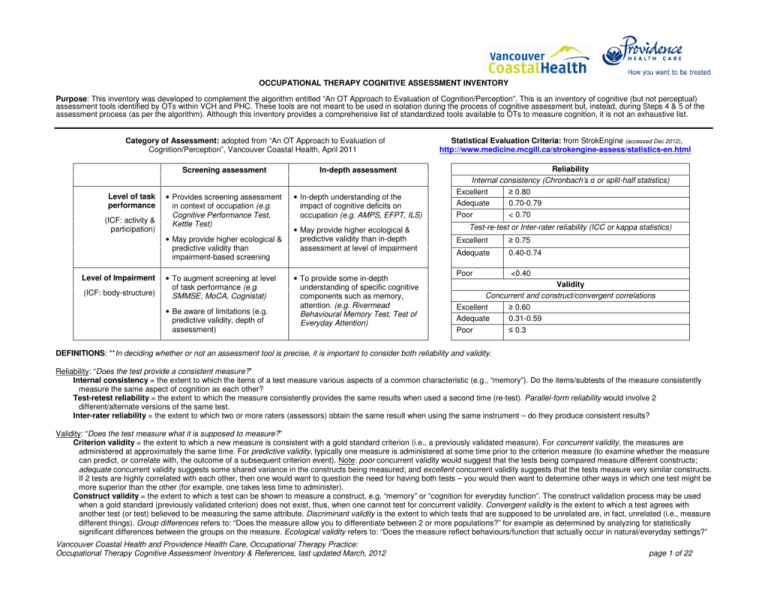

Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment In

advertisement