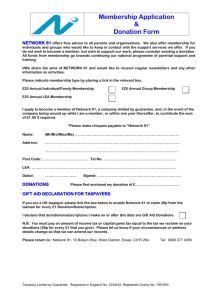

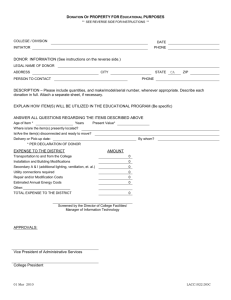

DONATIONS - Louisiana State University

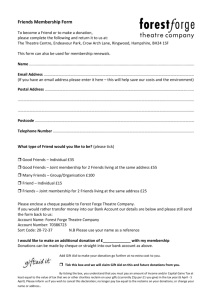

advertisement