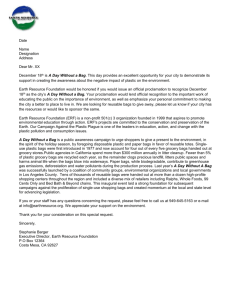

SEC Position Paper - Singapore Environment Council

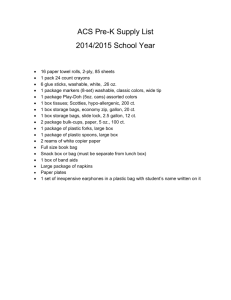

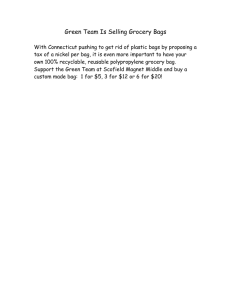

advertisement