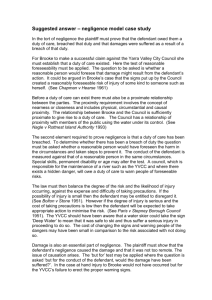

Negligence duty cases

advertisement