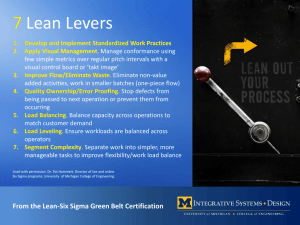

improving service productivity

advertisement