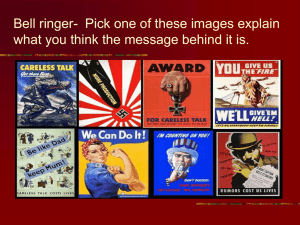

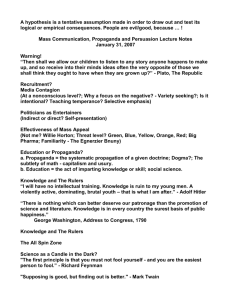

WHAT IS PROPAGANDA, AND WHAT EXACTLY IS WRONG WITH IT?

advertisement