foundation, Inc. against the Duterte, de

Guzman, the City Council, various city officials and SPI for the judicial declaration of nullity of the

resolutions and ordinances and the computer contract executed pursuant thereto with SPI. On 22 February

1991, Goldstar, through its agent, Mr. S.Y. Lee sent a proposal to Duterte for the cancellation of the

computerization contract. Consequently, on 8 April 1991, the Sanggunian issued Resolution 449 and

Ordinance 53 accepting Goldstar's offer to cancel the computerization contract provided the latter return the

advance payment of P1,748,521.58 to the City Treasurer's Office within a period of 1 month. On 6 May 1991,

Duterte, in behalf of Davao City, and SPI mutually rescinded the contract and the downpayment was duly

refunded. The city government, intent on pursuing its computerization plan, following the recommendation of

Special Audit Team of the Commission on Audit, sought the assistance of the National Computer Center

(NCC). The NCC recommended the acquisition of Philips computers in the amount of P15,792,150.00. Davao

City complied with the NCC's advice and hence, was finally able to obtain the needed computers. On 1

August 1991, the Anti-Graft League-Davao City Chapter, through one Miguel C. Enriquez, filed an unverified

complaint with the Ombudsman-Mindanao against Duterte and de Guzman, the City Treasurer, City Auditor,

the whole city government of Davao and SPI, alleging that the latter, in entering into the computerization

contract, violated RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), PD 1445 (Government Auditing Code of

the Philippines), COA circulars and regulations, the Revised Penal Code and other pertinent penal laws

(OMB-3- 91-1768). On 14 October 1991, Judge Paul T. Arcangel, issued an Order dismissing Civil Case

20,550-91. On 12 November 1991, Graft Investigator Manriquez issued an order in OMB-3-91-1768 directing

Jorge Silvosa (City Treasurer), Mariano Kintanar (City Auditor) and Manuel T. Asis of SPI to file in 10 days

their respective verified point-by-point comment under oath upon every allegation of the complaint in Civil

Case 20,550-91. On 4 December 1991, the Ombudsman received the affidavits of the Special Audit Team but

failed to furnish Duterte, et. al. copies thereof. On 18 February 1992, Duterte, et. al. submitted a manifestation

adopting the comments filed by Jorge Silvosa and Mariano Kintanar dated 25 November 1991 and 17 January

1992, respectively. Four years after, or on 22 February 1996, Duterte, et.al. received a copy of a Memorandum

prepared by Special Prosecution Officer I, Lemuel M. De Guzman dated 8 February 1996 addressed to

Ombudsman Aniano A. Desierto regarding OMB-MIN-90-0425 and OMB-3-91-1768. Instead of the charges

of malversation, violation of Sec. 3(e), R.A. No. 3019 and Art. 177, Revised Penal Code, Prosecutor De

Guzman recommended that Duterte, et. al. be charged under Sec. 3(g) of RA 3019 "for having entered into a

contract manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to the government, the elements of profit, unwarranted

benefits or loss to government being immaterial." Accordingly, Duterte, et. al. were charged before the

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 1 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

Sandiganbayan in an information dated 8 February 1996 (Criminal Case 23193). On 27 February 1996,

Duterte, et. al. filed a motion for reconsideration and on 29 March 1996, a Supplemental Motion for

Reconsideration on the ground that, among others, "petitioners were deprived of their right to a preliminary

investigation, due process and the speedy disposition of their case." On 19 March 1996, the Ombudsman

issued a Resolution denying Duterte, et. al.'s motion for reconsideration. On 18 June 1997, Duterte, et. al.

filed a Motion to Quash which was denied by the Sandiganbayan in its Order dated 27 June 1997. On 15 July

1997, Duterte, et. al. moved for reconsideration of the above order but the same was denied by the

Sandiganbayan for lack of merit in its Resolution dated 5 August 1997. Duterte and de Guzman filed a special

civil action for certiorari with preliminary injunction with the Supreme Court.

Issue: Whether there was unreasonable delay in the termination of the irregularly conducted preliminary

investigation.

Held: Compounding the deprivation of Duterte's and de Guzman's right to a preliminary investigation was the

undue and unreasonable delay in the termination of the irregularly conducted preliminary investigation. Their

manifestation adopting the comments of their co-respondents was filed on 18 February 1992. However, it was

only on 22 February 1996 or 4 years later, that they received a memorandum dated 8 February 1996 submitted

by Special Prosecutor Officer I Lemuel M. De Guzman recommending the filing of information against them

for violation of Sec. 3(g) of RA 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act). The inordinate delay in the

conduct of the "preliminary investigation" infringed upon their constitutionally guaranteed right to a speedy

disposition of their case. Further, the constitutional right to speedy disposition of cases does not come into

play only when political considerations are involved. The Constitution makes no such distinction. While

political motivation in Tatad may have been a factor in the undue delay in the termination of the preliminary

investigation therein to justify the invocation of their right to speedy disposition of cases, the particular facts

of each case must be taken into consideration in the grant of the relief sought. Duterte, et. al. herein could not

have urged the speedy resolution of their case because they were completely unaware that the investigation

against them was still on-going. Peculiar to this case is the fact that Duterte, et. al. were merely asked to

comment, and not file counter-affidavits which is the proper procedure to follow in a preliminary

investigation. After giving their explanation and after four long years of being in the dark, they, naturally, had

reason to assume that the charges against them had already been dismissed. On the other hand, the Office of

the Ombudsman failed to present any plausible, special or even novel reason which could justify the four-year

delay in terminating its investigation. Its excuse for the delay — the many layers of review that the case had

to undergo and the meticulous scrutiny it had to entail — has lost its novelty and is no longer appealing. The

incident herein does not involve complicated factual and legal issues, specially in view of the fact that the

subject computerization contract had been mutually cancelled by the parties thereto even before the AntiGraft League filed its complaint. The Office of the Ombudsman capitalizes on Duterte, et. al.'s three motions

for extension of time to file comment which it imputed for the delay. However, the delay was not caused by

the motions for extension. The delay occurred after petitioners filed their comment. Between 1992 to 1996,

Duterte, et. al. were under no obligation to make any move because there was no preliminary investigation

within the contemplation of Section 4, Rule II of A.O. No. 07 to speak of in the first place. Hence, the petition

was granted.

350 Tatad vs. Sandiganbayan [GR L-72335-39, 21 March 1988]

En Banc, Yap (J): 14 concur

Facts: Sometime in October 1974, Antonio de los Reyes, former Head Executive Assistant of the then

Department of Public Information (DPI) and Assistant Officer-in-Charge of the Bureau of Broadcasts, filed a

formal report with the Legal Panel, Presidential Security Command (PSC), charging Francisco S. Tatad, who

was then Secretary and Head of the Department of Public Information, with alleged violations of Republic

Act 3019, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. Apparently, no action was taken on

said report. Then, in October 1979, or 5 years later, it became publicly known that Tatad had submitted his

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 2 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

resignation as Minister of Public Information, and 2 months after, or on 12 December 1979, Antonio de los

Reyes filed a complaint with the Tanodbayan (TBP Case 8005-16-07) against Tatad, accusing him of graft and

corrupt practices in the conduct of his office as then Secretary of Public Information. The complaint repeated

the charges embodied in the previous report filed by complaint before the Legal Panel, Presidential Security

Command (PSC). On 26 January 1980, the resignation of Tatad was accepted by President Ferdinand E.

Marcos. On 1 April 1980, the Tanodbayan referred the complaint of Antonio de los Reyes to the Criminal

Investigation Service (CIS) for fact-finding investigation. On 16 June 1980, Roberto P. Dizon, CIS

Investigator of the Investigation and Legal Panel, PSC, submitted his Investigation Report, with the following

conclusion, "evidence gathered indicates that former Minister Tatad had violated Sec. 3 (e) and Sec. 7 of RA

3019, respectively. On the other hand, Mr. Antonio L. Cantero is also liable under Sec. 5 of RA 3019," and

recommended appropriate legal action on the matter. Tatad moved to dismiss the complaint against him,

claiming immunity from prosecution by virtue of PD 1791, but the motion was denied on 26 July 1982 and

his motion for reconsideration was also denied on 5 October 1982. On 25 October 1982, all affidavits and

counter-affidavits were with the Tanodbayan for final disposition. On 5 July 1985, the Tanodbayan approved a

resolution, dated 1 April 1985, prepared by Special Prosecutor Marina Buzon, recommending that the

informations be filed against Tatad before the Sandiganbayan, for (1) violation of Section 3, paragraph (e) of

RA 3019 for giving D'Group, a private corporation controlled by his brother-in-law, unwarranted benefits,

advantage or preference in the discharge of his official functions through manifest partiality and evident bad

faith; (2) violation of Section 3, paragraph (b) of R.A. 3019 for receiving a check of P125,000.00 from

Roberto Vallar, President/General Manager of Amity Trading Corporation as consideration for the release of a

check of P588,000.00 to said corporation for printing services rendered for the Constitutional Convention

Referendum in 1973; and (3) violation of Section 7 of R.A. 3019 on three (3) counts for his failure to file his

Statement of Assets and Liabilities for the calendar years 1973, 1976 and 1978." Accordingly, on 12 June

1985, informations were filed with the Sandiganbayan against Tatad (Criminal cases 10499 to 10503). On 22

July 1985, Tatad filed with the Sandiganbayan a consolidated motion to quash the information on the ground

that, among others, "the prosecution deprived accused-movant of due process of law and of the right to a

speedy disposition of the cases filed against him, amounting to loss of jurisdiction of file the informations."

On 26 July 1985, the Tanodbayan filed its opposition to petitioner's consolidated motion to quash. On August

9, 1985, the Sandiganbayan rendered its resolution denying Tatad's motion to quash. On 10 August 1985, the

Tanodbayan filed an amended information in Criminal Case 10500, changing the date of the commission of

the offense to 30 September 1974. On 30 August 1985, Tatad filed a consolidated motion for reconsideration

which was denied by the Sandiganbayan on 17 September 1985. On 16 October 1985, Tatad filed a petition

for certiorari and prohibition, with preliminary injunction, before the Supreme Court.

Issue: Whether the long delay in teh termination of the preliminary investigation by the Tanodbayan violated

tatad’s rights to due process and speedy disposition of cases.

Held: A painstaking review of the facts can not but leave the impression that political motivations played a

vital role in activating and propelling the prosecutorial process in this case. Firstly, the complaint came to life,

as it were, only after petitioner Tatad had a falling out with President Marcos. Secondly, departing from

established procedures prescribed by law for preliminary investigation, which require the submission of

affidavits and counter-affidavits by the Tanodbayan referred the complaint to the Presidential Security

Command for fact-finding investigation and report. The Court cannot emphasize too strongly that prosecutors

should not allow, and should avoid, giving the impression that their noble office is being used or prostituted,

wittingly or unwittingly, for political ends or other purposes alien to, or subversive of, the basic and

fundamental objective of serving the interest of justice evenhandedly, without fear or favor to any and all

litigants alike, whether rich or poor, weak or strong, powerless or mighty. Only by strict adherence to the

established procedure may the public's perception of the impartiality of the prosecutor be enhanced. Coming

into the main point, the long delay in the termination of the preliminary investigation by the Tanodbayan is

violative of the constitutional right of the accused to due process. Substantial adherence to the requirements of

the law governing the conduct of preliminary investigation, including substantial compliance with the time

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 3 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

limitation prescribed by the law for the resolution of the case by the prosecutor, is part of the procedural due

process constitutionally guaranteed by the fundamental law. Not only under the broad umbrella of the due

process clause, but under the constitutional guarantee of "speedy disposition" of cases as embodied in Section

16 of the Bill of Rights (both in the 1973 and 1987 Constitution), the inordinate delay is violative of Tatad's

constitutional rights. A delay of close to 3 years can not be deemed reasonable or justifiable in the light of the

circumstances obtaining in the present case. The Court is not impressed by the attempt of the Sandiganbayan

to sanitize the long delay by indulging in the speculative assumption that "the delay may be due to a

painstaking and grueling scrutiny by the Tanodbayan as to whether the evidence presented during the

preliminary investigation merited prosecution of a former high-ranking government official." In the first

place, such a statement suggests a double standard of treatment, which must be emphatically rejected.

Secondly, three out of the five charges against Tatad were for his alleged failure to file his sworn statement of

assets and liabilities required by RA 3019, which certainly did not involve complicated legal and factual

issues necessitating such "painstaking and grueling scrutiny" as would justify a delay of almost three years in

terminating the preliminary investigation. The other two charges relating to alleged bribery and alleged giving

of unwarranted benefits to a relative, while presenting more substantial legal and factual issues, certainly do

not warrant or justify the period of three years, which it took the Tanodbayan to resolve the case. After a

careful review of the facts and circumstances of the case, the Court was constrained to hold that the inordinate

delay in terminating the preliminary investigation and filing the information in the instant case is violative of

the constitutionally guaranteed right of Tatad to due process and to a speedy disposition of the cases against

him. Accordingly, the informations in Criminal Cases 10499, 10500, 10501, 10502 and 10503 should be

dismissed.

351 Abardo vs. Sandiganbayan [GR 139571-72, 28 March 2001]

Third Division, Gonzaga-Reyes (J): 4 concur

Facts: On 21 May 1991, the Office of the Ombudsman filed before the Sandiganbayan two separate

informations for falsification of public documents (Criminal Cases 16744 and 16745) against Roger N.

Abardo who was then the provincial assessor of Camarines Sur. The information in Criminal Case 167444

charged Abardo and six others with falsifying Tax Declarations 008-13, 008-14, 008-15, 008-17, 008-18, 00819, 008-20 and 008-21 on or about 8 December 1988 by making it appear that property consisting of 1,887

hectares had been declared in the name of the United Coconut Planters Bank (UCPB) since 1985 and that,

having been reclassified to first-class unirrigated land, the market value thereof has increased to P16,008.00

per hectare when in fact said property, which was formerly classified as pasture land under Tax Declarations

3915 and 3916 issued in the name of Rosita Alberto, had a market value of only P1,524.00 per hectare and

was declared in the name of UCPB only in 1988. The same property was subsequently transferred by UCPB

to Sharp International Marketing (Phil.) Inc. (Sharp) and the tax declarations issued in the name of Sharp are

the subject of Criminal Case 167455. In the latter case, Abardo and five others were charged with falsifying

Tax Declarations 008-22 to 008-29 on or about 8 December 1988, by making it appear that the property

covered therein was transferred from UCPB to Sharp, and by also increasing its appraisal to first-class

unirrigated riceland when in truth and in fact the same is cogonal and mountainous. At the scheduled

arraignment on 8 July 1991, Abardo filed a Motion to Quash on the grounds that the facts charged in the

informations do not constitute the crime of falsification of public documents; that the informations contain

averments which constitute a legal excuse or justification; and that the criminal offense of falsification of

public documents cannot be validly filed against Abardo. In view of the pendency of the said motions,

Abardo’s arraignment was postponed until further notice. On 24 July 1991, the Office of the Special

Prosecutor filed an Opposition to Abardo’s Motion to Quash. On 3 September 1991, the Sandiganbayan

issued a Resolution denying the Motion to Quash for lack of merit. A motion to reconsider the said resolution

was denied. Eventually, Abardo filed with the Supreme Court a Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition seeking

to set aside the Resolution issued by the Sandiganbayan on 3 September 1991 denying his motion to quash.

As a consequence, the arraignment scheduled for 7 October 1991 was reset to 28 November 1991, upon

motion of Abardo’s counsel. Thereafter, Abardo’s arraignment was reset several times upon motion of his

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 4 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

counsel and for the same reason. Thereafter, in an Order dated 28 May 1992, Abardo's arraignment was

cancelled and reset to 28 July 1992, in view of the reorganization of the Sandiganbayan. In a Resolution dated

5 March 1992, the Supreme Court dismissed the petition, no grave abuse of discretion being imputable to the

Sandiganbayan. Similarly, the motion for reconsideration filed by Abardo was denied.

On 28 July 1992, Abardo was arraigned and pleaded not guilty to both cases. On even date, the

Sandiganbayan issued an Order setting the trial of Abardo "on the date of trial of his co-accused whose cases

are being reinvestigated." In a letter dated 20 March 1997 to the Office of the Ombudsman, Abardo requested

for the payment of his retirement benefits which had been withheld since his compulsory retirement in 1994

due to the pendency of the subject criminal cases. This letter was brought to the attention of the

Sandiganbayan in a letter dated 22 September 1997. In a Resolution adopted on 4 November 1997, the

Sandiganbayan set for a conference all the lawyers of the defense and the prosecution to see how these cases

can move faster. On 7 January 1998, co-accused Salvador P. Pejo filed a Motion for Leave to Participate in

the Reinvestigation of the Cases which was granted in an Order dated 9 January 1998. In an Order dated 27

January 1998, the Sandiganbayan gave the prosecution a period of 60 days to conduct a thorough

reinvestigation of Criminal Cases 16739 to 16749 involving all the accused therein and ordering it to submit

its report within the same period containing its findings and recommendation together with the action taken

by the Ombudsman. On 12 August 1998, Abardo filed a Motion to Dismiss and/or Motion for Reinvestigation

on the ground that "the ultimate purchase by the Philippine government of the Garchitorena estate at the price

of P33,000.00 has veritably rendered all the pending criminal cases moot and academic." On 12 October

1998, Abardo filed a Supplemental Motion to Dismiss on the ground that the criminal cases should be

dismissed to implement the provisions of RA 8493, otherwise known as the Speedy Trial Act of 1998,

considering that the two pending criminal cases against him have already exceeded the extended time limit

under Section 7 of Supreme Court Circular 38-98." On 1 December 1998, Abardo filed a Motion for Early

Resolution to speed up the early judgment and resolution of the cases. In a Resolution dated 1 December

1998, the Sandiganbayan denied for lack of merit Abardo’s two motions (Motion to Dismiss and/or Motion

for Reinvestigation and the Supplemental Motion to Dismiss). His motion for reconsideration was likewise

denied in a Resolution dated 16 July 1999. Abardo filed a Petition for Review on Certiorari before the

Supreme Court.

Issue: Whether the Speedy Trial Act should apply to dispose the cases, which remain pending after a

considerably prolonged delay.

Held: Unreasonable delay in the disposition of cases in judicial, quasi-judicial and administrative bodies is a

serious problem besetting the administration of justice in the country. As one solution on the problem of delay

in the disposition of criminal cases, Republic Act 8493, otherwise known as the "Speedy Trial Act of 1998",

intended to ensure a speedy trial of all criminal cases before the Sandiganbayan. Regional Trial Court,

Metropolitan Trial Court and Municipal Circuit Trial Court was passed by the Senate and the House of

Representatives on 4 February 1998 and 3 February 1998, respectively. Supreme Court Circular 38-98 which

was promulgated for the purpose of implementing the provisions thereof took effect on 15 September 1998.

The time limits provided by RA 8493 could not be applied to the present case as Abardo was arraigned way

back in 28 July 1992. At that time, there was yet no statute which establishes deadlines for arraignment and

trial; and the time limits for trial imposed by RA 8493 are reckoned from the arraignment of the accused.

Nevertheless, RA 8493 does not preclude application of the provision on speedy trial in the Constitution.

Indeed, in determining whether Abardo’s right to a speedy trial has been violated, resort to Section 16, Article

III of the 1987 Constitution is imperative. It provides that "All persons shall have the right to speedy

disposition of their cases before all judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative bodies." The Constitution

mandates dispatch not only in the trial stage, but also in the disposition thereof, warranting dismissals in cases

of violations thereof without the fault of the party concerned, not only the accused. However, the right of an

accused to a speedy trial should not be utilized to deprive the state of a reasonable opportunity of fairly

indicting criminals. Herein, the records disclose that the two informations against petitioner were filed almost

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 5 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

a decade ago or way back on 21 May 1991. What glares from the records is that from his arraignment on said

date, there was an unexplained interval or inactivity of close to five years in the Sandiganbayan.

Consequently, on 27 March 1997, Abardo brought to the attention of the Ombudsman the withholding of his

retirement benefits and that no hearing of the case has yet been conducted. Granting that the delay or interval

was caused by the separate motions for reinvestigation filed by the different accused, again, there is no

explanation why the reinvestigation was unduly stretched beyond a reasonably permissible time frame.

Apparently, the Office of the Ombudsman did not complete the reinvestigation during the five-year interval. It

is apparent that the delay is not solely or even equally chargeable to petitioner, but to the Office of the

Ombudsman where the conduct of the reinvestigation has languished for an unreasonable length of time.

Clearly, the delay disregarded the Ombudsman’s duty, as mandated by the Constitution and RA 6770, to

enforce the criminal liability of government officers or employees in every case where the evidence warrants

in order to promote efficient service to the people. The fact that up to this time no trial has been set,

apparently due to the inability of the Ombudsman to complete the reinvestigation is a distressing indictment

of the criminal justice system, particularly its investigative and prosecutory pillars. Hence, the Court grants

the petition and directed the Sandiganbayan to dismiss Criminal Cases 16744 and 16745.

352 Lopez vs. Office of the Ombudsman [GR 140529, 6 September 2001]

Third Division, Gonzaga-Reyes (J): 4 concur

Facts: On 30 June 1959, Jose P. Lopez Jr. started working with the DECS as a classroom teacher. Through

hard work, exemplary performance and continuous studies, he was promoted and assigned to different

positions such as Special Education Teacher; Child and Youth Specialist; 2nd Lt., 36 Battalion Combat Team,

Philippine Army (Reserved Force); Asst. Director and concurrent Director, Child and Youth Research Center

(now a defunct office); and finally, he was appointed as Administrative Officer V, DECS-Region XII,

Cotabato City. Among Lopez' tasks as Administrative Officer V is to determine whether certain expenses are

necessary in the attainment of the objectives of the DECS-Region XII and to pass upon, review and evaluate

documents and other supporting papers submitted to him in relation to his duties. Between 1992 and 1993,

DECS-Region XII ordered several pieces of laboratory equipment and apparati requested by different school

divisions of the region. The concerned officers of DECS-Region XII submitted to Lopez the documents

covering the transactions. After careful scrutiny of the documents submitted to him, Lopez affixed his

signature on the disbursements vouchers that were accompanied by Purchase Orders, Sales Invoices,

Delivery/Memorandum Receipts and proof that the transactions were post audited by the COA Resident

Auditor who found them in order. Disregarding the findings of the COA Resident Auditor - DECS Region

XII, Cotabato City, who post audited the transactions and found them in order, for reasons of his own, the

COA Regional Director formed a Special Audit Team to investigate and audit the transactions. Without

seeking the presence of the concerned officials and employees of DECS – Region XII, the COA Special Audit

Team conducted an audit of the transactions. On 20 December 1993, the members of the COA Special Audit

Team submitted to the COA Regional Director-Region XII, their Joint Affidavit claiming alleged deficiencies

in the transactions of DECS – Region XII implicating thereto Lopez and some concerned officials and

employees of DECS-Region XII. Dispensing conducting an exit conference and inviting Lopez to clarify the

allegations of the COA Special Audit Team in their Joint Affidavit-Complaint, in post-haste the COA

Regional Directors indorsed it to the Office of the Ombudsman-Mindanao for preliminary investigation (Case

3-93-27791, for Falsification of Documents by Public Officers). In her Order dated 1 March 1994, Graft

Investigation Officer (GIO) Marie Dinah Tolentino directed the petitioner to submit a Counter-Affidavit

without informing him of his constitutional right to counsel. On 14 April 1994, without the assistance of

counsel, Lopez wrote the Office of the Ombudsman-Mindanao requesting for an extension of 10 days from 19

April 1994 to submit his Counter-Affidavit. On 19 April 1994, Atty. Edgardo A. Camello, counsel for Makil

Pundaodaya and the other respondents in Case OMB-3-93-8791 filed a Motion for Extension of Time to

submit their Counter-Affidavits. On 22 April 1994, without the assistance of counsel, Lopez submitted to the

Office of Ombudsman-Mindanao his Counter-Affidavit he personally prepared denying specifically each and

every criminal act attributed to him by the Commission on Audit. Although Lopez did not submit any written

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 6 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

statement authorizing Atty. Camello to represent him in Case OMB 3-93-8791, the Office of the OmbudsmanMindanao erroneously assumed or deliberately made to appear that he was represented by said attorney. As a

consequence thereof, the Office of Ombudsman-Mindanao did not notify him of the progress of the

preliminary investigation. More than 4 years after he submitted his Counter-Affidavit, Lopez was surprised

that, without preliminary investigation and clarificatory question asked, on 17 July 1998, the Office of the

Ombudsman-Mindanao terminated the preliminary investigation recommending that he, together with the

other respondents in Case OMB 3-93-9791, be prosecuted for violation of Sec. 3(e) and (g) of the Anti-Graft

and Corrupt Practices Act. Within the reglementary period, without the assistance of counsel, Lopez sent a

letter to the Office of the Ombudsman-Mindanao dated 8 June 1999 seeking the reconsideration of the

Resolution in Case OMB 33-93-2791 wherein he stressed that he was deprived of due process and that there

was inordinate delay in the resolution of the preliminary investigation; and there was no exit conference

wherein he could have explained to the Graft Investigation Officer his exculpatory participation in the

transactions investigated. In addition, he also submitted to the Office of the Ombudsman-Mindanao a Motion

for Reconsideration or Reinvestigation reiterating the allegations mentioned in his letter dated 8 June 1999.

Unfortunately, said Motion for Reconsideration or Reinvestigation was not acted upon by the Office of the

Ombudsman-Mindanao by giving the excuse that its Resolution was already forwarded to Ombudsman

Aniano Desierto. Lopez filed a petition for mandamus seeking (1) the dismissal of Ombudsman Case OMB-393-2793 (now Criminal Cases 25247-25226); and (2) the issuance of a clearance in his favor.

Issue: Whether the cases against Lopez should be dismissed in light of his constitutional right to speedy trial.

Held: The constitutional right to a "speedy disposition of cases" is not limited to the accused in criminal

proceedings but extends to all parties in all cases, including civil and administrative cases, and in all

proceedings, including judicial and quasi-judicial hearings. Hence, under the Constitution, any party to a case

may demand expeditious action on all officials who are tasked with the administration of justice. However,

the right to a speedy disposition of a case, like the right to speedy trial, is deemed violated only when the

proceedings is attended by vexatious, capricious, and oppressive delays; or when unjustified postponements

of the trial are asked for and secured, or even without cause or justifiable motive a long period of time is

allowed to elapse without the party having his case tried. Equally applicable is the balancing test used to

determine whether a defendant has been denied his right to a speedy trial, or a speedy disposition of a case for

that matter, in which the conduct of both the prosecution and the defendant is weighed, and such factors as the

length of the delay, the reasons for such delay, the assertion or failure to assert such right by the accused, and

the prejudice caused by the delay. The concept of speedy disposition is a relative term and must necessarily be

a flexible concept. Herein, the preliminary investigation was resolved close to 4 years from the time all the

counter and reply affidavits were submitted to the Office of the Ombudsman. After the last reply-affidavit was

filed on 28 February 1995, it was only on 17 July 1998 that a resolution was issued recommending the filing

of the corresponding criminal informations against Lopez and the others. It took 8 months or on 27 February

1999 for Deputy Ombudsman Margarito P. Gervacio, Jr. to approve the same and close to another year or on

30 April 1999 for Ombudsman Aniano Desierto to approve the recommendation. During this interval, no

incidents presented themselves for resolution and the delay could only be attributed to the inaction on the part

of the investigating officials. Indeed, without cause or justifiable motive, a long period of time was allowed to

elapse at the preliminary investigation stage before the informations were filed. The cases are not sufficiently

complex to justify the length of time for their resolution. Neither can the long delay in resolving the case

under preliminary investigation be justified on the basis of the number of informations filed before the

Sandiganbayan nor of the transactions involved. The thirty informations consist of 16 counts of violations of

Section 3 (g) of RA 3019 relative to the overpricing and lack of public bidding of laboratory apparatus and

school equipment; while the 14 counts are for violations of Section 3 (e) of the same law relative to the

certification in the inspection reports that the subject items have already been delivered and received, when in

fact they have not yet been actually delivered and received, in order to facilitate payment to the suppliers.

There is no statement that voluminous documentary and testimonial evidence were involved. Verily, the delay

disregarded the Ombudsman’s duty, as mandated by the Constitution and Republic Act 6770, to enforce the

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 7 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

criminal liability of government officers or employees in every case where the evidence warrants in order to

promote efficient service to the people. The failure of said office to resolve the complaints that have been

pending for almost four years is clearly violative of this mandate and the rights of petitioner as a public

official. In such event, Lopez is entitled to the dismissal of the cases filed against him.

353 Licaros vs. Sandiganbayan [GR 145851, 22 November 2001]

En Banc, Panganiban (J): 14 concur

Facts: On 5 June 1982, the Legaspi City Branch of the Central Bank was robbed and divested of cash in the

amount of P19,731,320.00. In the evening of 6 June 1982, Modesto Licaros (no relation to Abelardo B.

Licaros), one of the principal accused, together with four companions, delivered in sacks a substantial portion

of the stolen money to the Concepcion Building in Intramuros, Manila where Home Savings Bank had its

offices, of which Abelardo Licaros was then Vice Chairman and Treasurer. The delivery was made on

representation by Modesto Licaros to former Central Bank Governor Gregorio Licaros, Sr., then Chairman of

the Bank and father of Abelardo, that the money to be deposited came from some Chinese businessmen from

Iloilo who wanted the deposit kept secret; that Governor Licaros left for the United States on 28 May 1982 for

his periodic medical check-up, so left to his son, Abelardo, to attend to the proposed deposit. Abelardo

attempted to report the incident to General Fabian Ver but he could not get in touch with him because the

latter was then out of the country. It was only the following day, 9 June 1982, when Abelardo was able to

arrange a meeting with then Central Bank Governor Jaime C. Laya, Senior Deputy Governor Gabriel Singson,

and Central Bank Chief Security Officer, Rogelio Navarete, to report his suspicion that the money being

deposited by Modesto Licaros may have been stolen money. With the report or information supplied by

Abelardo, then CB Governor Laya called up then NBI Director Jolly Bugarin and soon after the meeting, the

NBI, Metrocom and the CB security guards joined forces for the recovery of the money and the apprehension

of the principal accused. All the aforesaid Central Bank officials executed sworn statements and testified for

Abelardo, particularly CB Governor Jaime C. Laya, CB Senior Deputy Governor Gabriel Singson and CB

Director of the Security and Transport Department Rogelio Navarette, and were one in saying that it was the

report of Abelardo to the authorities that broke the case on 9 June 1982 and resulted in the recovery of the

substantial portion of the stolen money and the arrest of all the principal accused.

On 6 July 1982, after preliminary investigation, the Tanodbayan (now Special Prosecutor) filed an

Information for robbery with the Sandiganbayan (Criminal Case 6672) against two groups of accused: (a)

Principals: Modesto Licaros y Lacson (Private Individual), Leo Flores y Manlangit (CB Security Guard),

Ramon Dolor y Ponce (CB Assistant Regional Cashier), Glicerio Balansin y Elaurza (CB Security Guard),

Rolando Quejada y Redequillo (Private Individual), Pio Edgardo Flores y Torres (Private Individual), Mario

Lopez Vito y Dayungan (Private Individual), and Rogelio De la Cruz y Bodegon (Private Individual); and (b)

Accessory After the Fact: Abelardo B. Licaros (Vice Chairman and Treasurer, Home Savings Bank and Trust

Co. (HSBTC), Private Individual). On 26 November 1982, the Tanodbayan filed an Amended Information

naming the same persons as principals, except Rogelio dela Cruz who is now charged as an accessory,

together with Abelardo. De la Cruz died on 6 November 1987 as per manifestation by his counsel dated and

filed on 17 November 1987. On 29 November 1982, the accused were arraigned, including Abelardo, who

interposed the plea of not guilty. On 7 January 1983, the Tanodbayan filed with the Sandiganbayan a "Motion

for Discharge" of Abelardo to be utilized as a state witness which was granted in a Resolution dated 11

February 1983. The Supreme Court, however, on petition for certiorari filed by accused Flores, Modesto

Licaros and Lopez Vito, annulled the discharge because it ruled that the Sandiganbayan should have deferred

its resolution on the motion to discharge until after the prosecution has presented all its other evidence.

At the close of its evidence, or on 23 July 1984, the prosecution filed a second motion for discharge of

Abelardo to be utilized as a state witness but the Sandiganbayan in a Resolution dated 13 September 1984

denied the Motion stating in part that the motion itself does not furnish any cue or suggestion on what

petitioner will testify in the event he is discharged and placed on the stand as state witness. Meanwhile, as of

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 8 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

8 March 1983, the prosecution has presented 10 witnesses. None of the witnesses, nor any of the principal

accused who executed the sworn statements implicated Abelardo to the crime of robbery directly or indirectly.

On 17 September 1984, the prosecution formally offered its documentary evidence. In a Resolution dated 1

October 1984, the Sandiganbayan admitted the evidence covered by said formal offer and the prosecution was

considered to have rested its case. On 14 January 1986, Abelardo filed a Motion for Separate Trial contending

that the prosecution already closed its evidence and that his defense is separate and distinct from the other

accused, he having been charged only as accessory. The motion was granted in an Order dated 17 January

1986. Thereafter, Abelardo commenced the presentation of his evidence. On 8 August 1986, Abelardo filed

his Formal Offer of Exhibits. On 14 August 1986, Abelardo filed his Memorandum praying that judgment be

rendered acquitting him of the offense charged. In a Resolution dated 26 August 1986, the Sandiganbayan,

through Presiding Justice Francis E. Garchitorena (then newly appointed after the EDSA revolution), admitted

all the exhibits covered by said Formal Offer of Exhibits at the same time, ordering the prosecution to file its

Reply Memorandum, thereafter the case was deemed submitted for decision. On 26 September 1986, the

prosecution filed its Reply Memorandum. Abelardo also filed his Reply Memorandum on 29 September 1986

praying that judgment be rendered acquitting him of the offense charged. In a Resolution dated 8 October

1986 copy of which was received by Abelardo on 15 October 1986, the Sandiganbayan deferred the decision

of the case regarding Abelardo until after the submission of the case for decision with respect to the other

accused. Abelardo filed his Motion for Reconsideration on 16 October 1986, but the Sandiganbayan in a

Resolution dated 16 December 1986 and promulgated on 6 January 1987 denied the same. The case was

submitted for decision on 20 June 1990. More than 10 years after the case was submitted for decision, the

Sandiganbayan has not rendered the Decision. On 15 August 2000, Abelardo filed his Motion to Resolve. This

was followed by Reiterative Motion for Early Resolution filed on 21 September 2000. Abelardo filed a

petition for mandamus with the Supreme Court

Issue: Whether the dismissal of Abelardo’s case is warranted by the guarantee on speedy trial or speedy

disposition of the case.

Held: Under Section 6 of PD 1606 amending PD 1486, the Sandiganbayan has only 90 days to decide a case

from the time it is deemed submitted for decision. Considering that the subject criminal case was submitted

for decision as early as 20 June 1990, it is obvious that the Sandiganbayan has failed to decide the case within

the period prescribed by law. Even if the Court was to consider the period provided under Section 15(1),

Article III of the 1987 Constitution, which is 12 months from the submission of the case for decision, the

Sandiganbayan would still have miserably failed to perform its mandated duty to render a decision on the case

within the period prescribed by law. Clearly then, the decision in this case is long overdue, and the period to

decide the case under the law has long expired. Even more important than the above periods within which the

decision should have been rendered is the right against an unreasonable delay in the disposition of one's case

before any judicial, quasi-judicial or administrative body. This constitutionally guaranteed right finds greater

significance in a criminal case before a court of justice, where any delay in disposition may result in a denial

of justice for the accused altogether. Indeed, the aphorism "justice delayed is justice denied" is by no means a

trivial or meaningless concept that can be taken for granted by those who are tasked with the dispensation of

justice. Indubitably, there has been a transgression of Abelardo's right to a speedy disposition of his case due

to inaction on the part of the Sandiganbayan. Neither that court nor the special prosecutor contradicted his

allegation of a ten-year delay in the disposition of his case. The special prosecutor in its Comment9 even

openly admitted the date when the case had been deemed submitted for decision (i.e. 20 June 1990), as well

as Sandiganbayan's failure to act on it despite Abelardo's several Motions to resolve the case. It has been held

that a breach of the right of the accused to the speedy disposition of a case may have consequential effects,

but it is not enough that there be some procrastination in the proceedings. In order to justify the dismissal of a

criminal case, it must be established that the proceedings have unquestionably been marred by vexatious,

capricious and oppressive delays. Herein, the failure of the Sandiganbayan to decide the case even after the

lapse of more than 10 years after it was submitted for decision involves more than just a mere procrastination

in the proceedings. From the explanation given by the Sandiganbayan, it appears that the case was kept in idle

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 9 )

Narratives (Berne Guerrero)

slumber, allegedly due to reorganizations in the divisions and the lack of logistics and facilities for case

records. Had it not been for the filing of the Petition for Mandamus, Abelardo would not have seen any

development in his case, much less the eventual disposition thereof. The case remains unresolved up to now,

with only the Sandiganbayan's assurance that at this time "work is being done on the case for the preparation

and finalization of the decision." Hence, the dismissal of the criminal case against Abelardo for violation of

his right to a speedy disposition of his case is justified by the following circumstances: (1) the 10-year delay

in the resolution of the case is inordinately long; (2) Abelardo has suffered vexation and oppression by reason

of this long delay; (3) he did not sleep on his right and has in fact consistently asserted it, (4) he has not

contributed in any manner to the long delay in the resolution of his case, (5) he did not employ any procedural

dilatory strategies during the trial or raised on appeal or certiorari any issue to delay the case, (6) the

Sandiganbayan did not give any valid reason to justify the inordinate delay and even admitted that the case

was one of those that got "buried" during its reorganization, and (7) Abelardo was merely charged as an

accessory after the fact. For too long, Abelardo has suffered in agonizing anticipation while awaiting the

ultimate resolution of his case. The inordinate and unreasonable delay is completely attributable to the

Sandiganbayan. No fault whatsoever can be ascribed to Abelardo or his lawyer. It is now time to enforce his

constitutional right to speedy disposition and to grant him speedy justice.

Constitutional Law II, 2005 ( 10 )