Billion Dollar Divide - Justice Policy Institute

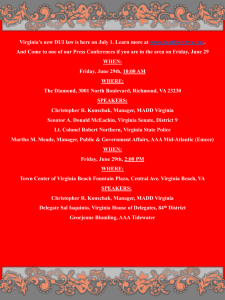

advertisement