Press - Ina Dittke & Associates

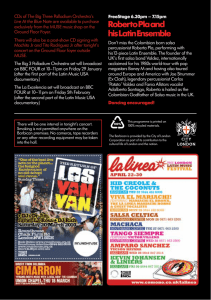

advertisement

The Big 3 Palladium Orchestra Barbican, London Robin Denselow Wednesday 27 January 2010 In New York in the 50s, there was one place where Latin music fans just had to go: the Palladium Ballroom on West 53rd Street and Broadway. There, they could dance to the mambo, cha cha and rumba, and listen to the Mambo Kings – Machito, Tito Puente and Tito Rodríguez – the three legendary bandleaders who transformed the US music scene. The Palladium is long gone, but the big-band music that made it famous is back, -courtesy of the Big 3 Palladium Orchestra, featuring the timbale-playing sons of both Machito and Rodríguez. This show was an intriguing curtain-raiser for the new BBC4 series Latin Music USA, but didn't have quite the impact it deserved, thanks to the opening act. The contemporary New York salsa band La Excelencia were slick, but played for so long that the headliners had to curtail their own performance. When the Palladium Orchestra finally took to the stage, dominated by percussion and an eight-piece brass section, it was Tito Rodríguez Jr who first acted as band leader. He lovingly revived his father's old compositions, showed off his percussion skills on El Mundo de las Locas, and brought on the great trombone player Jimmy Bosch for an impressive solo. This was grand, rhythmic easy-going dance music, but it took the second band leader, Larry Harlow, to introduce a real sense of excitement. A pianist and composer who played with all three Mambo Kings before working with salsa heroes, the Fania All-Stars, he matched an edgy, attacking approach with a fine improvised solos. Finally, Machito Jr took over, but by now the show had over-run, and he didn't even have time for his father's hit Babarabatibiri. Surely this never -happened at the Palladium. QUE PASA? The Big Three, part two By Robert Dominguez, March 4, 2004 More than 50 years after the most famous rivalry in Latin music began, a second generation of bandleaders are revisiting the songs - and battles - of their fathers. The orchestras of Tito Puente, Frank (Machito) Grillo or Tito Rodriguez filled the room with heat back when the Palladium Ballroom on 53rd St. and Broadway was the epicenter of the Latin dance scene. But whenever any two of those bands were booked on the same night - and especially on those occasions when all three orchestras shared the bill - the Palladium crowd knew it was in for a special evening. Known as 'The Big Three', Puente, Rodriguez and Grillo enjoyed a friendly rivalry for clubgoers' hearts and wallets. Playing the Palladium on the same night meant an all-out battle of the bands. "My father told me that he always preferred it when both Titos were playing on the same bill as him, rather than just one of them," says Mario Grillo, Machito's son. "Because that meant they would beat up on each other and be too exhausted to compete with his band. Machito knew that if he went one-on-one with either of them, he was in for a battle royale." The Big Three aren't around anymore, but their decades-old competition was recently brought back to life. Three years ago, Grillo, a bandleader like his father joined Toto Puente Jr and Tito Rodriguez Jr - who also lead their own orchestras - to form the Big Three Palladium Orchestra. The 23-piece outfit, featuring many veteran musicians who performed with the original bands, is at the Blue Note in Greenwich Village through Sunday. During each set, Grillo, Puente Jr and Rodriguez Jr take turns leading the band, which used their fathers' original arrangements. "We play the music as authentically as we can." Says Grillo. "Older people who got the chance to see our fathers will enjoy it, and those who didn't can experience it for the first time." "Just as authentic", adds Grillo "will be the new rivalry among the sons." "Like our fathers, we take the spirit of competition seriously, but there's a lot of love and respect there too," says Grillo. "We'll kill each other on the bandstand and then go out and have something to eat." Sons of mambo mania Big 3 Palladium Orchestra recalls energy of an era. W. Kim Herron, Detroit Metro Times, 9th July 2003 It was no place for slobs, slouches or squares. There'd be hundreds, maybe a thousand, fancy steppers and hip shakers, dressed to the nines, gyrating on the wood floor of the converted dance studio. On any given night, Sammy, Tony, Marlon, Lena or Marlene (as in Davis Jr., Bennett, Brando, Horne, Dietrich) might be hanging out. It was a had-to-be-there place like the Whiskey A Go-Go in the 60s, or Studio 54 in the 70s or that archetypal space that Prince sang about the 80s with black, white, Puerto Rican, everybody just a-freakin. It was the epicenter of mambo mania, a populist embodiment of one of the great fusion musics of all time, Latin jazz. It was New York's Palladium Ballroom, starting in the late 40s, and burning through the next decade and then some. "What I remember about the Palladium as if I were standing in there right now is the quality of the sound," says Mario Grillo, who debuted there at age 5, slamming at the timbales under the watchful eye of his dad, the bandleader and Latin jazz giant Machito. "It was a very acoustic room, and music sounded great in there. And packed, packed with people." Forty years later Grillo is revisiting and reinvigorating that era as a co-leader of the Big 3 Palladium Orchestra, a super ghost-band whose helm he shares with the sons of the two other top late Palladium bandleaders, Tito Puente Jr. and Tito Rodrguez Jr. "It was a dream you dig it? like Martin Luther King had a dream," says Grillo, who speaks over the phone with the energized rat-a-tat poetry of Latin jazz jive. "I woke up in the middle of the night, and said, Shit, wouldn't it be great if I could make a band and pay tribute to our fathers and get the other sons involved with me?" So was born the Big 3 Palladium Orchestra. Rodrguez died in the 70s and Machito in the 80s, and their sons, in their late 40s, have been continuing the family franchises for years. Puente died in 2000 and his son, who'd been active in contemporary Latin dance music, has taken up his father's music as well. (Puente Jr. has also opened some dates for the White Stripes of late.) For all the history it taps into, the 22-piece Big 3 Palladium hasn't exactly caught the imagination of the big labels. "We can't get a record deal, we can't even get arrested. I ran across 47th Street naked, the cops didn't even look at me," says Grillo, bemoaning the lack of interest. Yet Big 3 Palladium is a dream band for the Concert of Colors, which has as its raison d'aitre to bring diverse audiences together around the diverse musics of the world. Underlying the varied offerings, there's always a lesson in the ability of musics to speak universally, whether the lyrics are in English or Yoruba; and underlying that there's often a tangled series of connections that make the various musics less distant than they might seem from one another. Cuban music, for instance, is deeply rooted in the music of slaves brought from Africa, and exported Afro-Cuban styles are in turn at the root of soukous, the influential Zairean pop style. Some musicologists hear the echo of the fundamental Afro-Cuban beat, the clave, in the chunk-a-chunkchunk, chunk-chunk of Bo Diddley's archetypal rock guitar. Others cite the Cuban influences on such classical composers as Bizet, Ravel and Debussy. And Latin jazz turns out to be something other than the simple marriage of two musics as the name might imply. Rather its story is one of multiple Mexican, Cuban and other Caribbean influences on jazz at its very roots in turn-of-the-century New Orleans; then repeated musical interchanges follow until the grand era of the mambo and beyond. That's the kind of vision being popularized in recent years with a rising stature for Latin jazz. You could see that, for instance, in last year's Smithsonian exhibit and the accompanying bilingual book Latin Jazz: The Perfect Combination by Raul Fernandez. Fernandez gives an almost breathless overview of his subject as he cuts back and forth from New York to Havana, from Duke Ellington to Xavier Cugat, and up through such young artists as saxophonists David Sanchez and Jane Bunnett. But from the late 1930s until his death, Cuban-born Frank Grillo, better known as Machito, is rarely far from the heart of the narrative, usually along with his brother-in-law and longtime musical director Mario Bauza. In the 1940s, Machito and his Afro-Cubans, writes Fernandez, became the cauldron for a new musical brew. Seemingly everyone in jazz had a taste, and cats like Dizzy Gillespie and Stan Kenton got totally juiced on what was dubbed cubop. Meanwhile, for the dance crowd, Machito and his contemporaries served up the mambo, which became a bona fide national dance craze with the Palladium as the hippest asylum. Alongside Machito, younger bands led by Puente and Rodriguez established themselves as his musical peers and competitors. "They'd headline individual nights, and for special occasions, they'd appear in temas of two or three. Each group had its own sound," Grillo says. "Machito's band was the blueprint. Puente, whose main instrument was the timbales, fittingly, had a more percussive sound as a whole; born stateside rather than an immigrant, Puente brought an urban edge to things. Rodriguez, also of the US born generation, was a suave singer who crafted a lusher sound to wrap around his voice. But by the same token, he wanted very swinging arrangements behind him so he could compete with Tito Puente and Machito," says Grillo. Grillo recalls his father's explanation of ehat it was like to play with the two Titos in battles of the bands; "He told me that when I had the two of them together, it was easy. And he said Tito would beat the crap out of Tito and Tito would beat the crap out of Tito and by the time they got to me, they were easy to take. But if I played with them head to head, I knew that I was in for a battle royal." The attraction of the current three headed band isn't just the leaders and the crack band of Latin Jazz veterans, but the cache of original instrumental scores from the original bands. "I'm talking about arrangements that are done in India ink, you know, which are 40, 50, 60 years old. One of the things we've had to do is recopy a lot of the music because it's brittle, you can't be taking it out and exposing it to the elements. It falls apart on you. And there's a lot of it," Grillo adds: "Tito Puente recorded 118 albums; Machito recorded 85 albums; Tito Rodriguez recorded about 60, so between us we have almost 300 albums, which means we have 3,000 arrangements." Not that they carry all of them at any one time, but they'll bring enough, he promises: "tell people when you come to see this band, you better wear an asbestos jacket, baby, because we gonna burn you, yeah. I ain't playin' around. It's fire on top of fire on top of fire." Offspring lead thrilling tribute to Latin legends By Tom Moon Monday 15 July 2003 Inquirer Music Critic The Big 3 Palladium Orchestra, which electrified the Kimmel Center Friday night as part of the weekend long Fiesta Latina, is a repertory ensemble, the salsa equivalent of the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra. Its mission is to celebrate the music of three beloved Latin bandleaders - Tito Puente, Machito, Tito Rodriguez - who made New York's Palladium a hot spot in the 19505 and '60s. Though the orchestra is fronted by the offspring of' the three legends - timbale players of varying skill - the real attraction was the band, a collection of top-shelf recording artists, including saxophonist/flutist Mario Rivera and pianist Oscar Hernandez. For more than an hour, this 16-piece dynamo punched out crisp, incredibly exciting music for dancing that enchanted the small, and mostly seated, Verizon Hall crowd . It honored the rhythmic rituals of mambo and cha-cha while adding smart contemporary inflections, and its energy suggested that this music can become vibrant - and profoundly new - with reexamination. Each leader got his own set. Tito Puente Jr., who looks remarkably like his father Circa 1958, devoted his segment to showbiz shtick, but lacked his dad's redeeming percussion virtuosity . He led the crowd through a version of "Oye Como Va," the Puente Sr. tune that was a hit for Santana; stuck his tongue out with glee when he spotted a camera; and seemed more interested in clowning then playing. Tito Rodriguez Jr's homage went deeper. It included a gorgeous bolero sung by Sammy Gonzalez and several brisk jams - including one that inspired a fluttering Rivera masterpiece of charanga flute. During the part led by Machito's son Mario Grillo, the band chased the uncompromising swing that distinguished the father's groups. The arrangements, many exact transcriptions of the originals, featured elaborate stop-time exchanges between the brass and the saxophone sections, and solos that caught the romantic ardor of Latin melody while subtly injecting hints of jazz harmony. Incendiary jazz takes the chill out of June By Howard Reich, June 15 2003 Chicago Tribune Arts Critic Considering the temperature was low, Saturday night's instalment of Ravinia's Jazz in June series did not have a lot going for it. Except for some of the most accomplished Latin jazz artists on the planet. To note that the third night of Jazz in June was its best would be an extreme understatement. This was one of the most viscerally exciting performances in the decade-plus history of Ravinia's jazz mini-fest and a reminder of the remarkable artistic level that the Highland Park soiree can achieve. In a three-attraction evening that had no weak points, the most thrilling music by far came from a sensational, relatively new band, improbably called the Big 3 Palladium Orchestra. One might not expect very much from any ensemble that has been playing for barely two years and is directed by not one but three leaders. Yet judging by Saturday night's incendiary (though technically disciplined) performance, the Big 3 Palladium Orchestra already may rank as the most brilliant large Latin jazz ensemble this side of Havana. The fanciful title refers to New York's fabled Palladium Ballroom, which from the mid-1940s to the mid-'60s was a nexus for Afro-Caribbean music in the United States. Machito, Tito Puente and Tito Rodriguez were the "Big Three" bandleaders who gave the Palladium a large measure of its glory , and their gifted sons recently joined forces to create an unusual ensemble specializing in repertoire of each of the three jazz legends. If this sounds like a formula for disaster - with three competing egos pushing different songbooks and agendas - the opposite proved to be the case. For Mario Grillo, (Machito's son), Tito Rodriguez Jr. and Tito Puente Jr. have staffed this ensemble with Latin dance-band veterans who can dispatch this repertoire more authoritatively than any younger group of musicians might hope to do. Moreover, the idioms that this band explores - from the "Cubop" orchestral showpieces of Machito to the medium-tempo mambo classics of Rodriguez to the orgiastic dance rhythms of Puente probably have not been so authentically expressed since the original bandleaders themselves were in their heyday. From the outset, Grillo established the technical prowess, stylistic credibility and creative vitality of this group, for this ensemble (conceived by Grillo) addresses this music in fundamentally different ways than bands less steeped in the tradition. For starters, Grillo and friends took pains to lay bare the layers of rhythm on which this music is built. Piano and percussion laid down the multiple "clave" patterns that more often than not these days are buried in a blur of orchestral sound. With Grillo revisiting Machito's repertoire, the rhythmic impulses of this music rightly were placed at the forefront, just as it is to this day in ensembles in Cuba, where Machito grew up (he was born Frank Raul Grillo). And the tempos that the younger Grillo chose - gently but inexorably pushing forward - were ideally suited to this music. When Rodriguez Jr. took over, the very character of the band seemed to change, with great brass choirs and florid, call-and-response vocals suddenly taking prominence. To hear so many virtuoso instrumentalists and vocalists producing so much contrapuntal sound - all of it propelled by extraordinarily seductive backbeats - was to savor the splendor of this band. "If the young Puente enjoys re-creating his father's antics at timbales, the audience clearly welcomed the chance to revisit the spirit of the music of "El Rey" ("The King," as the elder Puente was known). Yet this was no nostalgia show, for the band once again reaffirmed the perpetual freshness and creative possibility of this music.