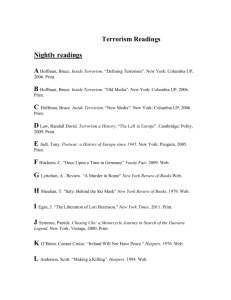

Bachelor Thesis - The Origins of Terrorism

advertisement