Profitability of Pay'what'you'like Pricing

advertisement

Pro…tability of Pay-what-you-like Pricing

Jose M. Fernandez and Babu Nahata

Department of Economics, College of Business

University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292.

emails jmfern02@louisville.edu; nahata@louisville.edu

1

Pro…tability of Pay-what-you-like Pricing

In this paper, we analyze a pricing strategy where consumers choose their own price

including zero. Our analysis shows that in this pay-what-you-like pricing strategy even

though consumers have an option to free-ride, not all will free-ride and some pay a positive

price. Even more surprising, we show that, under low marginal cost and for a low demand

elasticity range, pay-what-you-like pricing can achieve higher pro…ts for the seller compared

to uniform pricing. When price setting is costly and price discrimination is not feasible,

the pay-what-you-like option can serve as an alternative method to practice a form of price

discrimination that is similar to …rst-degree, but without incurring the cost associated with

identifying consumer types.

Keywords: pay-what-you-like pricing; price discrimination; microeconomics

1

Introduction

Pay-what-you-like pricing (PWYL) allows consumers to choose their own price, including

zero, and the …rm accepts whatever price is paid for a product or service. Although unorthodox, this form of pricing has existed for quite some time (e.g., village doctors and priests).

It has recently gained more attention in the popular press after the British band Radiohead

o¤ered their album In Rainbows to consumers on a pay-what-you-like basis in 2007. Between

October 1-29, 2007, 1.2 million people worldwide visited the website and among those who

downloaded the album, 38 percent worldwide and 40 percent in the U.S., willingly paid.

Free-riders were as prevalent in the U.S. as in the rest of the world, but in the U.S. a paying

customer paid $8.05 compared to $4.64 paid by his international counterpart.1 The success

of the album In Rainbows encouraged other …rms to o¤er their products using this form of

pricing. For example, the publisher of Paste magazine also adopted the same pricing policy

1

See http://www.inrainbows.com; and http://comscore.com/press/release.asp?press=1883; and the

Wall Street Journal, October 3, 2007, p.C14. The band also included a $2.00 transaction fee.

2

and subscribers can pay what they like for a year’s subscription to the magazine. Today,

we observe this pricing strategy among musicians, co¤ee houses, restaurants, theatres, and

magazines, but the economic rationale for its use compared to more traditional forms of

pricing has mostly remained unexplored.

The two most relevant questions for both theoretical and empirical analyses related to

PWYL pricing are: (1) what motivates consumers to pay when they have an option to

free-ride?2 and; (2) recognizing that the PWYL option may possibly result in losses, what

motivates the seller to o¤er such a pricing option?3 We provide some answers to both these

questions based on a theoretical economic model supported by real life anecdotes.

In the economics literature, such pricing strategies are analyzed as problems of multidimensional screening where information about willingness to pay is asymmetric (Rochet and

Stole 2003). From screening considerations, PWYL pricing and bu¤et pricing (or ‡at-fee

pricing) represent the two polar extremes. Under PWYL, the buyer decides how much to

pay for a given quantity. The opposite is the case with bu¤et pricing, where the buyer decides how much to consume for a given …xed fee (Nahata et al. 1999) . Under bu¤et pricing,

in spite of consumers having an option of unlimited consumption, they consume only a …nite

amount. Similarly, under PWYL pricing, even with a free-ride option, not all buyers select

to free-ride, as was the case with the Radiohead o¤er. Although not based on the traditional

pro…t-maximization assumption, both types of pricing strategies can generate higher pro…ts

than commonly used pricing strategies based on pro…t maximization. These strategies rely

on consumer self selection. Consumers freely self-select the quantity consumed in bu¤et

2

On CNN’s American Morning, John Roberts asked the question to the owner of the Java Street Cafe

in Kettering Ohio, who uses PWYL pricing: what prevents a customer to either free ride or pay a very

low price? The owner responded, “...When someone’s at the counter and you say, you get to pay what

you think is fair, very few people are going to take advantage of that situation.” (CNN March 17, 2009,

http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/03/017/lippert.quanda/#cnnSTCText

3

Wall Street Journal (August 28, 2007, p. B8) reports that the motivation for the owner of Terra

Bite Lounge in Kirkland, Washington for doing away with set prices was that PWYL pricing can be both

pro…table and charitable way of doing business. Further, “marketing buzz such a scheme generates can help

stand out from the pack.”

3

pricing and the payment under PWYL pricing.

Historically, pay-what-you-like pricing has existed for certain types of services. For example, in most Indian villages, the village priest accepts whatever the host pays for many

ceremonies he performs such as naming a newborn, performing a marriage, or other religious

services. This tradition still continues. Doctors in rural India are still paid based on how

much a patient can a¤ord. In the United States, it is common place to observe church parishioners practicing PWYL pricing when providing contributions (donations) to the church in

support of the services/programs o¤ered by the church.4

In 2005, the New Yorker magazine reported that in the Village, a quite popular place for

both the visitors and the residents of New York City, a restaurant named Babu used a menu

without any price. After …nishing their meals consumers paid what they liked.5 The owner

found that most consumers did pay, and some even paid considerably more than what the

owner expected.6 There were also a few cases of free-riders. Eventually, the owner did switch

to a menu with listed prices. On the other hand, since 1979, a small (maximum capacity

of about 10 people) and exclusive Japanese restaurant, Mon Cheri, in an expensive area of

Fukuoka City, Japan, has consistently maintained the PWYL pricing for dinners. The small

and intimate environment of this restaurant together with personal interactions could be the

reasons for this sustained use of PWYL pricing.

Kim, Natter and Spann (2009) o¤er the …rst empirical study of PWYL pricing. Based

on three …eld experiments in Germany, the authors report several interesting …ndings about

consumers’responses to this form of pricing. In this study, three di¤erent sellers o¤ered three

di¤erent products for sale and consumers could choose any price they like to pay, including

4

Some donations are made out of guilt. Gruber (2003) shows that religious attendance and religious

givings are substitutes.

5

See Rebecca Mead, the New Yorker, March 21, 2005, for other details. Cabral (2000, p.185) also

mentions a restaurant in London that does not list prices in the menu; and each customer is asked to pay

what he or she thinks the meal was worth. Recently, many cafes and restaurant in the US have also adopted

this practice.

6

Lynn (1990) argues that some customers in a restaurant pay more to avoid the impression of looking

cheap.

4

zero. Although there was a wide distribution of payments made by consumers, surprisingly

no one did free-ride and all consumers paid a positive price. Based on the study, the authors

conclude that a consumer’s willingness to pay depends mainly on two factors: (i) an internal

reference price for each consumer; and (ii) a proportion of consumer surplus a consumer is

willing to share with the seller. Our analysis formally incorporates these two factors.

Except for the above mentioned …eld study, we are not aware of any other empirical

or theoretical analyses related to this particular form of pricing, although there is a vast

body of literature on public goods. The striking similarity between the PWYL o¤er and

the private provision of a public good is that in both cases no one can be excluded from

consuming the good. In spite of this similarity, the two situations are very di¤erent. First, a

public good will not be provided by the market unless there is some mechanism to pay for its

provision. Certainly, this is not the case with the goods that are being o¤ered using PWYL

option. Firms have an incentive to o¤er the good under both the PWYL option or use some

other form of pricing. Second, the choice of PWYL is endogenous as the …rm compares

the expected pro…ts with some other pricing strategy that is based on a pro…t-maximizing

solution, for example, uniform pricing. No such pro…t incentive exists in the provision of a

public goods.

Kim et al. (2009) present several behavioral factors that may dissuade consumers from

free-riding. Based on the literature from psychology, marketing, and experimental economics,

they posit four factors a¤ecting consumers’decision to pay. The most common reason given

in favor of paying, as opposed to free riding, is social-norms, which has also been considered as

one of the reasons for tipping.7 The other factors that may dissuade free riding are: avoiding

the appearance of looking cheap; fairness and reciprocity; and altruism.8 Further, based on

the estimation results, the authors conclude that the …nal prices paid were in‡uenced by (a)

7

Tipping for services (e.g, taxi, waiter etc.) is not considered a social norm in Japan and hence tipping

is almost non-existent in Japan. See also Conlin et al. (2003).

8

Kim, Natter and Spann (2009) survey the literature quite extensively. To conserve space, we avoid the

duplication and urge the interested readers to refer to their paper and the references included.

5

fairness, (b) satisfaction, (c) market price awareness, and (d) net income (p. 53).

Our main contribution is to derive the conditions under which PWYL pricing can achieve

higher pro…ts than a pro…t-maximizing uniform price. We derive these conditions under two

di¤erent sets of assumptions about consumer behavior: consumer guilt and repeat buyers.

To the best of our knowledge, no such criteria for pro…t comparison has been put forward

for PWYL pricing.9 In addition, we also explore how PWYL pricing becomes an attractive

alternative compared to other pricing strategies when price setting is quite costly. Wernerfelt (2008) explains the practice of “class pricing” where many products within a “class”

are priced the same (e.g., a dollar store) when costs of setting price of each good is quite

signi…cant.

Our conditions (Proposition 2) show that when consumers have some guilt from paying

a price lower than some reference price; and the marginal cost is either zero or very small

and the price elasticity of demand evaluated at the pro…t maximizing uniform (reference)

price is within a narrow range (between one and two) PWYL can be more pro…table than

uniform pricing.

The rationale behind this result is simple and appealing. Under a uniform price, the

maximum level of pro…ts occurs when the marginal cost of production is zero. At this price,

the elasticity of demand equals its lower limit of one. Further, the linear demand case yields

the special result that both the consumer surplus and the deadweight loss are equal to each

other and each is one-half of the maximum pro…t. This signi…cant amount of deadweight loss

cannot be captured as pro…ts using commonly observed and analyzed linear or nonlinear

pricing strategies, especially in the presence of large degree of consumer heterogeneity. However, PWYL pricing creates an opportunity for eliminating the deadweight loss by sharing

it between the consumers and the seller, thus making it pro…table for the seller. At the

9

As far as pro…tability of bu¤et pricing is concerned, several papers have argued that when the savings

from the transaction cost (e.g., cost of monitoring the consumption etc.) can o¤est the cost of extra production then bu¤et pricing can be more pro…table than a pro…t-maximizing two-part tari¤. More formally,

the criterion proposed states that if the total cost under two-part tari¤ exceeds the net total cost (total

production cost less the savings from transaction cost) then bu¤et pricing is more pro…table than a two-part

tari¤ (Proposition 1 in Nahata et al. 1999).

6

same time elimination of deadweight loss increases the consumer surplus for the existing

consumers and creates surplus for those who were previously excluded from the market. For

consumers who bought at the uniform price, the PWYL option (which allows them to pay

even lower than the uniform price) are unambiguously better o¤ because their surplus will

increase. But, because of loss in pro…ts from the existing consumers, the seller becomes

worse o¤.

On the other hand, the PYWL option opens up the market by now including those

consumers who were previously excluded from the market under the uniform price. This

opening up of the market creates an opportunity for both the seller and entrants to share

the deadweight loss. These new entrants gain surplus by paying a price lower than their

willingness to pay. The seller gains additional pro…ts from payments made in excess of the

marginal cost. Compared to uniform pricing, the seller’s pro…t will be higher under PWYL

if the pro…t earned from the elimination of the deadweight loss is large enough to o¤-set

the revenue lost from existing consumers. The logic is similar under positive but still very

small marginal cost (see Fig. 1). Thus, whenever PYWL pricing is pro…table, it is also

Pareto improving. It is socially optimal when the marginal cost is zero, but under positive

marginal cost because the total consumption exceeds the social optimal, it is not the …rst

best outcome.

If we ignore guilt, but instead consider that consumers are loyal to the …rm, then we

can show that under su¢ ciently low marginal cost and a su¢ ciently high proportion of loyal

customers PWYL pricing becomes a viable and pro…table alternative to uniform pricing.

Generally, in a small community local …rm is frequented by many loyal customers and when

in some cases the proportion of loyal customers is large enough, PWYL may become more

pro…table.

The PWYL option also allows …rms to practice price discrimination when it is typically

considered infeasible. For example, when consumer heterogeneity is large and …rms cannot

separately identify consumer types (or doing so is very costly), then uniform pricing becomes

7

the most appealing pricing option because screening consumers to practice either second- or

third-degree price discrimination is infeasible. But, under uniform pricing the deadweight

loss remains signi…cantly high compared to either second or third degree price discrimination. Since PWYL pricing cannot exclude consumers based on price, this option makes the

potential level of market participation the highest. Further, since consumers choose how

much to pay for the good or service themselves, the seller does not have to incur any cost

associated with …nding potentially pro…table and at the same time easily implementable

screening mechanism. Lastly, the payment schedules of these consumers mimics an indirect

version of …rst-degree price discrimination.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. § 2 presents a model based on the assumption

that consumers derive disutility from paying a price lower than some reference price and

compares pro…ts under PWYL with uniform pricing. We extend the model by incorporating

the cost of price setting. In § 3, we present another model based on repeated interactions

between consumers and the …rm and obtain similar results. § 4 contains discussions and

summarizes the results.

2

Model

In this section, we present a game theoretical model considering “guilt” or “fairness”

in a consumer’s utility function and demonstrate how guilt, resulting from paying below a

known reference price, can make consumers pay even in the presence of a free-ride option

(Proposition 1). Our Proposition 2 states the necessary conditions for PWYL pricing to

generate higher expected pro…ts than uniform pricing. We extend the model by incorporating

the costs of price setting. When price setting is costly, there is an incentive to use pay-whatyou like pricing when the market is small and/or pricing cost is large (Proposition 3).

8

2.1

Model with Guilt

Traditional economic models view consumers as self-interested agents.

Under PWYL

pricing, these consumers would select a price of zero ignoring any cost these actions could

impose on others. Yet, there is substantial evidence from the behavioral economics literature

suggesting that consumers do care for the welfare of others (Thaler 1992; Camerer 2003) and

of local …rms (Duncan and Olshavsky 1982). For this reason, we consider a model incorporating consumer guilt. Let there be N consumers in a market for a highly di¤erentiated

good. Consumer i’s utility function is

Ui =

vi

vi

pi

pi

(pu

(vi

pi )2 vi pu

pi )2 vi < pu

(1)

where vi is consumer i’s private value for the product, pi is the price paid by consumer i,

pu is some reference price which is assumed to be equal to the uniform price, and the “loss”

parameter

price.

captures the degree of guilt associated with paying a price below the uniform

Consumers’ values are assumed to be distributed uniformly and have a support

vi 2 [0; v]. Further, let G(v) =

v

v

be the cumulative density function over consumer values.

In our formulation, the …rst term in (1) captures a consumer’s surplus. The second term

internalizes the loss from guilt and also highlights the importance of the reference price.

In our speci…cation of consumer’s utility, the loss parameter is identical for all consumers

(we relax this assumption later) and has a support

self-interested when

2 [0; 1): A consumer is said to be

= 0: A consumer experiences guilt when

> 0; and she pays an

amount less than the uniform price (or the private value), pi < min[vi ; pu ]. The cost of guilt

is proportional to the additional amount of surplus received from paying below the uniform

price.

In the case of consumers who are previously excluded from the market, this cost

is proportional to their gross surplus as they would have received a surplus of zero under

the prevailing uniform price. Note, a consumer will never pay an amount greater than the

uniform price (or their private value). If vi

pu , then a consumer can always purchase the

9

product without guilt at the uniform price. If vi < pu ; then the consumer’s contribution

cannot be greater than their willingness to pay, vi :

2.2

Structure of the Game

The game is played in two stages. First, the …rm chooses a pricing strategy: uniform

pricing or PWYL pricing.

Second, consumers observe the pricing strategy and choose

to participate. Under uniform pricing, all consumers with private values greater than the

uniform price enter into the market and pay the uniform price, vi

pu . Under PWYL pricing

all consumers enter into the market and choose a price that maximizes their utility.

We

assume consumers make payment decisions independent of other consumers. They neither

observe the private values of other consumers nor the …rm’s cost of production. The reason

for this structure is that, in reality, consumers do not formally or informally cooperate with

other consumers when making a purchase. Consumers simply observe the pricing options

and make choices that maximize their utility. We seek a subgame-perfect equilibrium in pure

strategies under asymmetric information: the …rm’s payo¤ is taken over the expectation of

consumers’ strategies.

The equilibrium of the game is found using backward induction.

The …rm solves the consumer’s problem under both pricing strategies and then chooses the

pricing strategy that yields the highest expected pro…ts.

2.3

Consumer Behavior

Consumer behavior under uniform pricing is de…ned over a discrete strategy space. Consumers choose either to participate or remain out of the market.

when vi

Consumers participate

pu and pay pi = pu : Regardless of the value of ; consumers do not experience

guilt under uniform pricing as the reference price is equal to the uniform price. It is important to highlight the presence of consumers who have positive value for the good vi > 0,

but are locked out of the market because vi < pu : If the …rm could price discriminate, then

pro…ts would increase by including consumers whose values are greater than the marginal

10

cost, vi > c:

Consumer behavior under PWYL pricing is de…ned in a continuous strategy space. All

consumers participate in the market, but each consumer pays a di¤erent price, pi .

The

optimal contribution amount maximizes utility conditional on guilt. A consumer’s marginal

utility with respect to price, pi ; is given by the following equation.

@U

=

@pi

1

2 (pi

(2)

min [pu ; vi ]) = 0.

The optimal price, pi ; which maximizes utility, is

pi =

pu

vi

1

2

1

2

vi pu

vi < p u

(3)

where pi is strictly increasing with respect to the guilt parameter, :

From Equation (3) we state the following proposition.

Proposition 1.

In the presence of guilt, pay-what-you-like pricing results in free riding

behavior or pi = 0 8 i when

1

2pu

= . Consumers with private values vi 2 0; 21

always

free-ride:

Remark. The cuto¤ value

represents the minimum level of guilt required in order to

make positive contributions under PWYL pricing. In the presence of guilt, there still exists

an incentive to free-ride. The participation constraint requires Ui

0. Given the functional

form of consumer’s utility function, free-riders have positive utility when their private values

are represented by vi 2 0; 1 : Among these consumers, those with vi <

1

2

and consumers with vi

1

2

will free-ride

are better o¤ making a small contribution in accordance with

Equation (3), but all consumers within this bound do participate as the minimum utility

gained from free riding is zero. A …rm can e¤ectively stop free riding by requiring a minimum

contribution equal to

1

2

.

11

2.4

Firm Behavior

The …rm chooses between two pricing strategies: uniform pricing or PWYL pricing.

Under uniform pricing, the …rm chooses a price, pu ; that maximizes pro…t. The expected

pro…t function, E [

u] ;

is

E[

u]

= maxN [1

G (pu )] (pu

pu

c)

(4)

F

where c is the marginal cost of production and F is the …xed cost.

The expressions for

equilibrium price, quantity, and pro…ts under uniform pricing are well known and are given

below.

pu =

v+c

8 i; q = N

2

v

c

2v

; and

u

=

N

(v

4v

c)2

F.

(5)

Note, the …rm’s strategy space is continuous as it chooses a single price on the support

pu 2 R+ . In the case of PWYL pricing, the …rm’s decision is reduced to a discrete choice

of entry or exit. The roles of the …rm and the consumer are reversed under PWYL pricing.

Furthermore, the …rm chooses to relinquish its property rights for the good instead of selling

those rights away.

The expected pro…t function under PWYL pricing has the following form

E[

where revenue, R =

N

P

pwyl ]

= E [R]

cN

(6)

F

pi ; remains uncertain and total costs are pre-determined as no con-

i=1

sumer can be turned away.

Having previously de…ned consumer behavior under PWYL

pricing. The expected total revenue is:

2

6

6

E [R] = N 6[1

4|

G (pu )] pu

{z

vi pu

1

2

}

+ G (pu )

|

G

1

2

Z

pu

1

2

vi

{z

vi <pu

12

1

2

G0 (vi )

G(pu ) G( 21

3

7

7

dvi .7 (7)

)

5

}

The expected revenue function consists of two parts. The …rst term measures the revenue

obtained from consumers who would have otherwise participated in the market under uniform

pricing. Note that these consumers have di¤erent private values for the good, but each makes

the same contribution.

Furthermore, the amount paid cannot exceed the uniform price

implying that PWYL pricing can only increase welfare for these consumers. The uniform

price creates a lower bound on the utility function as no consumer can be made worse o¤

under PWYL pricing compared to uniform pricing.

The second term in (7) accounts for the revenue obtained from those consumers who

would not have been served with uniform pricing. Only consumers with private values in

excess of

1

2

will contribute as the rest have an incentive to free-ride. Payments made by

these individuals can be viewed as an indirect form of …rst degree price discrimination. Each

consumer pays an amount which is a monotonic transformation of their true private values.

Therefore, PWYL pricing allows a …rm to practice …rst degree price discrimination without

the knowledge of consumers’ true willingness to pay. However, such pricing could become

more costly as no consumer can be turned away. The expected revenue function simpli…es

to

E [R] = N

h

(4v

2pu

1)(2pu

8v

2

1)

i

where revenues are increasing both with respect to the uniform price,

and guilt,

2.5

@E[R]

@

=

N

2

1

1

2v

(8)

@E[R]

@pu

=N 1

pu

v

0;

0.

Pro…ts Comparison

In this section, we derive conditions to compare pro…ts under uniform and PWYL pricing

in terms of three parameters namely the guilt parameter ; valuation v; and the marginal

cost of production c such that PWYL pro…ts exceed pro…ts under uniform pricing. PWYL

pro…ts dominate uniform pro…ts,

pwyl

>

u;

when the following inequality is satis…ed

13

N

(4v

2pu

1) (2pu

1)

2

8v

c

F >

N

(v

4v

c)2

F.

(9)

In order for this inequality to hold, the lower and the upper bounds on the guilt parameter

can be founds as:

2v

p

1

2c2 +4cv+6v 2 8vpu +4p2u

<

< 1:

(10)

Derivation is included in appendix. Substituting for the uniform price, pu =

bound on

v+c

,

2

the above

simpli…es to the following inequality

2v

In essence, the bound on

p

1

3c2 +2cv+3v 2

<

< 1:

(11)

indicates that the level of guilt must increase with marginal

cost for PWYL pricing to be more pro…table than uniform pricing. For this reason, PWYL

pricing is less likely to be observed for products with a high marginal cost of production.

The simple intuition is that as the marginal cost increases, the marginal pro…t loss from

free-riders must also increase. Therefore the number of free-riders must decrease in order to

compensate for this pro…t loss. Consumers with private values vi 2 0; 21

always free-ride.

1

2

c: Therefore, an

The costs that free-riders impose on the …rm are equal to N Pr vi <

increase in the guilt parameter ( ) is required to reduce the number of free-riders and o¤set

the increase in marginal cost. But, when the uniform price increases, the required level of

guilt needed for PWYL pricing to be more pro…table decreases. The uniform price (reference

price) represents the opportunity cost of consumer in participating in the pay-what-you-like

option.

A higher uniform price has two e¤ects on consumers: (1) the opportunity cost

of purchasing the product “guilt free” increases and; (2) at a higher uniform price more

consumers are excluded from the market. These two e¤ects encourage the use of the PWYL

in order to attract these consumers.

In Proposition 2, we state the necessary conditions for PWYL pricing to be more profitable than uniform pricing.

14

Proposition 2. If pro…ts under pay-what-you-like pricing were to exceed the pro…ts under

uniform pricing then: (i) the marginal cost c <

v

3

or; (ii) the price elasticity of demand at

the pro…t-maximizing uniform price in equilibrium must be less than 2 .

PROOF.

From the bounds on

(Equation. 11), it is easy to see that as the marginal cost ap-

proaches v3 , the minimum level of guilt for PWYL pricing to be more pro…table approaches

in…nity c =

v

3

=)

will be satis…ed only when c < v3 : The

= 1 . The upperbound on

second part of the proposition follows from the Lerner’s Index which at the equilibrium

pro…t-maximizing uniform price can be written as

1

=

pu c

,

pu

number) is the price elasticity of demand. Noting that pu =

the price elasticity of demand

where

v+c

2

(de…ned as a positive

and c < v3 , it follows that

< 2:

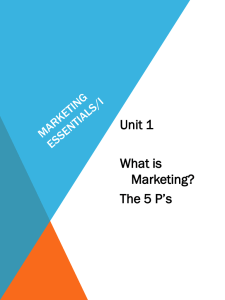

The results from this section can be explained by Figure 1. Pro…t under uniform pricing

is the sum of Area I and Area II. Pro…t under pay-what-you-like pricing is Area II + Area

III - Area IV. Therefore, the di¤erence in pro…ts is Area III - Area I - Area IV. If the

marginal pro…t gained from the new entrants (Area III) is greater than the revenue lost from

the existing consumers (Area I) and the associated cost due to expanding the market (Area

IV), then PWYL pricing is more pro…table than uniform pricing. It is worth noting that (i)

as guilt increases (an increase in ); Areas I and IV decrease but Area II increases allowing

the …rm to capture more of the deadweight loss with an increase in consumer guilt; (ii)

as marginal cost approaches zero, c ! 0; PWYL pricing o¤ers the Pareto e¢ cient outcome

and there is no deadweight loss in equilibrium. This happens without incurring any cost for

expanding the market (Area IV disappears).

15

Figure 1: Comparing pro…t if Area III - Area I - Area IV >0, then

2.6

pwyl

>

u.

Costly Price Setting

Thus far we have assumed that setting a uniform price or the use of any other pricing

strategy is costless. However, an optimal price setting requires demand estimation which in

turn requires market research. According to IBISWORLD, the US market research industry

generated over $14 billion of revenue in 2009.10

The cost of pricing is very relevant in

particular for experience goods or for launching a new product. For example, an aspiring

musicians may have little or no information about their fans’willingness to pay, or the quality

of their own product. Suppose consumers’ values are uniformly distributed v ! U (0; a),

but a may take on only two values a 2 f1; 2g where Pr(a = 1) = :5 and Pr(a = 2) = :5: In

this case, the …rm is uncertain about both consumers’valuations for the good and whether

to serve high-demand consumers (a = 2) or low-demand (a = 1) consumers. Since it may

be quite costly to determine the optimal price given the uncertainty about consumer values

and the value of a, …rms may choose the less costly option of using PWYL pricing to

10

http://www.ibisworld.com/industry/default.aspx?indid=1442

16

reduce uncertainty. Thus a potential source of savings associated with PWYL pricing is the

reduction in the cost related to setting a price because now consumers, and not the …rm,

bare the cost of pricing.

We demonstrate this cost savings by allowing the …xed cost to vary between the two

pricing options. In Equation (9) let the …xed cost associated with PWYL pricing be F =

, where

F

is the cost of pricing . As in the previous section, we solve for the minimum

level of guilt such that

pwyl

>

u

as a function of the marginal cost, consumer valuation

v; the market size N , and the cost of pricing : Incorporating the cost of pricing reduces

the minimum level of guilt for pro…tability and increases the likelihood of the use of PWYL

pricing. The lower bound on

is given by

>

2v

p

1

3c2 +2cv+3v 2

8v

N

.

(12)

Proposition 3. When price setting is costly then there exists an incentive to use paywhat-you like pricing when the market is small (low N) and/or pricing cost are large (high

q

2

< 1.11

). The upper bound on marginal cost is c < 3 v(vNN+6 ) v3 = c for

Proof. See appendix.

This result provides insight into why some of the …rms mentioned earlier use PWYL

pricing. The exclusive restaurant in Japan is quite small (low N) thereby amplifying the

cost savings associated with price setting. On the other hand, in the case of Radiohead,

both consumer heterogeneity and the market size are quite large. Yet, PWYL pricing is

adopted because both the costs of market research and the screening cost for price setting

are signi…cant considering that music is an experience good (high ).

These same cost savings could also a¤ect entry.

market only if the expected pro…ts are positive.

On the margin, a …rm enters into a

One can argue that a …rm that would

not have entered the market because a uniform price would have resulted in negative pro…ts

11

Note that

@c

@

=2

q

v

N (N v+6 )

> 0 and

@c

@N

=

N

q

17

v

N (N v+6 )

< 0.

(

u

< 0) may enter under PWYL pricing as the cost saving without market research may

be signi…cant enough to result in positive pro…ts (

pwyl

> 0).

Further, PWYL pricing is an experiment for “learning.”A …rm could learn the demand

for the product by observing the sequence of consumer payments. Recall that each payment

is a monotonic function of the consumer’s true value. The …rm can deduce a consumer’s true

value from her payment or use a Bayesian method to update beliefs on consumer’s willingness

to pay. For this reason some …rms may abandon the PWYL option as they become more

established and have learned the demand for their product. This may have been the case

with the restaurant Babu in the Village that subsequently switched to a uniform price after

initially practicing PWYL pricing.

Our results and arguments are similar to those made for class pricing, which also attempts

to reduce costs associated with pricing. Wernerfelt (2008) motivates the use of “class pricing”

as a method to reduce the cost associated with selecting individual prices for similar products

(i.e., one tuition fee for a variety of university classes). Class pricing is preferred in markets

with a small number of buyers, a large number of product versions, and a small variance in

costs. Class pricing and PWYL pricing share some of the same characteristics in reducing

the cost associated with pricing within small markets (low N), but di¤er with respect to

the ex ante di¤erence in demand.

PWYL pricing is preferred when there is a great deal

of consumer heterogeneity where as class pricing is preferred when there is little ex ante

di¤erence in demand between versions.

So far, we have assumed that every consumer has the same level of guilt or sense of

fairness, : Dubner and Levitt (2004) show consumers have varying beliefs about guilt

and/or fairness. The article describes payment di¤erences between employees who purchase

bagels based on the honor system. In this case, high paid executives are less likely to pay

than lower paid employees within the same …rm. For this reason, we relax the assumption

of identical guilt among consumers. Instead assume Pr ( = 0) = 1

and Pr

=b = :

Adding uncertainty to the guilt parameter unambiguously decreases pro…t under pay-what-

18

you-like pricing, but does not a¤ect pro…t under uniform pricing.

Expected pro…t under

pay-what-you-like pricing is

E

h

2

i

( )pwyl = N 4

4vb

2pub

1

2

8vb

2pub

1

3

c5

F

(13)

where the …rm still serves the whole market, but revenues fall as the percentage of “guilt free

consumers” increases. The minimum level guilt required for pay-what-you like pricing to

be pro…table is b >

2v

r

1

2N (v+c)2

8v +N (v c)2

N

where

@b

@

< 0 for

2 (0; 1]: The minimum level

of guilt must rise to o¤-set both the cost associated with expanding the market and the

presence of two free-rider types: (1) strategic free-riders who have vi <

free-riders caused by

3

1

2

; and (2) random

who are located over the entire distribution of private values, vi :

Model of Loyal Consumers

In addition to the earlier model based on guilt, we now present a model that considers

repeated interactions between the consumer and the …rm. In this model payments are made

as a result of a dynamic game played between the …rm and its loyal consumers. Loyal

(repeat) customers have an incentive to support PWYL pricing as this pricing mechanism

o¤ers a higher level of life time consumer surplus than paying uniform prices in every period.

Although the underlying assumptions for these two models are very di¤erent, both models

predict a similar payment behavior on the part of consumers.

We derive the necessary

conditions under which PWYL pricing gives lower expected pro…ts than uniform pricing.

Let there be N in…nitely lived consumers with a single period utility function given

as: Ui = vi

pi : Suppose the proportion of repeat (loyal) buyers is

repeat buyer has a discount factor

2 [0; 1] and each

2 [0; 1): A consumer maximizes their lifetime utility by

selecting a contribution sequence. If the …rm chooses a uniform price, then each consumers

19

has a lifetime utility

Vu (vi ; ) =

vi

1

pu

(14)

where a consumer chooses to participate if vi > pu : The consumer’s value function under

pay-what-you-like pricing for repeat buyers is

V (vi ; ) =

vi pi

1

s.t: E [

pwyl ]

The above expression simpli…es to V (vi ; 0) = vi

E[

u] .

(15)

pi for non-repeat consumers ( = 0).

Therefore, a non-repeat consumer always has an incentive to free-ride under the PWYL

option.

Consider the following game.

In the …rst stage, the …rm chooses a particular pricing

strategy: uniform or PWYL. In the second stage, consumers choose to participate and, in

the case of PWYL pricing, choose how much to pay. The game is repeated subject to the

…rm earning positive pro…ts.

If the …rm’s pro…t under PWYL pricing are less than the

pro…t under uniform pricing, then the …rm will punish consumers by choosing the uniform

price in all future periods. Given the setup of the game, consumers will choose a payment

schedule such that the …rm is indi¤erent between uniform and PWYL pricing. Consumers

capture the entire surplus in this game, but there exists an in…nite number of possible

payment schedules that satisfy the constraint E [

pwyl ]

E[

u]

in equilibrium.12 Further,

the payment schedule must satisfy the following consumer participation constraint.

vi pi

1

vi + min

(vi

1

pu )

;0 .

(16)

Consumers will not choose to free ride under PWYL pricing if their lifetime utility when

committing to a positive price exceeds lifetime utility where consumers free ride in the …rst

12

For example, two potential equilibria result in either dividing the net surplus (after payment) among

all consumers evenly or giving all the net surplus to one consumer. At that point, no consumer can gain

additional surplus without triggering the …rm to use uniform price, thereby making everyone else worse o¤.

20

period and pay the uniform price in all subsequent periods. The participation constraint

can be simpli…ed to

pi =

min [vi ; pu ]

(17)

pi

where the maximum contribution amount, pi ; leaves the consumer indi¤erent between freeriding and committing to a positive price.

The maximum amount a consumer is willing to pay is strictly less than her private value,

but is proportional to min [vi ; pu ].

As the discount factor decreases consumers become

less patient and the incentive to free-ride increases. Since the marginal bene…t of future

consumption decreases with the discount factor, consumers are less willing to cooperate with

the …rm over the long-run. If we consider the discount factor to represent the probability

of a repeat visit in the future, then contributions are increasing as consumers become more

loyal. This theoretical result is supported by empirical evidence in the tipping literature.

Conlin, Lynn, and O’Donoghue (2003) …nd that repeat consumers, on average, provide larger

tips than one-time consumers.

Now we can obtain a necessary condition which when satis…ed makes pay-what-you-like

pricing always less pro…table than uniform pricing. First, we …nd the expected maximum

level of revenue that can be generated in the absence of free riding. From Equation (17) ; if

consumers have private values vi > pu ; then the maximum contribution is pi = pu , otherwise

pi = vi : The expected revenue function is given in Equation (18) where the …rst term in

the brackets is the average payment made by consumers with private values vi > pu and the

second term is the average payment by all other consumers.

max E [R] =

N [1

G (pu )] pu + G (pu )

Z

0

=

N pu 1

pu

2v

.

pu

vi

g (vi )

dvi

G (pu )

(18)

Next, we compute expected pro…ts under both pricing strategies, then solve for the value

of the discount factor such that uniform pricing is strictly more pro…table than PWYL,

21

pwyl

<

u:

Proposition 4 states the conditions.

Proposition 4. Given the uniform price pu =

v+c

.

2

Pro…ts under uniform pricing are

higher than pro…ts under pay-what-you-like pricing when: (i)

<

2(v+c)

(3v c)

; or (ii)

v

3

< c; 8 ;

< 23 ; 8 and 8c:

or (iii)

Proof. See appendix.

The magnitude of marginal cost again becomes critically important for the adoption of

PWYL pricing. A su¢ ciently low marginal cost and a high proportion of loyal consumers

can make PWYL pricing a viable pro…table alternative to uniform pricing. The intuition is

supported by what is observed in real life. For example, PWYL pricing is not practiced by

…rms serving mainly tourists because the proportion of repeat buyers is very low. On the

other hand, PWYL pricing may turn out to be a pro…table strategy in small communities

where consumers have a preference for locally owned businesses (high

and/or high ).

Finally, incorporating pricing cost relaxes the restriction on the discount factor. As

stated in Equation 17, contributions are function of the discount factor. The …rm can accept

lower payments from consumers (due to lower

) when the loss in revenue is o¤-set by a

corresponding increase in the cost associated with pricing. The upper bound on the discount

factor

is given by13

<

2(v+c)2 =N

(3v c)(v+c)

(19)

where where =N is the average amount of savings per consumer Again, the likelihood of

PWYL pricing increases as the market size decreases (low N ) and/or pricing cost increase

(high ).

The savings resulting from forgoing the cost of pricing allows the …rm to use

PWYL pricing while accepting lower payments.

13

For derivation see appendix

22

4

Conclusions and Discussion

Our analysis provides a theoretical economic framework that incorporates both the seller

and consumers behavior under the pay-what-you-like option. The model shows why a …rm

may allow consumers to choose their own price and why consumers would choose to pay

even when they have the option to free ride. The more pro…table choice between PWYL

or uniform pricing for the …rm depends on consumers behavior. When consumers derive

disutility because of guilt from paying lower than the uniform price then a …rm can exploit

the presence of guilt to expand the market by o¤ering PWYL pricing. By doing so, the …rm

can generate higher pro…ts compared to uniform pricing when marginal cost is small relative

to consumers’valuations and the demand elasticity is low. Our result provides support for

the empirical …ndings of Kim et al. (2009) by demonstrating that in equilibrium not all

consumers free-ride as was observed in their …eld study and also in many other examples

mentioned.

We extend the model by explicitly including the cost of price setting and show that

PWYL pricing can provide a signi…cant source of savings when the cost of setting a price

is high due to market research or uncertainty. In small markets, the savings in setting price

can motivate the use of PWYL pricing and class pricing. These two strategies di¤er in the

ex-ante di¤erence in demand. Class pricing is preferred when ex-ante di¤erences in demand

are small, but PWYL pricing is better suited when there is more consumer heterogeneity.

We further show that even in the absence of any guilt, PWYL can also be a pro…table

strategy when consumers are loyal and there are repeated interactions between consumers

and the …rm. In this case, when the discount factor is high, the proportion of loyal consumers is greater than 2/3, and the marginal cost is low, PWYL pricing may be sustained

as an equilibrium. Under these conditions, consumers can maximize their lifetime utility by

providing a positive payment instead of facing a uniform price in every period and they will

choose a payment schedule such that the …rm is left indi¤erent between PWYL pricing and

uniform pricing. Further, the net-surplus gained by using PWYL pricing can be distributed

23

among all the consumers resulting in a Pareto improvement.

Our theoretical model o¤ers some reasons as to why this unorthodox form of pricing is

rarely observed.

First, this pricing strategy requires a very low marginal cost relative to

consumers’valuations. Second, the elasticity of demand at the pro…t maximizing uniform

price must be within a narrow range (between one and two). Third, unlike a market serving

mainly tourists, the market for this pricing option must contain a captive set of consumers

who are driven either by loyalty or guilt. For this reason, PWYL pricing is most likely to be

observed for experience goods with small market size. If either the good or the seller of the

good is not su¢ ciently di¤erentiated (e.g., art, music, etc.), then pay-what-you-like pricing

is not suited and the …rm should compete in prices with other …rms. But, if the product is

su¢ ciently di¤erentiated or consumer heterogeneity is high, then PWYL pricing facilitates

a voluntary segmentation based on consumers’self selection facilitating an indirect form of

…rst-degree price discrimination without incurring the cost such practice generally requires.

Willig (1978) shows that a uniform price that exceeds marginal cost is Pareto dominated

by a nonlinear outlay schedule. He constructs a particular schedule that is preferred to the

uniform price by all consumers and the seller. We extend this consumer by showing that

PWYL schedule which is not a nonlinear outlay schedule can also can be Pareto dominating

compared to uniform price. Although the set of nonlinear Pareto-superior schedules is much

bigger, a nonlinear outlay is not necessary for Pareto domination. Further, under the PWYL

option, Pareto domination occurs in spite of free riding by some consumers and the seller

not covering the marginal cost of all additional quantities consumed. This interesting result

is the novelty of our paper.

Finally, we o¤er some suggestions for the future direction of empirical research. Although

conclusions from both models …nd similar restrictions on marginal cost and derive consumers’

payments as monotonic transformations of their private value for the good, the underlying

assumptions on consumer behavior are quite di¤erent. Future empirical work should focus

on designing a method that can separately identify the reasons for consumer payments, guilt

24

or loyalty, and in particular, the relative weights consumers place on these two factors when

making payments.

Appendix. Proofs

Derivation of equation (11)

In the guilt model,

pwyl

u;

2pu

(4v

N

>

when the following inequality is satis…ed.

1) (2pu

1)

c

2

8v

F >

N

(v

4v

c)2

F

This equation can be simpli…ed to

(4v

2pu

1) (2pu

8v

1)

2

c>

(v

c)2

4v

as …xed cost and market size are the same in both settings. We next solve the inequality

with respect to the guilt parameter, : The solution is found using Mathematica.

roots are found for

@ 1

@c

:

1

=

2

=

2v

p

1

2c2 +4cv+6v 2 8vpu +4p2u

2v+

p

1

2c2 +4cv+6v 2 8vpu +4p2u

@ 1

@c

< 0: Note, the di¤erence between pro…ts pwyl

u is decreasing with

@ ( pwyl

u)

@

respect to marginal cost,

< 0 and increasing with respect to guilt, @pwyl > 0:

@c

where

> 0 and

Two

Therefore, the second root of the guilt parameter, 2 ; is internally inconsistent as it implies

@ ( pwyl

u)

> 0: We conclude 1 is the unique solution.

that

@c

Proof of Proposition 3

The proof to proposition 3 is similar to the derivation of Equation (11) : We modify

Equation (9) to re‡ect the cost of pricing

N

(4v

2pu

1) (2pu

8v

1)

2

25

c +

>

N

(v

4v

c)2

where …xed cost under PWYL pricing is F = F

: We next set the uniform price pu =

v+c

2

and solve the inequality with respect to the guilt parameter, : The solution is found using

Mathematica. Two roots are found for

where

@ 1

@c

> 0 and

the solution.

@ 1

@c

1

=

2

=

:

2v

p

1

3c2 +2cv+3v 2

8v

N

2v+

p

1

3c2 +2cv+3v 2

8v

N

< 0: As in the derivation of Equation (11) ; the root

1

is select as

The bound on marginal cost is found by solving the denominator of

1

for

zero. In this case, the upper bound on marginal cost for PWYL to be more pro…table is

2

c<

3

which simpli…es to c <

v

3

r

v (vN + 6 )

N

v

3

when the cost of pricing is zero,

= 0:

Proof of Proposition 4

If consumer’s private values vi > pu , then the maximum she is willing to pay is

vi +

(vi

1

pi

(1

) vi + (vi

pu

pi

vi pi

1

vi

where vi

pu )

pu )

pu

vi

vi pi

1

vi

pi

(1

vi

pi

) vi

Next, we …nd the maximum possible revenue in the absence of free-riding. The expected

26

revenue function is

max E [R] =

N [1

G (pu )] pu + G (pu )

Z

pu

vi

0

=

where pu =

v+c

2

pu

2v

N pu 1

is the uniform price. Therefore, PWYL expected pro…ts take the form

E[

pwyl ]

=

N pu 1

=

N

pu

2v

v+c

2

cN

F

3v c

4v

and we compare these pro…ts to the case of uniform pricing,

expression E [

g (vi )

dvi

G (pu )

pwyl ]

<

u

simpli…es to

<

2(v+c)

:

(3v c)

cN

u

F

=

N

4v

<

2

3

c)2

F: The

v

3

the bound

Note, as marginal cost c !

on the discount factor approaches in…nity regardless of the value on

proportion of loyal buyers

(v

.

Further, if the

then for all values of marginal cost and the discount factor

the inequality will be satis…ed. Let marginal cost c = 0; then the bound simpli…es to

If

<

2

3

<

2

3

:

then the bound is always greater than 1, the discount factor cannot be greater than

1. Therefore, for all relevant values of marginal cost and the discount factor the bound is

satis…ed.

Derivation of equation (19)

We incorporate pricing cost into the repeat consumer game via the …rm’s pro…t function.

We adopt the notation of F = F

where F is …xed cost under PWYL pricing and

represents the cost of pricing. The …rm’s expected pro…t function under PWYL pricing is

then

E[

pwyl ]

=

N

v+c

2

3v c

4v

and we compare these pro…ts to the case of uniform pricing,

expression E [

pwyl ]

<

u

simpli…es to

<

2(v+c) N

(3v c)

cN

u

F

=

N

4v

(v

c)2

F: The

: Note, as marginal cost c !

v

3

the

bound on the discount factor approaches in…nity regardless of the value on . Further, if

27

the proportion of loyal buyers

<

2

N

3

then for all values of marginal cost and the discount

factor the inequality will be satis…ed. Let marginal cost c = 0; then the bound simpli…es to

<

2

N

3

:

References

Cabral, L. 2000. Introduction to Industrial Organization. MIT Press, Cambridge.

Camerer, C. (2003). Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments on Strategic Interaction. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Conlin, M., Lynn, M., T. O’Donoghue. 2003. The norm of restaurant tipping. Journal of

Economic Behavior and Organization 52 297-321.

Dubner, S., S. D. Levitt. 2004. What the bagel man saw. New York Times Magazine June

6.

Duncan, C.P., R. W. Olshavsky. 1982. External search: The role of consumer beliefs"

Journal of Marketing Research 19 32-43.

Gruber, J. 2004. Pay or pray? The impact of charitable subsidies on religious attendance,

Journal of Public Economics 88 2635-2655.

Kim, J., M. Natter., M. Spann. 2009. Pay what you want: A new participative pricing

mechanism. Journal of Marketing 73 44-58.

Lynn, M. 1990.Choose your own price: An exploratory study requiring an extended view of

price’s function. In Advances in Consumer Research 17 710-714, eds. M.E. Goldberg, G.

Gorn, R.W. Pollay. Association for Consumer Research, Provo.

Mead, Rebeca. 2008. Check please. The New Yorker March 21.

Nahata, B., K. Ostaszweski, P. K. Sahoo. 1999. Bu¤et pricing. Journal of Business 72

215-228.

Rochet,J.-C., L. Stole. 2003. The Economics of multidimensional screening. In Advances

in Economics and Econometrics: Theory and Applications, Eighth World Congress, eds. M.

Dewatripont, L. Hansen and S.Turnovsky. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Thaler, R.H. (1992). The winner’s curse: Paradoxes and anomalies of economic life. Prince-

28

ton University Press, Princeton.

Wernerfelt, B. 2008. Class pricing. Marketing Science 27 755-63.

Willig, R.D. (1978). Pareto-superior nonlinear outlay schedules. Bell Journal of Economics

9 56-69.

29