Part 3

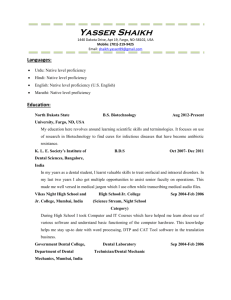

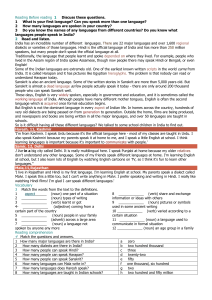

advertisement