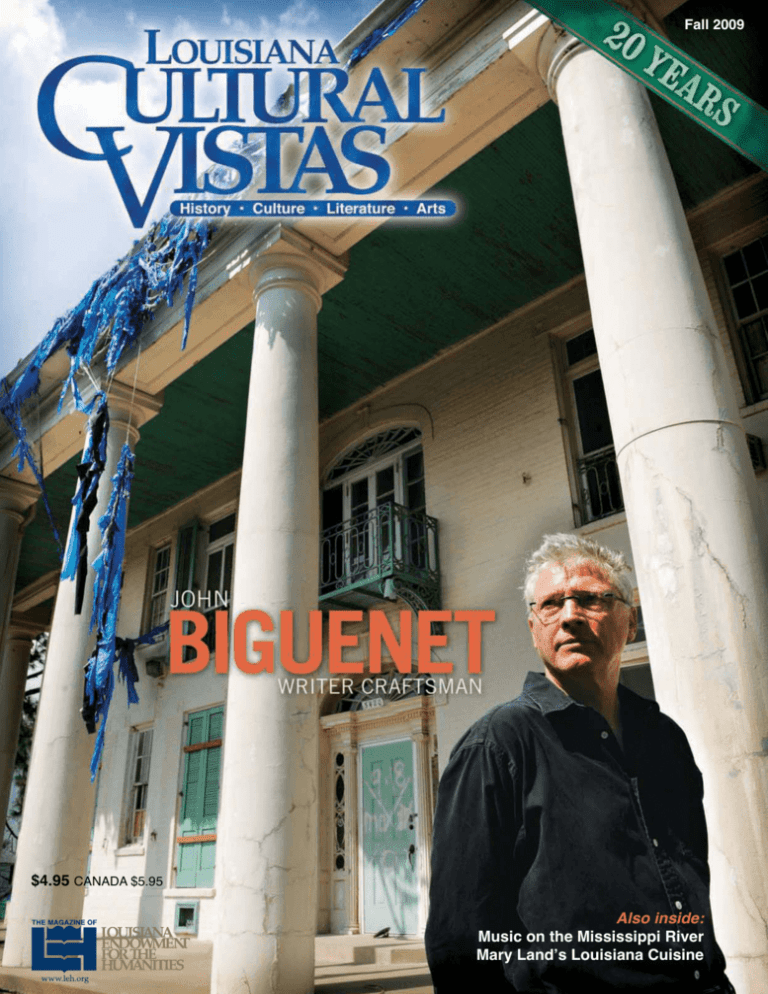

john biguenet

advertisement

Fall 2009 $4.95 CANADA $5.95 Also inside: Music on the Mississippi River Mary Land’s Louisiana Cuisine JOHN BIGUENET PHOTO BY CHERYL GERBER WRITER CRAFTSMAN BY KATHY FINN 10 I n a society whose artistic and creative endeavors focus largely on matters of the moment, fiction writers with an intuitive sense of history are rare. Contemporary American stories and dramas tend to be torn-from-the-headlines affairs that depict familiar characters, often in predictable conflicts. Occasionally, though, a writer emerges who is not afflicted with historical amnesia; who is equally at home in the present and the deep past; who offers his readers startling characters and situations they haven’t seen before. John Biguenet, an O. Henry Award-winning writer and professor of English at Loyola University, grew up in New Orleans and sometimes sets his fiction in contemporary Louisiana. But his stories also range across continents and centuries, and frequently employ fantastic conventions along the way. His central character may be an itinerant torturer plying his trade in Medieval Europe; a middle-aged American facing a moral test while visiting Germany after World War II; or a young engineer only mildly fazed by toads raining from the sky in post-colonial Latin America. “John in no way fits any kind of stereotype of what you’d consider a Southern or Louisiana writer,” says author Tim Gautreaux, a fellow O. Henry Award-winner who has set many of his own stories and novels in his native Louisiana. “I CAN SPEND AN ENTIRE DAY ON ONE PARAGRAPH.” —JOHN BIGUENET Known for his down-to-earth characters and homey wit, Gautreaux says he’d be inclined to term Biguenet “a cardcarrying intellectual” were it not for the fact that “he’s very affable, earnest and just a nice guy.” Biguenet all but ensured he would not be pigeonholed as a regional American writer with the publication in 2001 of his short story collection, The Torturer’s Apprentice (Ecco/HarperCollins). A few of the stories in the book use Louisiana as a backdrop, but most unfold in other parts of the world, real or imagined. The works helped solidify his reputation as a meticulous, intellectually rigorous writer with a fearless imagination. In one of the collection’s best-known stories, “The Vulgar Soul,” a young man devoid of religious belief develops a stigmata. As the five bleeding wounds of the Crucifixion gradually appear on his body, believers gather to see and touch him. He shuns the awe and attention of his new followers, but when the wounds begin to heal he confesses: “ ... the whole time people were whispering ‘miracle, miracle,’ I never once pretended at something I didn’t feel, didn’t believe. And now that it’s all over—I know it’s crazy— now I feel like I’m living some kind of lie.” The “Vulgar Soul,” which he later adapted for the stage, and other stories brought Biguenet wide exposure. His fiction and essays appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, Esquire, Playboy, Granta (U.K.), Zoetrope and various anthologies, including The Best American Mystery Stories and Best Music Writing. His work has been published in the United Kingdom and translated into several languages. His repertoire also includes four books he edited or co-edited on contemporary international fiction and on the theory of translation. Fall 2009/LOUISIANA CULTURAL VISTAS 11 A NEW ORLEANS BOYHOOD Clear-eyed and bespectacled, with a gentle manner and a sweep of silvery hair, Biguenet, 60, fits his title: the Robert Hunter Distinguished Professor at Loyola. When he’s not in a classroom, he’s the picture of an artist driven to write. Ten minutes alone with a cup of coffee is an opportunity to begin a new story or rethink a character. A two-hour block might allow him to finish a chapter—or re-write a single sentence over and over. “I can spend an entire day on one paragraph,” he confesses. He attributes his fastidiousness to his father who, after years in the U.S. Merchant Marine, worked as a carpenter. “His enormous respect for knowing the craft of carpentry had a huge influence on me,” Biguenet says. “He often said that a carpenter with enough wood and enough nails ought to be able to build and fill an entire house. So I approach writing that way. I ought to know how to translate, how to write poetry, fiction, plays. It’s not enough simply to get something on stage, I need to really interested in foreign languages, and then in language itself.” When Loyola University offered Biguenet a full scholarship, his future began to crystallize. While working toward an English degree at Loyola, he threw himself into writing and also met the woman who would become his wife. Marsha, then a student from Philadelphia, happened by as Biguenet was giving an anti-war poetry reading on the steps of the university library. She introduced herself, and the pair joined in a protest march. “That was our first date,” he says. The two married and later headed for the University of Arkansas, which had offered Biguenet a graduate fellowship. He earned a master of fine arts degree in creative writing, then became the poet in residence at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, a post he held for two years before returning to New Orleans to teach at Loyola. The couple eventually settled into the Lakeview neighborhood where they raised two children, Nicole and Jonathan. Marsha Biguenet now is principal of the lower “I THINK, IN THE END, FANTASTIC LITERATURE IS NOT ABOUT AN ESCAPE FROM REALITY, IT’S ABOUT DROPPING US MORE DEEPLY INTO A REALITY THAT WE’RE BLIND TO OR THAT WE CHOOSE TO REMAIN SILENT ABOUT.” —JOHN BIGUENET John Biguenet’s home library was largely destroyed by Katrina’s flood waters. school at Metairie Park Country Day School. understand how a play is made, and novels and short stories.” His hunger for writing was not always obvious, at least to him. While he was growing up in the Gentilly neighborhood of New Orleans, and during his years at Cor Jesu (now Brother Martin) High School, sports were his first love. The lanky boy was captain of the basketball team. He also was an avid reader, though. He enjoyed writing poetry and had an appreciation for languages. During summers, he and his younger brother and sister would visit his mother’s Italian relatives in Brooklyn, N.Y. “Brooklyn, then, was totally cosmopolitan,” he says. “We would hear Italian and Greek, Arabic and Yiddish ... there was kind of this soup of languages I didn’t understand, but they sounded so musical. I think that’s when I began to be 12 LOUISIANA ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES\Fall 2009 EUROPE, LATIN AMERICA As Biguenet continued to teach and write, his literary horizons expanded. He began to tire of contemporary American fiction and gradually focused more on European writers of the 19th century—Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevski, Jane Austen. The short stories of Anton Chekhov still top his most-admired list. “I never read a story by Chekhov without learning something. He’s been an enormous influence.” He also found kindred spirits in Latin America, in such writers as Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar and Jorge Luis Borges. He met and talked with Borges late in the Argentine writer’s life and says they shared similar feelings about “the persistence of the past,” a sense of being part of a 13 PHOTO BY CHERYL GERBER continuum that reaches from the past into the future. Biguenet’s ancestors, whom he has traced to northeastern France, first set foot in New Orleans some 250 years ago. “I walk in the French Quarter and (I know) my relatives have walked those streets for hundreds of years. I don’t think many Americans have that same experience of rootedness,” he says. Another connection he felt with Latin American writers stemmed from their use of fantasy. Biguenet found the “magical realism” honed by García Márquez and others liberating. “I think, in the end, fantastic literature is not about an escape from reality, it’s about dropping us more deeply into a reality that we’re blind to or that we choose to remain silent about,” he says. An element of fantasy he has found particularly helpful in his own work is the ghost. He used the device to poignant effect in a story entitled “Fatherhood.” In the story, a young married couple grieves over the woman’s recent miscarried pregnancy until the ghost of a young child appears in the room they had prepared as a nursery. “The man looked upon his wife and child, and he felt something inside click open—as if a secret lock had been disengaged by small hands that, cupping his heart above and below, had twisted it first one way and then another.” New Orleans, taking the young Biguenet along. While he delighted in discovering the world of the open water, his father made sure he also understood the cold realities. During one trip the boy asked why the croakers they were piling up in the ice chest were making so much noise. His father answered: “They’re calling for their mama, but she can’t hear them.” Chilling, perhaps, but Biguenet got the message: Sentimentality has no place on the water. Biguenet recounted a version of the incident in Oyster. His fishing experiences also had a clear bearing on another of his stories, entitled “And Never Come Up.” The narrator in the work relates a grisly but somewhat humorous tale about a fishing trip with his father where circumstances go awry and the two are stranded overnight on the water. In relating his story, the narrator frequently digresses into anecdotes about his dad. “My father was a real sailor, all right ... he told me one night when he was good and drunk that the best advice he’d gotten in a dozen years at sea was from an old sailor: ‘Never learn to swim—it only prolongs the drowning.’ I remember when he told me he took another swig of bourbon and then, with one eye open, swore, ‘But goddamn it, I already knew how to swim.’“ “I NEVER READ A STORY BY CHEKHOV WITHOUT LEARNING SOMETHING. HE’S BEEN AN ENORMOUS INFLUENCE.” —JOHN BIGUENET HOME AGAIN After publishing the stories of The Torturer’s Apprentice, Biguenet seemed to refocus on his roots. In 2002, HarperCollins published his first novel, Oyster, an earthy tale of murder and intrigue among feuding families that plays out in the marshlands of South Louisiana. The novel hearkened to Biguenet’s past. His father and grandfather often fished the lakes and marshes south of DELUGE The dangers of water confronted Biguenet in a completely unexpected way on Aug. 30, 2005. It was the day after Hurricane Katrina sideswiped New Orleans. Just as the city was sighing its relief, water began gushing in. Biguenet’s home was but one casualty of the deluge that drowned some 1,500 people and left tens of thousands homeless. Forced to live outside the city for weeks, the writer began chronicling for The New York Times the devastation wrought by the failures of government- Eighty percent of New Orleans was flooded following federal levee failures in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. 14 LOUISIANA ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES\Fall 2009 PHOTO BY JOHN B. BARROIS designed flood protection systems. “He was personally affected in a very strong way,” says longtime friend and novelist Valerie Martin, author of several short-story collections and nine novels. Martin, who grew up in New Orleans and taught at two local universities before relocating to the Northeast, says Biguenet’s ability to express “what it felt like to be inside the process of trying to put your life back together” made his New York Times chronicles “some of the best stuff I read after the hurricane.” In some ways, Biguenet may have been better prepared than others to face the lessons of Katrina. His own history and philosophy have made him skeptical, maybe even cynical, about the idea that individuals command their own destiny. “We want to think that we’re all free agents, individuals, and able to become all that we want to be. The Europeans have been taught over and over again that that’s not the way life operates. Things happen that are outside your control,” he says. “Here in New Orleans we learned it over and over again, as the city burned to the ground, plagues hit the city, civil war, reconstruction, the collapse of our levees. We know that it doesn’t make any difference how hard you work, how good a person you are. Things are going to happen—they’ll destroy your life, nobody will take responsibility and you’re on your own to fix it.” When Biguenet and his wife returned to New Orleans from their post-Katrina exile, he continued to write during any time he could squeeze between teaching and the tedious work of repairing their home. Before the storm he had started a new play, but the disaster and his anger over its cause spun him in a different direction. He laid plans for a series of dramas set in New Orleans during the weeks and months after the flood. In 2007, Southern Repertory Theatre in New Orleans presented Biguenet’s Rising Water. The play, in which a middle-aged married couple are stranded by the flood on the roof of their home and forced to face their destiny, became the biggest seller in the theater’s history. Recently, Southern Rep debuted the second work in Biguenet’s three-play cycle. In Shotgun, racial conflict piles on top of personal loss as an African-American woman and her father find themselves living under the same roof as a white man and his son a few months after the flood. Scenes from the 2007 premiere of John Biguenet’s play Rising Water: A New Orleans Love Story, starring Danny Bowen and Cristine McMurdo-Wallis at New Orleans’ Southern Rep Theatre. Fall 2009/LOUISIANA CULTURAL VISTAS 15 Rus Blackwell and Donna Duplantier portray New Orleanians in the months following Katrina in Shotgun, a play by John Biguenet that premiered at Southern Rep Theatre in May 2009. PHOTO BY JOHN B. BARROIS Because of the racial conflicts involved, Biguenet felt strongly that Shotgun should have an African-American director. Southern Rep brought in Valerie Curtis-Newton, who teaches directing at the University of Washington School of Drama and is artistic director of The Hansberry Project in Seattle. “In many ways we mirrored the play, a white man working with a black woman, trying to uncover the truth of these characters,” Curtis-Newton says. Drawing a parallel with iconic African-American playwright August Wilson, who created a history cycle to explore the “psychic wound of slavery,” she says: “I think John’s exploring the psychic wound of Katrina and the levees breaking. I think there’s a tremendous accomplishment in even beginning to undertake that.” Writer Martin was not surprised that Biguenet delved into racial issues in Shotgun. A “preoccupation with race relations” characterizes New Orleans writers, she says. Martin undertook her own examination of slavery a few years ago in a novel entitled Property. She says she was working on the book at the same time that Biguenet was writing a short story called My Slave. “That story is a really brief but sharp look at slavery and what the mentality of the (slave) owner had to be,” she says. “John has a real speculative imagination; he considers all the time what it’s like to be someone appalling.” Biguenet used a similar approach in his story The Torturer’s Apprentice, which Martin describes as exploring “the mentality of a torturer and the idea of torture as art.” “I THINK JOHN’S EXPLORING THE PSYCHIC WOUND OF KATRINA AND THE LEVEES BREAKING. I THINK THERE’S A TREMENDOUS ACCOMPLISHMENT IN EVEN BEGINNING TO UNDERTAKE THAT.” —DIRECTOR VALERIE CURTIS-NEWTON PHOTO BY JOHN B. BARROIS In the work, an experienced medieval torturer, Guillem, teaches a young man how to administer intricate physical punishments to persons declared guilty of heresy and other offenses. “Annoyed at first by the boy’s squeamishness, Guillem came to appreciate his apprentice’s gentleness. He had often sensed that cruelty was the enemy of the torturer. In fact, cruelty seemed to him a kind of arrogance that a professional would disdain; it was an intoxicant of amateurs.” Actors Lance E. Nichols and Donna Duplantier were among cast members of the premiere of John Biguenet’s Shotgun at Southern Rep Theatre, directed by Valerie Curtis-Newton. 16 LOUISIANA ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES\Fall 2009 At its most basic level, The Torturer’s Apprentice explores the nature of a parent-child relationship and efforts by the parent figure to prepare the child for life’s harsh realities. Biguenet has touched on the theme more than once in his work, in part because of his own strong feelings about it. “We persist in offering children a sentimental view of the world, and I don’t think they need it,” he says. “I don’t think it’s particularly useful to lie to them about the way the world works.” One young writer among the many who have benefited from Biguenet’s own “parenting” skills is New Orleans author Joshua Clark. In 2003, Clark included Biguenet in an anthology of local writers he published, called French Quarter Fiction. He became particularly well-acquainted with Biguenet after Katrina, when they sometimes traveled together to other cities to participate in panel discussions and carry the message of what had transpired in New Orleans. “Here I was, this young guy writing short stories, and with everything he had going on, he said, ‘If you have anything you’d like me to look at, I will,’“ Clark recalls. “He gave me a lot of feedback on a story and he made it much better.” As he continues to mentor up-andcoming writers, Biguenet intends to keep articulating the impact of the 2005 disaster on New Orleans. His third play in the Katrina cycle, tentatively entitled Mold, is under way, as is a novel that addresses aspects of the tragedy he hasn’t covered in the plays. Yet another novel and more stories also are in the works. And one day when time allows, perhaps Biguenet will get another sailboat to replace the one he lost in the hurricane. “When I went out to the marina to check on it, I saw that the pilings had gotten broken in half, but all my knots held,” he says. “I thought my father would be proud of me that I tied those knots properly to the cleats.” LCV ___________________________________ Kathy Finn is a freelance writer and editor in New Orleans. She edits the theatre and performing arts magazine On Stage. For more information about John Biguenet’s books, log on to www.johnbiguenet.com. His archived columns for The New York Times about Hurricane Katrina and the federal levee failures can be read online at www.biguenet.blogs.nytimes.com/. Information about Southern Rep TheatreTheatre can be found at: www.southernrep.com. Fall 2009/LOUISIANA CULTURAL VISTAS 17