Icon - University of Texas Libraries

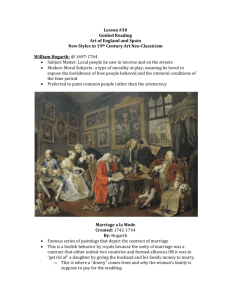

advertisement