Talking Trade: Summary Report of the CGA

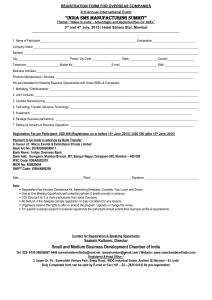

advertisement

Talking Trade Summary Report of the CGA‑Canada Roundtables on International Trade July 2014 By the Certified General Accountants Association of Canada 2 Talking Trade Summary Report of the CGA‑Canada Roundtables on International Trade July 2014 3 4 Table of Contents 1.Introduction............................................................................................7 2. What we heard: A summary of the SME roundtable discussions..........9 3. Where do we begin? Business challenges in going international...........11 4. The Great Unknown: Acquiring local market information....................15 5. Opening the door: Trade missions and trade shows...............................21 6. Going native: Marketing and maintaining a local presence...................23 7. Understanding foreign business cultures and navigating bureaucracy...27 8. Getting our own house in order: Addressing domestic challenges.........31 9. Conclusions and next steps.....................................................................37 10. Appendix A: List of roundtables, dates, places, partners.......................39 11. Appendix B: List of participants............................................................41 5 6 Introduction 1 Canada has always been a trading nation. In recent years, the federal government has worked to open more doors to trade by pursuing an ambitious trade agenda and securing a number of free trade agreements with new partners, most notably the recent Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union and the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CKFTA). But free trade agreements by themselves will not improve Canada’s sagging international trade performance. As the government notes in its recently released Global Markets Action Plan, “Canadian firms, and SMEs in particular, face an uphill struggle expanding into emerging markets, where the business culture, regulatory environment and language can be particularly challenging, even with a trade agreement.”1 Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) are playing an increasingly important role in international trade and the government’s plan sets ambitious targets to grow that trade performance even further by encouraging SMEs to expand into emerging markets. The plan also promises changes to the government’s “roster of effective trade promotion tools” in order to assist Canadian businesses, and particularly SMEs, to overcome the challenges of doing business internationally. “Canadian firms, and SMEs in particular, face an uphill struggle expanding into emerging markets ... even with a trade agreement.” Last year CGA-Canada published Canada’s Global Trade Agenda: Opportunities for SMEs, a report that examined the trade performance and potential of Canada’s SME sector and summarized the obstacles they encounter doing international business.2 From November 2013 to May 2014, the association convened roundtables in different regions of the country to get beyond the statistics and hear first-hand experiences of SMEs that are actively engaged in international trade. We also asked for their ideas on how those “trade promotion tools” should be reformed in order to be more effective. This report summarizes what was heard at the roundtables, which were held in Halifax, Quebec City, Ottawa, Mississauga, Saskatoon, and Vancouver. Following further consultation and analysis, CGA-Canada will publish a report later in 2014 that makes recommendations to policy makers and stakeholders. 1Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. Global Markets Action Plan: The Blueprint for Creating Jobs and Opportunities for Canadians Through Trade. Ottawa: Government of Canada, 2013. 2Laurin, Jean Michel. Canada’s Global Trade Agenda: Opportunities for SMEs. Ottawa: Certified General Accountants Association of Canada, 2013. 7 8 What we heard: A summary of the SME roundtable discussions 2 As a Halifax roundtable participant reminded us: “A small business is not a little big business.” Statistics Canada defines SMEs as those businesses with fewer than 500 employees and $50 million in gross revenue. Small businesses are defined as having fewer than 100 employees (with micro businesses having fewer than five), while medium-sized firms are those with between 100 and 499 employees. Most research and public policy analysis focuses on the entire SME sector. However, the most immediately apparent observation from our six roundtable consultations is the enormous difference between small businesses and midsized firms when it comes to the magnitude of the challenges they face and the resources available to address those challenges. When a mid-sized firm decides to expand into a new market, it usually has the internal resources – including people, knowledge, finances and time – to develop and execute a strategy. A small firm of two or three dozen employees is unlikely to have the same resources and may not even know where to turn to find the assistance it requires. For many such firms, meeting Friday’s payroll is the most immediate preoccupation, and time is the scarcest resource. The firm’s leadership is unlikely to be able to devote as much attention to the expansion plan as it requires. More importantly, expanding into a new market, particularly an emerging market, is likely to require three or more years of effort including maintaining a presence in that market before any results are seen. Few small businesses can invest for such a period of time without seeing any return. “There’s nothing like a bad experience for you to say I don’t want to do this again.” Small businesses may feel pressured into expanding internationally or see a good opportunity to make a sale. However, as a participant cautioned, “Profitable growth is the key. Particularly for SMEs, a $50,000 loss is $50,000 less equity. It has a material impact on the business. Anyone can sell, but it’s hard to sell at a profit.” Another participant who advises SME manufacturers on international trade said he spends much of his time explaining to clients why they don’t want to expand into certain markets and why they should focus their energies on local markets, at least until they have gained more experience and international knowledge. “There’s nothing like a bad experience for you to say I don’t want to do this again.” 9 Despite these cautionary notes, participants were generally bullish about the opportunities for Canadian SMEs in international markets. But they stress it is important to be realistic about the time, energy and knowledge required to be successful. This view was voiced most emphatically by the Saskatoon participants and it was interesting to note the different regional perspectives that emerged through the discussions. Saskatchewan businesses, it was pointed out, have to export because the local market is too small to support anything other than local service providers. Several of the businesses represented at the Saskatoon roundtable do virtually all of their business outside of the province. It is important to be realistic about the time, energy and knowledge required to be successful. The perspective was different in Halifax where participants noted that Nova Scotia businesspeople tend to think of international markets as being Prince Edward Island or even the next county. During a discussion about the emerging markets of the southern hemisphere, one said, “For us, south means Maine, maybe Boston.” Yet, it must be noted that some of these participants are successfully doing business all around the world. On the subject of the role of government, the response was the same at all of the roundtables. The first comment was usually something along the lines of, “government should just get out of the way.” However, participants quickly acknowledged that government does have a role to play and there are important functions that government is uniquely placed to provide. 10 Where do we begin? Business challenges in going international 3 “I would say, from everything that I’ve seen and learned, the challenges when you’re starting, especially a small business, you don’t know what you don’t know,” a participant told us. “The gap appears to be you don’t know what you need; there are people who don’t know how to get you that information in a time sensitive fashion; and then the processes to move it through.” “Most businesses here are small businesses and they need a lot of handholding,” said another participant. “I don’t think there are a lot of programs out there from an export perspective to show somebody that if they’re in PEI and they sell to New Brunswick, they’re now exporting beyond their borders. How do we recognize that, how do we reward that, and how do we encourage that? It takes a lot for a small business to take on that risk.” For the true entrepreneurs, not having all the answers is not necessarily a problem. As one participant put it: “For us, our first step is by trying things and making mistakes. It is true it can be expensive, but that is how we started. When you never exported internationally, you don’t realize how much improvisation there is.” That approach can be dangerous for some SMEs, noted a participant who advises small businesses. “Most of these companies don’t have the means to try things and make mistakes. A mistake can be a fatal one for some companies. SMEs need to be very disciplined.” “Most of these companies don’t have the means to try things and make mistakes. A mistake can be a fatal one for some companies. SMEs need to be very disciplined.” One way of avoiding costly mistakes is to contract business consultants who have the expertise that the SME management may lack. “First you have to educate the SME on what they’re getting themselves into, and then prepare them for what they are going into,” said a participant who advises SMEs. “Who does that education? It’s a third party. It’s someone like me who’s had 20 years of experience doing business internationally.” But some of that advice can also be obtained through various services provided by both federal and provincial governments. At the federal level, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), Export Development Canada (EDC), the Canadian Commercial Corporation (CCC) and the Canadian Trade Commissioner Service (TCS) are among the agencies that provide assistance to businesses at various stages and different situations. The challenge for SMEs is to navigate the plethora of programs and services available and understand which is the appropriate agency to approach. 11 “It would really help companies such as ours to have a single point of contact for federal government programs,” said a participant, triggering a round of applause from the rest of the group. “At the provincial level, we have it. There’s a fellow who is a senior business advisor for the Ministry of Small Business. He’s a valuable resource for us at the provincial level. Something equivalent at the federal level would be great.” “Businesses in this region are very well served,” said a Quebec City participant. “We have interesting programs, but the issue is the lack of knowledge from business entrepreneurs of those programs. Where to start? Which door to knock on? Many businesses wonder where they need to go to find the appropriate assistance.” “Where to start? Which door to knock on? Many businesses wonder where they need to go to find the appropriate assistance.” Access to finance is always a challenge for SMEs and it was raised at several of the roundtables. “It’s very expensive to do market development. In the USA, when a SME starts with $4 million of capital, that is not much. But here if an SME starts with just $1 million, that is a very good amount of capital. Developing our business internationally is quite expensive. Unfortunately, a lot of SMEs do not have enough capital.” While many SMEs have very positive relationships with their banks, those that deal in emerging technologies or don’t have a proven track record are not as well served even though some of these firms may have the best potential to succeed internationally. “Dealing with a bank is like having an umbrella when the weather is nice. But when it starts raining, you think they are there to help, but it is not necessarily the case. The other problem of dealing with a bank relates to our industry. We are a high-tech SME which makes it more difficult to get capital. The bank services work well if you are buying a car, but do not work as well with our industry. It is even more difficult with a patent.” A participant from the banking sector suggested that businesses should be more proactive and look to their bankers as advisors. “A lot of times, banks are the last people that are going to be contacted in order to get the transaction done. The first question we get is how much is that going to cost? And a lot of times they’ll say, oh that’s too expensive, I’m just going to hope for the best and do this on an open account. So cost, whether it’s for the manufacturing, whether it’s for financing advance payment that is received from the importer, and other costs involved, I think there’s got to be, I’m not going to say better education, but a lot more consulting on the part of the lawyers, accountants and business advisors.” 12 “The challenge is to find the right financing at the right time and know on which door to knock,” said another participant. “There is often confusion between BDC and EDC. There should be a single ‘one-stop shop’ for SMEs. It would be much easier for businesses who are taking their first step.” Participants at all of the roundtables commented on the value of talking to other businesspeople who have international experience. “If you can identify across Canada a person who knows about a market and an industry and has practical experience… I don’t really care about book knowledge, I’m talking about somebody who has case studies in his head. And he’s accessible to us. A 15 minute conversation with him, a meeting with him, would do us more good than anything else.” The advice of a mentor is even valuable to someone who is already quite familiar with a particular market. A participant who was born in India said that before doing business in that country he sought the advice of a Canadian businessperson who had 15 years of experience doing business in India. He knew that the advice he would receive would be more objective and trustworthy than what he would receive from friends back home. “There should be a single ‘one-stop shop’ for SMEs. It would be much easier for businesses who are taking their first step.” But how does one go about finding a mentor? “The program officers at ACOA (Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency), EDC, BDC, etcetera, have a good knowledge of all of their clients and should be able to recognize businesses with complementary interests,” noted a Halifax participant. “They should be able to provide a matchmaking service, but I’ve never seen them do that. They could help match up businesses as mentors.” The CGA-Canada background paper, Canada’s Global Trade Agenda: Opportunities for SMEs, reported on several surveys in which SME owners or managers identified a lack of internal knowledge or expertise as an issue. Although some roundtable participants readily acknowledged gaps in their own international business skills, few appeared to be seeking formal training to address those gaps. An exception was the Quebec City roundtable, perhaps because Québec International, which partnered with us to hold the roundtable, provides some training services to its clients. That training includes not only technical and logistical aspects of international business, but also insights into foreign business cultures. “If in 2010 I had received some coaching about distribution networks, then maybe in 2011, 2012, 2013, I would not have hit the wrong targets,” said one of the Quebec City participants. “What I learned since from my training is that a good distributor is not the one that is the most interesting. It is the distributor 13 who is able to deliver the product and to follow your product throughout its course.” “If in 2010 I had received some coaching about distribution networks, then maybe in 2011, 2012, 2013, I would not have hit the wrong targets” The Forum for International Trade Training (FITT) has noted that Canada faces a gap in international trade capabilities – that is, that not enough Canadian workers have the knowledge, skills and abilities necessary to facilitate international trade.3 Much of that knowledge and skills can be obtained through existing channels – courses at universities and colleges, seminars and webinars from trade associations and other private sector providers. But perhaps there is a need for advisors from BDC, EDC and the Trade Commissioner Service to promote such skills training to their clients. As this chapter began, often the biggest obstacles are the things that we don’t know we don’t know. 3 Forum for International Trade Training. Report of the FITT Human Resources International Trade Sector Study. Ottawa: Forum for International Trade Training, 2013. 14 The Great Unknown: Acquiring local market information 4 One of the biggest challenges of entering any new market is obtaining information about the market. This includes, but goes beyond, statistical data about the size of the market and leads on potential customers. It also includes finding suitable local partners, agents or suppliers. As the CGA‑Canada background paper Canada’s Global Trade Agenda: Opportunities for SMEs put it, taking advantage of opportunities in emerging markets “requires companies to know about specific opportunities, and to be able to reasonably assess their commercial value and the risks associated with pursuing them.” Government plays a role here, as can private sector consultants. However, many participants emphasized that nothing replaces actually going to the country and becoming familiar, firsthand, with how business is done there. “It’s the three P’s: presence, persistence and patience,” said one participant. “You’ve got to go. You’re not going to develop an international business by staying here. You’ve got to see first-hand. I had a particular picture of China before I went, and after I went I can tell you pretty much every preconception I had was shattered – not changed, they were completely shattered. When you’re there, you will see the opportunities that you’re not going to see by Googling it or reading some article on it or whatever. You’ve got to go.” At a different roundtable, another participant expressed a similar view: “In Canada, before we do something, the first place we go is to the government for a handout to say, can you fund this project, can you fund this research mission. It’s crazy. You spend more time dealing with the government bureaucrats. Just go and get on a plane, go meet the people, go find the trade association and do the business. And don’t worry about getting the government involved because in our experience, there’s more time consumed in this non-productive activity in filing reports.” “It’s the three P’s: presence, persistence and patience. You’ve got to go. You’re not going to develop an international business by staying here.” Many of the roundtable participants were “pulled” into international markets by their customers. Rather than choosing to pursue a particular market, they were sought out by new customers who came looking for their product or service. Often, an existing customer’s referral was the starting point. This may be the ideal way for an SME to expand internationally as it reduces risk and cost. 15 Regardless of how and why a firm chooses to enter a new market, the first need is for information. The Canadian government, and other national governments, produce reports and statistical data on a country-by-country basis, sometimes including market profiles for specific industry sectors. But participants indicated that the information may not always meet their needs. “There isn’t a lack of information out there,” said one participant. “There’s a disconnect between what an SME really needs and how to interpret that information in terms of the products and services they offer and whether or not its tailor-made and appropriate, especially on a technical side of things.” “There isn’t a lack of information out there. There’s a disconnect between what an SME really needs and how to interpret that information.” “Knowledge is power,” added another participant. “Knowledge comes from access to information through the industry guys. Understanding what is happening in each region and actually conveying that information back and forth. Telling them, these are the barriers to entry, these are the challenges you’ll face, these are the things you need to look at before you go. That is the kind of information that will empower businesses. That’s the role that we see the federal government playing.” A couple of participants said they prefer the market information available from the American government and that it was more useful for their purposes. Australia’s Austrade was also singled out. One participant said that HSBC produces trade reports that are better than those produced by the Canadian government. That prompted the observation that governments often try to reinvent the wheel by investing a lot of energy in trying to match something being produced by the private sector. A better approach might be to consider ways of partnering with that private sector enterprise. Many firms look for local partners when entering a new market. In some situations, this may even be a legislated requirement. However, how does one find a reliable, competent partner in an unfamiliar country? Participants indicated this is an issue where they expect the Canadian Trade Commissioner Service to provide real value. “One thing I would suggest, if you’re dealing with international markets, rather than going in and opening your own office, try to work with partners there,” said a participant. “If you can find some reliable partners who know the market there, use them to gain some business and work in that country. Otherwise there will be issues, political issues, all kinds of issues. You don’t know the market. The challenge is finding a reliable partner. This is where if the trade commissioners had local knowledge, they could provide value.” 16 “It’s really about finding a local partner that you can work with and trust,” said a participant at a different roundtable. “And my guess would be that’s probably the single biggest decision that can go right or wrong, is choosing that partner. What if the government could actually help vet that partner somewhat and reduce the number of misfires? If, for example, I had narrowed the process down to three people and I could call the trade commissioner and ask, what can you tell me about these three people? If they could actually get you the real goods, I would think that would go a long way to facilitating business.” With over 150 offices around the world and across Canada, the Canadian Trade Commissioner Service provides on-the-ground support to Canadian companies doing business internationally. Yet that level of local knowledge – the ability to provide advice on potential local partners – is not something they are always able to provide. Two reasons for this were identified in the discussions. The first is that trade commissioners may feel that advising clients on who they should or should not do business with may be stretching their mandate. The second reason identified is the relatively short period of time that each trade commissioner spends in each post. Most postings are three to four years in duration – not enough time to develop deep enough local market knowledge or local contacts to provide that kind of value. “It’s really about finding a local partner that you can work with and trust. And my guess would be that’s probably the single biggest decision that can go right or wrong.” A suggestion raised at several roundtable discussions was that increasing the duration of foreign postings would greatly improve the quality of service offered by the foreign-based trade commissioners. As one participant explained it, “the first six months they’re trying to find where the washroom is, and the last six months they’re trying to figure out where do I go next. So you’ve got two good years, and there’s a huge learning curve. So what would happen if we changed it from three years to four year postings? There’s a 50 per cent improvement.” “In countries like Mexico and China, things are done on the basis of personal relationships and you don’t have the luxury of breaking in new people every two years,” said another participant. “So you’ve got to do that kind of work yourself. Use them (trade commissioners) when you can, but their role is very limited.” Another suggestion was to supplement the diplomatic staff with locally recruited commercial officers, people who have local market knowledge and connections and will stay with the overseas office for a longer duration. These people would also be well-placed to advise on cultural issues, as discussed later in this paper. While trade commissioners are based both across Canada and abroad, they don’t necessarily function as smoothly as they might. “There are trade 17 commissioners in Ontario and they’re sector specific,” said a participant in that province. “I would love to see the Trade Commissioner Service in Ontario and the Trade Commissioner Service abroad co-operate. Because often you ask a trade commissioner in Abu Dhabi what the Americans are doing, what the French are doing, they know. They know everything. But to know what their counterpart in the same ministry is doing in Ontario – no idea.” While our participants had much to say about the Trade Commissioner Service, that in itself should probably be seen as a positive reflection on the service. By and large, they seemed to be more familiar with and have more personal experience with the TCS than other trade promotion programs. While their comments were mixed, generally speaking, the smaller the business the less likely they were to have been satisfied with their experience. This is consistent with the TCS’s own client satisfaction survey and may be an indication that small businesses, especially those new to exporting, may require a level of service that the TCS is not designed to provide. Generally speaking, the smaller the business the less likely they were to have been satisfied with their experience. Several of the roundtables discussed extensively the role of chambers of commerce and trade associations. It was pointed out that in many parts of Europe, the Middle East and South America, chambers of commerce play a much greater role in providing trade assistance programs to businesses on behalf of government. However the nature of chambers of commerce in those regions is quite different. They are the municipal licensing authority for businesses and membership is mandatory. That gives the chambers greater financial resources and a stronger mandate to deliver such services. “Almost all programs that governments (in Europe and South America) do are via the chambers – via a national chamber, and then the national chamber distributes among its member chambers. So there’s real integration between government, not-for-profit organizations and the private sector.” Although the structure is different here, many participants believed that there is an opportunity for governments and chambers of commerce to work more closely on the delivery of services. And certainly businesses that are looking to expand internationally should be involved in their local chambers, if they aren’t already. As one participant put it, “Once you’re on one chamber, the other ones talk to you a little more and you have a little network.” Overseas Canadian chambers of commerce are an often overlooked resource, noted one participant. “Generally those chambers of commerce are people that not only have done business in that part of the world for an extended period of time, but they also tend to be the Canadians that live in that world and never left it.” 18 Many participants spoke positively of their experiences working with trade associations, both in Canada and overseas. Trade associations can be a helpful ally, not only for the businessperson, but for government as well. In addition to possessing a deep understanding of their specific industry sector, they also have a strong network of members or contacts both domestically and in foreign markets. But perhaps most importantly, they have a long-term perspective that governments sometimes lack, a point that we will return to in our last chapter on domestic challenges. 19 20 Opening the door: Trade missions and trade shows 5 Roundtable participants had different experiences with government-led trade missions. Some spoke highly of the 1990s-era Team Canada trade missions, but acknowledged that a different approach is needed today. A more common view was that a sector-specific, and often industry-led, approach is more effective for SMEs. “One thing that we’ve had very good experience with is trade missions. What is interesting about trade missions now versus 15 or 20 years ago is that I don’t need you to tell me who are my customers. The Internet does a great job of that. So I don’t need help in finding customers anywhere. Where a trade mission helps is that you can attract a high-level CEO, COO-level person to attend because a Canadian mission has a certain aura. That helps.” One participant had a positive experience with a provincially-led trade mission to India. “They set up meetings with 20 companies for 30 minutes each. In the end, there wasn’t a fit in that particular case. But we actually met 20 credible companies and we probably could have done business with five or six of them.” But not all participants were as positive about trade missions. A recent trade mission to Brazil where small Canadian firms were introduced to the local branch of a large multinational firm was cited as an example. “Our experience is that trade missions tend to be about opportunities, and I’m not really interested in opportunities. I’m interested in sales. It might be just a sale of a ten thousand dollar widget. And to go and be introduced to a large multinational company is a waste of their time and it’s a waste of my time, because they’re only interested in either buying us outright or buying our IP, or something that’s got seven figures attached to it. Anything less is beneath their radar.” “Where a trade mission helps is that you can attract a high-level CEO, COO-level person to attend because a Canadian mission has a certain aura. That helps.” “Unless they’re very industry-specific, I don’t think trade missions are that useful,” said another participant. “Often, some of the government agencies tend to be more focused on the larger deal size. The Canadian Commercial Corporation for example, is not going to touch anything under a couple of million dollars. So as a small company, you start small and you grow in a market. You don’t start with a five million dollar contract. If I’m already at a point where I can do five million of business, I probably don’t need CCC.” 4DFATD. “Trade Commissioner Comprehensive Client Survey – 2013.” 2013. www.tradecommissioner.gc.ca/eng/document.jsp?did=140716. 21 One participant told how the trade commission of a European country successfully used a reverse approach to trade missions, identifying a select group of potential customers in the renewable energy sector in the United States and flying them to Europe. The government worked with local European companies to plan the mission, made (and paid for) all the travel arrangements, and worked with the companies on follow-up after the visit. Other participants noted that this approach is commonly used by European countries. “Big companies are remembered, but without regular contact, smaller companies will be forgotten. Relationships and trust must be built before deals are going to be concluded.” One of the biggest problems with trade missions however, rests with the businesses themselves – not following up properly. “Government-led trade missions provide a good opportunity to meet local companies. However, follow-up is usually weak. Big companies are remembered, but without regular contact, smaller companies will be forgotten. Relationships and trust must be built before deals are going to be concluded.” That comment illustrates perhaps the single biggest challenge that SMEs encounter when doing business internationally – marketing. Specifically, the cost of maintaining a local presence and demonstrating a long-term commitment to a market, a topic addressed in the next section of this paper. Some of the businesses represented at the roundtables make highly specialized products that are marketed to very narrow niche markets. Others are embedded within global value chains, making intermediate products that are sold to other manufacturers. In both cases, potential customers are a relatively small and easily identifiable pool of businesses. However, for products that are marketed directly to consumers and even for many business-to-business products, cutting through the clutter of the marketplace is still a challenge. For these businesses, trade shows which connect producers, distributors and retailers, are an important avenue for building sales. Participants reported two challenges in attending trade shows. One is the cost, which for many small businesses can be substantial and prohibitive. The second challenge is bureaucratic red tape, particularly at the border. Both challenges are elaborated on in the next sections. 22 Going native: Marketing and maintaining a local presence 6 “What people don’t seem to understand is that sales takes a long time. There’s a real disconnect between the time that it takes to do business and when you can expect a return.” As one participant said, the biggest impact government could have on his business would be the ability to offset travelling expenses related to building a presence in a foreign market. “It’s a very expensive process. I know there are programs out there. We don’t use them – there’s more red tape than filling out an income tax return. Some offer 50 per cent. Maybe if there was less red tape, fine. But even 50 per cent is not sufficient for a lot of SMEs. They need 100 per cent on their sales and marketing expenses. That’s a big challenge – just building a presence.” Another participant agreed, saying the need is for tax incentives that offset costs related to marketing and sales, and have simple, verifiable rules. Several participants noted the value of Canada’s research and development programs, but pointed out that there is a gap between the R&D and the marketing. “We have good programs in Canada – SR&ED in particular – for the technology sector. They help with cost competitiveness for our research, but there’s a big gap from there to commercialization. And commercialization involves selling to other countries. Even the programs that do exist that help with market development tend to be oriented towards officially-sanctioned trade events. Well, that’s not where you’re going to find your customer. I know who my customer is – I’m in a very, very specific field. I’ve never seen a trade show that’s going to get me to them.” “ ... The reality is that doing business internationally requires money and the capacity to take risk.” “The main challenge is that a lot of entrepreneurs put all their money into product development rather than commercialization of the product,” said another participant. “An entrepreneur who has emptied his pockets during product development will have a hard time to export the product at the international level. The reality is that doing business internationally requires money and the capacity to take risk.” Another technology sector representative said he is able to claim back, through the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) program and the Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP), 70 to 80 per cent of the cost of hiring an engineer to do scientific research and development. “I can’t do anything like that for getting a guy into China for a week. If I get a guy 23 into China for a week, that’s going to cost me… let’s say between five and ten thousand dollars to get to China, to travel, to see people, to stay in a hotel. And I need to do those trips every two months. Well, that’s another staff person. We’re only at 20 people. Another staff person, that’s another five per cent. So you start to see how marketing is a massive potential cost that we either don’t do or we do with assistance.” At one roundtable, the Program for Export Market Development (PEMD) was brought up as a potential solution. PEMD was a federal program that supported SMEs to export and to develop new markets. It was discontinued in 2006 after 35 years, although a component of PEMD that assists trade associations continues. A revitalized and updated version of PEMD, it was argued, would help to address the marketing challenges that SMEs face. “Now, this is where everyone breaks the rules in a different way, right? And Canada is Mr. Clean because we don’t break the rules – and that’s the problem.” Another roundtable identified a problem with many existing government programs – and with PEMD as well – having a bias toward products. Service providers are not eligible for some federal programs, a problem in a modern economy that is increasingly based on high value services. One service provider in the high-tech sector said that government sometimes sends misleading messages to potential foreign customers or investors. He said that because of Canada’s R&D tax incentives, the country is sometimes positioned as a cheap place to do research. “That’s a real issue for us, because we’re not that cheap. Our value proposition is the talent we have, the quality of product we are able to do, and maybe to do it at a relatively good price. But not in the same scale as other countries. When you’re trying to sell a service that can be done somewhere else, what you want to tell them is how your product is unique.” A “Buy Canadian” strategy equivalent to the U.S. Buy American Act was suggested at a couple of roundtables, but received mixed reactions. As one participant put it, “This is a world of no borders and no tariffs. Now, this is where everyone breaks the rules in a different way, right? And Canada is Mr. Clean because we don’t break the rules – and that’s the problem.” Most participants did not advocate protectionist measures or subsidies that counter international trade rules, but there were suggestions that government could do more in terms of commercialization of technology and government procurement. “If the government is going to invest in Canadian technology companies (through R&D funding programs), it needs to invest in supporting them to make domestic sales as other countries do.” 24 The United States, it was pointed out, does that effectively through defence industry procurement by way of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). A panel led by Tom Jenkins released a report last year to the Minister of Public Works and Government Services that recommended similar strategies be adopted for Canadian military procurement and the government has followed many of the Jenkins recommendations in its new Defence Procurement Strategy.5 But apart from military procurement, government could stimulate domestic businesses in other ways as well. A participant explained: “Everything I’ve read is that before you can export, you have to have a domestic market. You have to have a good product and you have to prove it in your own domestic market, and then you can go out and sell to the world.” One way of doing that would be for government to more effectively outsource opportunities, he said citing SNC-Lavalin as an example. “It is a big player. In Quebec in the sixties and seventies with their big dams, rather than hiring engineers and making them civil servants, the Quebec government turned around and gave the business to the private sector so that they could then develop the expertise through government projects that they could then export outside.” Several participants, at a couple of different roundtables, were small-scale examples of the importance of government procurement, crediting government as being their first customer and providing them with the opportunity to fully develop and showcase their product. “We really struggle to build that made-inCanada brand … in the European markets across the ocean, it’s not seen as something that adds a lot of value so some work needs to be done there.” Creating a strong Canadian brand that Canadian companies could leverage in their marketing is another role that participants saw for government. In Budget 2014, the federal government announced plans to develop a “Made-inCanada” branding campaign similar to a successful Australian initiative.6 It’s an idea that was raised at several roundtables and was viewed favourably. One manufacturing firm that has bucked the trend to offshore its manufacturing has already tried, with mixed results, to turn that into a marketing advantage. “We really struggle to build that made-in-Canada brand. It’s something that in Canada has become more recognizable ever since the recession. In the US, it has taken hold much more than I ever thought it would. But certainly in the European markets across the ocean, it’s not seen as something that adds a lot of value so some work needs to be done there.” 5Jenkins, Tom. Canada First: Leveraging Defence Procurement Through Key Industrial Capabilities, Report of the Special Advisor to the Minister of Public Works and Government Services. Ottawa: February 2013. Also Public Works and Government Services Canada. Defence Procurement Strategy. Ottawa: 2013. http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/app-acq/stamgp-lamsmp/sskt-eng.html. 6Government of Canada. The Road to Balance: Creating Jobs and Opportunities. Ottawa: February 2014. p109. 25 Other participants noted that Canada has qualities that are viewed very positively in parts of the world, particularly Asia. They said that a “made-inCanada” brand would have tremendous value in those markets. 26 Understanding foreign business cultures and navigating bureaucracy 7 Obtaining local market information can be challenging enough, but understanding the subtleties of different business cultures is another matter altogether. For example, sending poorly chosen flowers to a client in China could send the entirely wrong message. Even how you dress may matter much more in another country than it does in Canada. “These things are very important,” said a participant. “My first trip to China, I have a Chinese partner over there. She would phone me at 7:30 in the morning and say, today you wear a black suit, a white shirt, and a black tie because we are going to be dealing with government officials today and that’s the way they will be dressed. In a lot of countries, these things are very symbolic. None of us around this table wants to feel uncomfortable by a guest that’s coming in.” Another participant who has worked abroad noted that a lot of businesspeople are seduced by the size and potential of a market without taking the time to really understand it. “If you’re not going to invest the time and also understanding the people of China, South Africa, Brazil or wherever, and get a grasp of how they negotiate, why they do business the way they do, you’ll run into a lot of obstacles. Even if it’s just to take on staff from that part of the world to work in your company. If you don’t have a grasp of their office mentality or what makes them tick in terms of a culture and work practices, again, you might be banging your head against the wall because you’re used to how a Canadian filing process works, but it’s completely different when you’re in Shanghai or when you’re in Taipei or in South America.” “In a lot of countries, these things are very symbolic. None of us around this table wants to feel uncomfortable by a guest that’s coming in.” Finding employees here in Canada with the skills to understand different markets and different regulatory environments is another major challenge, noted a participant. “We are lucky here to have a multicultural population to draw from. We can find people who speak different languages or come from different cultures, but whether they have the business skills and experience that the business needs is another matter.” “Hiring employees who speak the language of the intended market is advantageous, but it increases HR challenges and training expenses for employers,” said another participant. “In small firms of five or ten employees, it is an additional challenge when the owner is travelling all the time and unable to invest time in the employees.” Is there assistance available for that, she asked, bringing us back to the skills and knowledge problem discussed earlier in this paper. 27 As another participant pointed out, hiring people because of their language skills or cultural knowledge is a luxury that only larger SMEs can afford. “I would love to hire someone who speaks a certain language, but it’s not going to happen. We haven’t got that depth. So we have to focus on markets where we can deal with people in English or French. Maybe a medium sized company can afford that. I have to focus on markets where sales costs are low because it’s a long-term process.” “Languages are very important for making personal connections. But in reality, I have seen very few contracts that are not in English,” noted a lawyer at one of the roundtables. “There is an awful lot of red tape at the international level and it’s difficult for small businesses to navigate or even identify it.” Foreign business cultures can seem confusing, but businesspeople can overcome that through education and experience. Foreign regulations are another matter altogether. Helping to unravel overseas red tape is another area where government can play a welcome role for businesses, particularly for small businesses whose limited resources can be easily strangled by bureaucracy. “One of the concerns is there is stuff I don’t know, and what I don’t know is going to catch me,” said one participant. “There is an awful lot of red tape at the international level and it’s difficult for small businesses to navigate or even identify it.” One participant provided a concrete example of regulatory challenges: “That’s where government can play a role, helping to sort out regulatory issues… Every country has its own regulatory environment. We’re trying to do business in Turkey and it’s amazing. We phone Ottawa and say ‘how do we get through this one regulatory hurdle?’ And they just don’t have a clue. They can’t help. “We sell fish oil,” he explained. “Turkey wants to have a document signed by Health Canada that says every fish that was caught and used in the fish oil was healthy. No other country in the world wants that. They say the product has to be healthy. But these trawlers are catching millions of fish. How do you know that each one was healthy? No one will sign that because you can’t prove it. And it’s all in interpretation. We’ve spent 18 months trying to sort that out. And I don’t know if it’s a trade barrier or just some bureaucrat in Turkey who doesn’t know what he or she is talking about. But there’s millions of dollars of business at stake on that one decision.” Helping businesses to sort through the tangle of a foreign country’s regulatory red tape is an important role that the Trade Commissioner Service can provide, both domestically and overseas. But to do that requires resources, specifically well-trained people. As one participant put it, “I would say that the federal 28 government talks trade facilitation a lot. But, you know, I would say on the other hand, a lot of the programs, a lot of the regulatory environment that importers and exporters need to navigate through requires government service. It requires a response within a reasonable time, that sort of thing. But government departments are seeing their budgets squeezed.” A participant at another roundtable put the message more bluntly. “If I were to tell the prime minister something, it would be put your money where your mouth is. But more specifically, look at the boots on the ground.” 29 30 Getting our own house in order: Addressing domestic challenges 8 Our Vancouver roundtable was held shortly after the resolution of a labour dispute that shut down Port Metro Vancouver’s container terminals for more than a month and the federal government earned heated criticism from the roundtable participants for its perceived lack of involvement in the dispute. It served as a good illustration though, that many of Canada’s international trade challenges are here at home and domestic in nature. Regulatory red tape is something that is always sure to get a rise out of businesspeople. But it’s not only foreign red tape as discussed in the previous section. Regulatory uncertainty in Canada can be just as problematic. One participant, while complimenting overseas trade commissioners, became quite animated when comparing them to the domestic International Trade personnel. “There’s a huge difference between DFAIT in Ottawa and the trade commissioners in the country itself. DFAIT (now named DFATD) in Ottawa, from our perspective, has been useless. We go and ask for an interpretation in terms of the rules. Can we trade in these countries? And they’ll say, well, read the legislation. And I say, well we read it and we don’t understand the paragraph. I can’t get an answer. You know, in six months you can’t get a response. They just won’t interpret it. If you violate it, they’ll prosecute you… or someone will. But they won’t give you advice.” “I don’t know that the higher levels have made that connection. When cutbacks happen, it’s hard to facilitate trade.” Cutbacks in the public sector have only increased that problem, said a participant at another roundtable. “We definitely see it with CBSA (the Canada Border Services Agency). In order to jump through the hoops that need to be jumped through… And whether it’s CBSA or other government departments, their goals are worthy. I think that importers and exporters want to comply with whatever needs to be done. But we’re just seeing delays, and whether it’s processing times for permits, documents, what have you. And the same goes for rolling out new programs. I don’t know that the higher levels have made that connection. When cutbacks happen, it’s hard to facilitate trade.” Another participant offered a different example: “We worked with an Australian firm in partnership on a number of installations. But just the difference in dealing in Canada to get a visa to go to Saudi Arabia takes six weeks here. It takes two days in Australia. That feeds into our scheduling of when we can make a delivery. If we’ve got to send a guy from here, we’ve got to allow at least six weeks for him to get a visa.” 31 These sorts of bureaucratic logjams can be particularly problematic for companies in highly regulated fields. “Our experience is primarily in defence and aerospace, which are clearly highly regulated industries requiring a lot of government hand-holding on all sides in order to make sure there is no violation of international arms restrictions, etcetera. Some of the challenges we have faced have been the slow turnaround times to security clearance and controlled goods designation processing, which are essential in terms of being able to work with American regulations through the U.S. State Department. There’s no easy answer for it because it’s bureaucracy, so there’s not a lot that can be done to speed the process of getting government support in those areas. The regulators and the security apparatus operate at their own sweet pace and sometimes that can be challenging when you’re trying to work with international clients and partners.” “In the other market, innovation is really stifled because of regulations and an unwillingness at all levels of government to be open to innovation.” Another participant, a manufacturer, was able to demonstrate how the regulatory burden impacts the country’s competitiveness. “We operate in two distinct areas, one is heavily regulated and the other is not. One of the things we find is that the market that is not regulated, we are able to bring a lot of cool new products to the marketplace. In the other market, innovation is really stifled because of regulations and an unwillingness at all levels of government to be open to innovation.” Harmonization or mutual recognition of each other’s regulations is a goal of modern free trade agreements, such as the anticipated Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union. But different countries can view regulations from different perspectives, as one participant illustrated. “Our product must be adapted for each market because regulations are all different. The EU is pretty good because they designed a model that works for a number of different countries. But also, they seem to be much more proactive in terms of the understanding of how you develop a product. There’s different levels of safety protection and they sense that and allow you approval at different levels. In North America, they just say ‘this is the highest level and everyone has to manufacture to this level’. My fear is that the EU is going to move to side with the U.S. (as a result of trade agreements). “One of the things the U.S. does in all of the regulatory issues is they put covenants or criteria in there that are specific for them that really makes it difficult for people to enter the market – they’re very protectionist. And secondly, once you go through the regulatory process with a product, it’s very difficult to do anything with that product. So once you get a product approved, you get a red stamp. If you want to tweak this or change this or 32 make it different to better suit the market, you have to start all over again. They make it very difficult. Canada is a little bit easier. But if you could open more performance-type criteria, A, you’d get a lot better product for the people to suit the customer’s needs, and B, you’d get much, much better gear. The product in the non-regulated market is just night and day better.” The Canada-U.S. border is a point of particular frustration. “People doing business in the U.S. assume that because they speak the same language, it’s the same country. It’s not the same country. The first thing you bump into is that 49th parallel. Now, the American politicians say it’s the longest undefended border in the world. It isn’t. It’s the most viciously defended border that I ever cross. Turning it around, people coming into Canada face exactly the same thing.” A Vancouver participant provided a more concrete example: “Trade shows in Canada, for the most part Canada Customs goes out of their way to facilitate U.S. exhibitors to bring up their displays and materials and that kind of stuff. But for the Americans who come up here, when they try to ship their booths back, it’s terrible. They treat it like any other commercial shipment and it acts like a barrier for Canadians to have trade shows.” “We need to come up with some sort of pass like Nexus, something that allows you to go to those trade shows,” added another participant. “I know that I don’t go across the border for trade shows anymore because of that. But something that says that, okay, x-number of employees you’re allowed to do x-number of trade shows per year…come up with the criteria.” Improving regulatory harmonization between Canada and the U.S. is important for facilitating international trade, but improving regulatory harmonization within Canada is just as important. A number of roundtable participants acknowledged that the work the Canadian and American governments are doing through the Beyond the Border Action Plan and the Regulatory Cooperation Council Action Plan is important and, if successful, should help to address some of the major border challenges. However, new issues continue to emerge such as a Congressional effort to impose a fee on goods crossing the U.S. border from west coast Canadian ports to compensate for the U.S. harbour maintenance tax. Improving regulatory harmonization between Canada and the U.S. is important for facilitating international trade, but improving regulatory harmonization within Canada is just as important. Overlapping layers of federal and provincial regulations are a longstanding complaint of SMEs. Sometimes different departments of the same government or different pieces of legislation at the same level of government can create regulatory incoherence as well, as another participant explained. 33 “The thing that drives me nuts is when it’s within Canada, pure Canadian jurisdiction. I’ll give you an example. In terms of having personnel qualified and cleared to work on secure materials, if it’s part of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, then they have to be cleared for controlled goods handling in Canada. That’s a completely separate clearance process than getting their security clearance which enables them to see secret information of a weapons system. It’s exactly the same set of checks: do you have a criminal record, are you a real person, where did you come from? All that information, fingerprinting. Exactly the same checks, administered by the same government department, but we have to go through it twice for every person. And that’s inside Canadian regulation. That’s crazy. It costs us time and money, mostly time, waiting to get these approvals before we can put a brand new guy we hired on the team to work.” One common problem of government programs is that they suffer from a lack of predictability and sometimes exist only at the whim of the government of the day. Regulations are not the only area where inconsistency between different levels of government can be problematic. A number of provincial governments have established international trade assistance programs or agencies. In fact, some of them were highlighted in our roundtables as being very effective and forward-looking. But well-intended trade assistance programs at both levels of government can end up working at cross-purposes. Not only do provincial trade initiatives add to the confusing array of programs that SMEs must try to make sense of, but they also create confusion in international markets, an issue well documented in a recent report on commercial diplomacy by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.7 If there is a silver lining to this muddle of provincial programs, it is that there may be some good ideas that could be emulated at the national level. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to analyze any of them at this time, what we heard from roundtable participants certainly suggests that may be the case and it is something that will be explored a little further in this project’s final report. One common problem of government programs is that they suffer from a lack of predictability and sometimes exist only at the whim of the government of the day. We heard several examples during our roundtables of situations where a program’s criteria were changed abruptly or the program’s deliverables differed considerably from the expectations. Changes in government policy can also pose problems, as described by one participant whose company, a private sector education provider, recently acquired another firm. 7The Canadian Chamber of Commerce. Turning it Around: How to Restore Canada’s Trade Success. Ottawa: May 2014. 34 “They (the recently acquired firm) had a variety of interesting programs, one of which was created at the behest of Citizenship and Immigration Canada and works with various corporations as well as government divisions. Really interesting stuff and I give credit to the previous owner for that. But the previous owner had also built the business with a lot of expectations for Mexico. And when the visa requirements were changed for Mexico, his business tanked. Now, good for me, I could buy it cheap. But, you know, what kind of a model is that for taking seriously the support for private education?” While our participants have provided plenty of examples of bureaucratic frustration – more than we have space for in this report – it would be unfair to end this report on such a note. Behind the regulations and processes are many well-meaning public servants who honestly do their best to assist their business clients. One of those people is a food safety inspector who clearly sees the larger picture, as described by one of our roundtable participants. “After my first shipment, a food inspector came to my warehouse to check the products for labelling. He has since become a bit of a mentor to me. Whenever I’m thinking of doing something, I check with him and ask him what I should know. If he doesn’t know, he forwards my email to someone else or directs me to another website.” In an ideal world, that’s the level of customer-focused service that all government agencies would provide to all businesses. Behind the regulations and processes are many well-meaning public servants who honestly do their best to assist their business clients. 35 36 Conclusions and next steps 9 As mentioned at the outset, the purpose of this paper is not to propose recommendations but rather to reflect the views and experiences shared with us during our cross-country roundtable consultations. What becomes apparent is that the government’s goal of almost doubling the number of SMEs doing business in emerging markets in the next five years, while laudable, may be difficult to achieve. The examples of our roundtable participants illustrate that SMEs, particularly smaller businesses, face significant obstacles and challenges when doing business internationally – even with our most established trading partners. Yet these are businesses that have taken the plunge and are succeeding internationally, at least to some degree. For those many small business owners who wonder why they should bother going international, the experiences and frustrations shared by our roundtable participants certainly will not convince them. Expanding into international markets is very risky for small firms, especially so when expanding into developing markets. A recent report from the Conference Board of Canada pointed out both the risks and the rewards for SMEs of doing business in fast-growing markets. “Smaller players need to overcome policy barriers, rapidly gain knowledge about local markets, and find trusted local partners—and do so with relatively fewer resources and less talent compared with larger companies,” it noted.8 “Smaller players need to overcome policy barriers, rapidly gain knowledge about local markets, and find trusted local partners—and do so with relatively fewer resources and less talent compared with larger companies.” Yet the opportunities are real. If the target for SME trade performance is to be achieved, the resources of the Trade Commissioner Service and other government agencies will need to be expanded and improved – not something that will be easy to accomplish in today’s fiscal environment. CGA-Canada is considering what we heard at the roundtables in combination with the results of a national survey of businesses, consultations with CGAs who advise small businesses, and advice from subject matter experts. We will report on those deliberations and offer our conclusions later this year. 8Sui, Sui and Danielle Goldfarb. Not For Beginners: Should SMEs Go to Fast-Growth Markets? Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada, 2014. 37 38 Appendix A: Roundtable Dates, Locations and Partners 10 Mississauga – November 19, 2013 Mississauga Board of Trade Ottawa – December 11, 2013 West Ottawa Board of Trade Invest Ottawa Saskatoon – February 18, 2014 Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce Halifax – March 4, 2014 Halifax Chamber of Commerce Nova Scotia Community College Vancouver – April 25, 2014 Vancouver Board of Trade Quebec – May 27, 2014 Québec International All roundtables moderated by Carole Presseault. 39 40 Appendix B: Roundtable Participant List Gail Adams Halifax Chamber of Commerce Lisa Carolglanian Dorazio CanAmeri Consulting Inc. Omar Allam World Trade Advisors Yves Drouin Jyga Technologies Alexandra Aluja Cannan Group Tamara Dundas Wiegers Financial and Benefits Tracy Arno Essence Recruitment Andrew Edwards Contingent Workforce Solutions Stewart Bain BCI John Ellis DB Schenker Glenda Barrett Nova Scotia Community College Daniel Fay BrenDaniel Productions Corp. Ray Barton Enercom Canada Timucin Gokdemir Polipark Inc. Alex Beraskow myRENO411 Ray Graves Saskatoon Boiler Guillaume Blanchard Quebec International Luz Gomez-Lozada Business Development and Field Marketing Specialist Don Bureaux Nova Scotia Community College Stéphane Clément Jyga Technologies Darrell Cochrane Porter Hetu International Paul Courtney Courtney Agencies Limited Dean Dangas Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce Anne-Marie Deslauriers Medicago Mel Dhanaraj Sensei Procurement Ltd. 11 Denis Hamel Quebec Government Ned Ismail Contingent Workforce Solutions Sriram Iyer Steel Holdings Corporation Ltd. Greg Johnson RBR Global Kevin A. Johnson Lette LLP Nicholas Kokkastamapoulos Hanlon Centre for International Business Studies Joanne Lalonde Hayes More Time Moms 41 Csaba Laszlo Laszlo C. M. D. Ltd. Benoit K. Simard BMO Bank of Montreal Khalid J. Latif Ainaf International Inc. Cesar Sanguinetti C & C Graphics Sheldon Leiba Mississauga Board of Trade Sonja Shan Hanlon Centre for International Business Studies Meghan Lloyd Fox Harb’r Golf Resorts & Spa Ken MacQueen IVEK International Education, Inc. Ravi Maithel Clevor Technologies Syd Martin Affimex Custom and Trade Services Margarita Motta Quebec International Janet Mtanos Q Innovative Foods/ Q Foods Canada Austin Nairn Vancouver Board of Trade Raj Nayak e-Inc. Ben Neaves Climate Technical Gear Dennis Orellana Flight Centre Business Travel – Canada Jim Pyra Atlantis Systems Corp. Ali Jawad Rana Solsnet Solutions Network Darren Reeves Interpro Forest Products Darrell Schneider Saskatchewan Food Processors Association 42 Richard Smith Aversan Inc. Lu Shao Pivotal Scientific Kent Smith-Windsor Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce Pat Snelling Allan & Snelling LLP Jean-Sylvain Sormany Snowed in Studios José Torio International Sales Consultant Emrah Tutumlu Mapleville Import Export Sab Ventola Pleora Technologies Joe Vidal Bioriginal Food & Science Corp. Joshua Wang Aschroft Terminal Gord Wilson WorldReach Software