the Teacher's Guide - Vancouver Holocaust Education

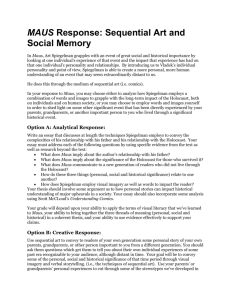

advertisement