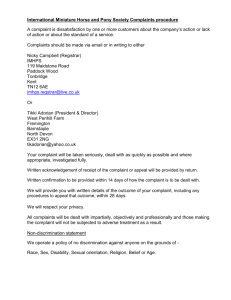

Client care: communication and service

advertisement