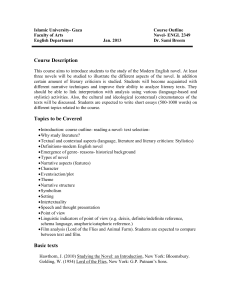

Untitled

advertisement