contracts - Nova Scotia Barristers' Society

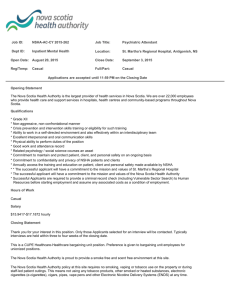

advertisement