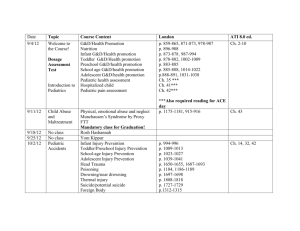

CRPS and the anaesthetist – A problem all round! Dr Meredith

advertisement

CRPS and the anaesthetist – A problem all round! Dr Meredith Craigie, Adelaide, Australia Paediatric Anaesthetist and Specialist Pain Medicine Physician Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia Board member and Chair, Paediatric Pain Working Party Faculty of Pain Medicine, ANZCA Once considered rare in children although it had been reported in adults since 1860, Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) has been described in the paediatric population since the 1970s 1 and is increasingly being recognised, especially in adolescents . CRPS presents a variety of problems for all involved. The child’s problem is one of continuing severe pain out of proportion to the inciting event, allodynia and hyperalgesia with accompanying vasomotor and sudomotor changes of varying severity. Being “experts in managing pain”, Anaesthetists are frequently called on to help manage these patients. This condition presents a number of problems for the Anaesthetist. The aetiology is unknown and a full understanding the pathophysiology remains elusive. Persistent inflammatory activity and changing inflammatory profiles between acute and chronic CRPS have been 2 observed . Alterations in peripheral and central sensitisation with changes in brain processing are 3,4 other lines of investigation . Reorganisation of the S1 cortex of the contralateral side to the affected limb has been demonstrated and appears to be associated with the complaints of 4 neuropathic pain . Most research has been performed in adults. However, quantitative sensory testing has demonstrated thermal and mechanical sensory changes in children with cold allodynia the 5 most common . Diagnosis poses another problem. There have been a variety of diagnostic schemes all based on 6 clinical criteria. The Budapest Criteria are the most recent . They have very high sensitivity with greatly improved specificity compared with the previous criteria set out by the International Association for the Study of Pain. There are four components to the Budapest Criteria. They consist of (1) continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event; (2) report of at least one symptom in three of four categories (sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/oedema and motor/trophic); (3) display of at least one sign at time of evaluation in two or more of four categories (sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/oedema and motor/trophic); and (4) no other diagnosis that explains the signs and symptoms. Although these criteria are commonly used, they have not been validated in children. There are some differences in the presentation of children compared with adults. CRPS is more 7 common in females and more commonly presents in the lower limb . Early adolescence (12 to 14 years) is the peak age of onset although individual cases have been described in much younger 8 children . Onset can follow a wide variety of events, often minor trauma but also major surgery and 7,9,10 . Occasionally, a trigger cannot be identified. A psychological basis for CRPS even immunisation 8,11,12 . has been discounted although psychological factors may contribute to the severity As in most chronic pain states in childhood or adolescence, CRPS is a problem involving the whole 13 family . Somatization, anxiety, and depression occur in up to 60% of patients. Relationship problems with peers, school problems and social withdrawal are common. Caregivers have time away from work, losing income at a time of increased medical expenditure for the child resulting in 14 considerable financial impact . Treatment of CRPS is also problematic. Physical rehabilitation has long been considered an 15 essential element . The problem has been how facilitate it. Over the years, a variety of oral and intravenous medications, sympathetic blockade, regional anaesthesia have been used in an 16, 17,18,19 . Anaesthetists are frequently involved at this endeavour to reduce the severity of the pain stage, implementing and managing interventional therapies. More novel treatments have been 20, 21, 22 . reported including intrathecal analgesia, spinal cord stimulation and intravenous pamidronate However, most children can recover well with non-invasive rehabilitative approaches. Cognitive behaviour therapy or similar therapies, along with physical therapy in a combined approach forms the basis of most intensive inpatient and outpatient programs, and most recently, a Day-hospital 23,24 . Changes in both the child’s and parental willingness to self-manage pain are important program in achieving functional and psychological improvement and may be facilitated by an interdisciplinary 25 team approach . Generally, much better outcomes are expected in children with CRPS although 26 26 the evidence for this is only fair . Relapse rates may be moderately high . However, early diagnosis and referral with appropriate intervention is the key to decreasing pain, restoring function and minimising suffering of children with CRPS. REFERENCES: 1. Fermaglich, DR (1977). Reflex sympathetic dystrophy in children. Pediatr 60(6):881-3 2. Parkitny, L, McAuley, JH, Di Pierro, F, et al (2013). Inflammation in complex regional pain syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis Neurology 80:106-117 3. Lebel, A, Becerra, L, Wallin, D et al (2008). fMRI reveals distinct CNS processing during symptomatic and recovered complex regional pain syndrome in children Brain 131:1854-79 4. Maihofner, C, Handwerker, HO, Neundorfer, B, Birklein, F (2003). Patterns of cortical reorganization in complex regional pain syndrome Neurology 61:1707-15 5. Sethna, NF, Meier, PM, Zurakowski, D, Berde, CB (2007). Cutaneous sensory abnormalities in children and adolescents with complex regional pain syndromes Pain 131(1-2):153-61 6. Harden, RN, Bruehl, S, Perez, RSGM, et al (2010). Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Pain 150(2):268-274 7. Murray, CS, Cohen, A, Perkins, T, Davidson, JE, Sills, JA (2000). Morbidity in reflex sympathetic dystrophy Arch Dis Child 82:231-33 8. Pearson, RD, Bailey, J (2011). Complex regional pain syndrome in an 8-year-old female with emotional stress during deployment of a family member Military Medicine 176(8):876-8 9. Wolter, T, Knoller, SM, Rommel, O (2012). Complex regional pain syndrome following spine surgery: clinical and prognostic implications European Neurology 68(1):52-8 10. Richards, S, Chalkiadis, G, Lakshman, R et al (2012). Complex regional pain syndrome following immunisation Arch Dis Child 97(10):913-5 11. Ciccone, DS, Bandilla, EB, Wu, W (1997). Psychological dysfunction in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy Pain 71:323-33 12. Cruz, N, O’Reilly, J, Slomaine, BS, Salorio, CF (2011). Emotional and neuropsychological profiles of children with complex regional pain syndrome type-1 in an inpatient rehabilitation setting Clin J Pain 27:27-34 13. Gauntlett-Gilbert, J, Eccleston, C (2007). Disability in adolescents with chronic pain: Patterns and predictors across different domains of functioning Pain (1-2)131:132-141 14. Sleed, M, Eccleston, C, Beecham, J, Knapp, M, Jordan, A (2005). The economic impact of chronic pain in adolescence: Methodological considerations and a preliminary costs-of-illness study Pain:183-90 15. Wilder, RT (2006). Management of Pediatric Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Clin J Pain 22:443-8 16. Wheeler, DS, Vaux, KK, Tam, DA (2000). Use of gabapentin in the treatment of childhood reflex sympathetic dystrophy Pediatric Neurology 22(3):220-1 17. Kaplan, R, Claudio, M, Kepes, E, Gu, XF (1996). Intravenous guanethidine in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 40(10):1216-22 18. Cepeda, MS, Carr, DB, Lau, J (2005). Local anesthetic sympathetic blockade for complex regional pain syndrome (Review) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4):CD004598 19. Dadure, C, Motais, F, Ricard, C, et al (2005). Continuous peripheral nerve blocks at home for treatment of recurrent complex regional pain syndrome 1 in children Anesth 102(2):38791 20. Stanton-Hicks, M, Kapural, L (2006). An effective treatment of severe complex regional pain syndrome type 1 in a child sing high doses of intrathecal ziconotide J Pain Sympt Manage 32(6):509-11 21. Olsson, GL, Meyerson, BA, Linderoth, B(2008). Spinal cord stimulation in adolescents with complex regional pain syndrome type 1 (CRPS-1) Eur J Pain 12(1):53-9 22. Simm, PJ, Briody, J, McQuade, M, Munns, CF (2010). The successful use of pamidronate in an 11-year-old girl with complex regional pain syndrome: response to treatment demonstrated by serial peripheral quantitative computerised tomographic scans Bone 46(4):885-8 23. Lee, BH, Scharff, L, Sethna, NF et al (2002). Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral treatment for complex regional pain syndromes J Pediatr 141:135-40 24. Logan, DE, Carpino, EA, Chiang, G et al (2012). A Day-hospital approach to treatment of pediatric complex regional pain syndrome Clin J Pain 28:766-74 25. Logan, DE, Conroy, C, Sieberg, CB, Simons, LE (2012). Changes in willingness to selfmanage pain among children and adolescents and their parents enrolled in an intensive interdisciplinary pediatric pain treatment program Pain 153(9):1863-70 26. Bialocerkowski, AE, Daly, A (2012). Is physiotherapy effective for children with complex regional pain syndrome type 1? Clin J Pain 28(1):81-91