Patellar Tendon Ruptures

advertisement

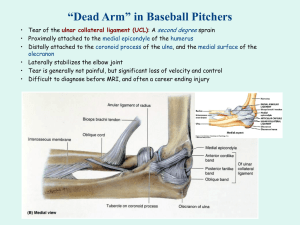

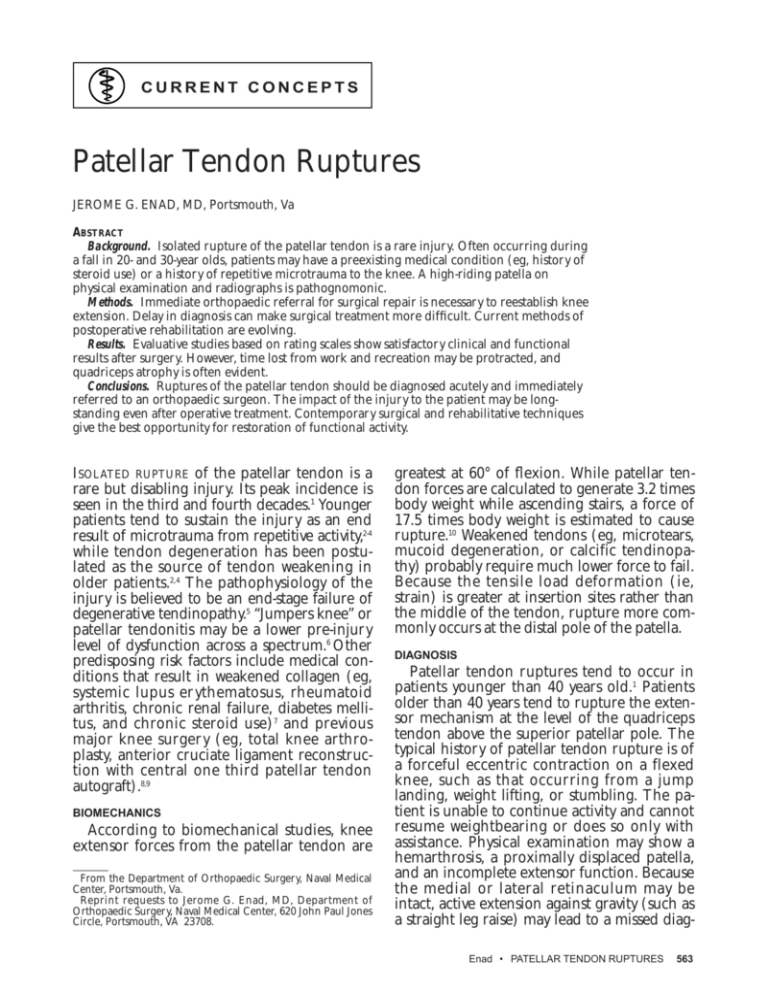

CURRENT CONCEPTS Patellar Tendon Ruptures JEROME G. ENAD, MD, Portsmouth, Va ABSTRACT Background. Isolated rupture of the patellar tendon is a rare injury. Often occurring during a fall in 20- and 30-year olds, patients may have a preexisting medical condition (eg, history of steroid use) or a history of repetitive microtrauma to the knee. A high-riding patella on physical examination and radiographs is pathognomonic. Methods. Immediate orthopaedic referral for surgical repair is necessary to reestablish knee extension. Delay in diagnosis can make surgical treatment more difficult. Current methods of postoperative rehabilitation are evolving. Results. Evaluative studies based on rating scales show satisfactory clinical and functional results after surgery. However, time lost from work and recreation may be protracted, and quadriceps atrophy is often evident. Conclusions. Ruptures of the patellar tendon should be diagnosed acutely and immediately referred to an orthopaedic surgeon. The impact of the injury to the patient may be longstanding even after operative treatment. Contemporary surgical and rehabilitative techniques give the best opportunity for restoration of functional activity. ISOLATED RUPTURE of the patellar tendon is a rare but disabling injury. Its peak incidence is seen in the third and fourth decades.1 Younger patients tend to sustain the injury as an end result of microtrauma from repetitive activity,2-4 while tendon degeneration has been postulated as the source of tendon weakening in older patients.2,4 The pathophysiology of the injury is believed to be an end-stage failure of degenerative tendinopathy.5 “Jumpers knee” or patellar tendonitis may be a lower pre-injury level of dysfunction across a spectrum.6 Other predisposing risk factors include medical conditions that result in weakened collagen (eg, systemic lupus er ythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus, and chronic steroid use)7 and previous major knee surgery (eg, total knee arthroplasty, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with central one third patellar tendon autograft).8,9 BIOMECHANICS According to biomechanical studies, knee extensor forces from the patellar tendon are From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, Va. Reprint requests to Jerome G. Enad, MD, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Naval Medical Center, 620 John Paul Jones Circle, Portsmouth, VA 23708. greatest at 60° of flexion. While patellar tendon forces are calculated to generate 3.2 times body weight while ascending stairs, a force of 17.5 times body weight is estimated to cause rupture.10 Weakened tendons (eg, microtears, mucoid degeneration, or calcific tendinopathy) probably require much lower force to fail. Because the tensile load deformation (ie, strain) is greater at insertion sites rather than the middle of the tendon, rupture more commonly occurs at the distal pole of the patella. DIAGNOSIS Patellar tendon ruptures tend to occur in patients younger than 40 years old.1 Patients older than 40 years tend to rupture the extensor mechanism at the level of the quadriceps tendon above the superior patellar pole. The typical history of patellar tendon rupture is of a forceful eccentric contraction on a flexed knee, such as that occurring from a jump landing, weight lifting, or stumbling. The patient is unable to continue activity and cannot resume weightbearing or does so only with assistance. Physical examination may show a hemarthrosis, a proximally displaced patella, and an incomplete extensor function. Because the medial or lateral retinaculum may be intact, active extension against gravity (such as a straight leg raise) may lead to a missed diagEnad • PATELLAR TENDON RUPTURES 563 A B (A) Lateral radiograph of knee with patellar tendon rupture. Notice high-riding location of patella. (B) Lateral radiograph of contralateral knee with normal patella position. nosis. However, maintenance of knee extension against a greater force is profoundly weakened and accentuates pain and deformity. In rare cases of delayed diagnosis, the patient walks with an altered gait pattern, flinging the affected leg forward in swing and showing knee instability in stance. The patient will also have difficulty rising from a chair or stair climbing. CLASSIFICATION Various classification schemes have been used to describe patellar tendon ruptures. In 1981, Siweck and Rao1 published the first large series on primary repairs of patellar tendon ruptures and arbitrarily divided injuries into immediate (diagnosis and repair occurring <2 weeks from time of injury) and chronic (diagnosis and repair occurring >2 weeks from time of injury). In 1984, Kelly et al5 classified injuries as transverse, Z-type, or inverted-U, based on the configuration of the tear at the time of surgery. In 1994, Hsu et al11 described the injuries based on the level of tendon rupture (ie, distal patellar pole, tendon midsubstance, or tibial tubercle). To date, the classification scheme based on chronicity of diagnosis and treatment has proven to be the most useful for determining prognosis and results after surgery.12 564 June 1999 • SOUTHERN MEDICAL JOURNAL • Vol. 92, No. 6 RADIOGRAPHIC STUDIES Plain radiographs of the knee in the anterior-posterior and lateral planes are helpful in confirming the diagnosis. A comparison radiograph of the contralateral knee in the lateral plane is used by the orthopaedist to quantify the amount of injury and for intraoperative planning. On the lateral views, a distinctive high-riding patella, or patella alta, compared with the contralateral knee is seen (Figure). The entire patella is located superior to the level of the intercondylar notch. The InsallSalvati ratio (length from the tibial tubercle to the inferior patellar pole divided by the length of patella) is much greater than 1.2 (ratio >1.2 defined as patella alta).13 An avulsed bone fragment attached to the tendon may be seen. High-resolution ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging are other modalities that orthopaedists have used in questionable or delayed diagnoses but are unnecessary in obvious, acute cases. TREATMENT Surgical repair is necessary to reestablish optimal extensor function in athletes and nonathletes. Nonoperative treatment is ineffective and has few indications. Immediate repair within 2 to 6 weeks of the injury has been shown to produce superior results.1,5,11 In delayed diagnoses more than 6 weeks, quadriceps contracture and fibrous adhesions make the surgical repair and restoration of patellar tendon length more complicated.1,14 The typical repair is approached anteriorly through the knee joint. The rupture tendon ends are isolated and the edges debrided. Thick, nonabsorbable sutures are woven through the tendon and an end-to-end repair or reattachment to the patella is done. Patellar height is reapproximated to that of contralateral knee. Delayed cases can be more difficult and may require preoperative traction on the patella to restore length.1,14 Restoration of patellofemoral alignment influences knee biomechanics and patellofemoral tracking. While functional results can vary, better results are often seen when the Insall ratio reapproximates that of the contralateral knee.4,15,16 Restoration of patellar tendon length optimizes knee extensor function and may diminish later patellofemoral symptoms.4,15 Subtle differences in surgical techniques have been reported in the literature, though direct comparisons between methods have not yet been examined due to the rarity of the injury. Some surgeons have used wire cerclages to reinforce repairs.1,3,5,11,14 Others have used hamstring tendons to replace or augment the patellar tendon.14,15 Synthetic materials have also been used to reinforce the repair.2,5,16-18 No reports to date have directly compared results between any of these surgical techniques. POSTOPERATIVE REHABILITATION It was generally accepted that the knee should be immobilized in extension postoperatively for the tendon to heal without tension on the repair. Therefore, 6 weeks of immobilization in a cylinder cast was done routinely by many surgeons with generally good results. 1,2,11,16 However, some authors have reported acceptable results using early rangeof-motion exercises without strict immobilization in a cast.4,15,17 Levy et al17 and Lindy et al4 noted that adequate reinforcement of the repair with a strong cerclage obviated the need for postoperative immobilization. Currently, no study has directly compared immobilization with early motion after the same surgical technique. However, with current knowledge in tendon healing and nutrition supporting the initiation of gentle, controlled movement early after the repair, more sur- geons are starting passive knee motion immediately after surgery. RESULTS Siweck and Rao1 published the first large series on primary repairs of quadriceps and patellar tendon ruptures in 1981, grading results based on range of motion and quadriceps strength. Using this scale, various authors have achieved 70% to 96% good and excellent results for primary repairs.1,11,16 Later, Kelly et al5 developed a more comprehensive evaluative scale, assessing clinical results based on physical examination, functional results based on pain and activity level, and strength using Cybex testing. Eight of 10 patients in their study achieved good or excellent functional and clinical results, but 5 of 9 patients exhibited fair or poor strength. Kuechle and Stuart2 reported on six elite athletes who had repair, and all patients achieved good or excellent functional, clinical, and strength results. Other authors on patellar tendon repairs have reported results based on criteria of Siweck and Rao,1,11,16 criteria of Kelly et al,2,5 knee scores established for other knee conditions,15,18 or clinical findings alone.4,14,17 Few studies have reported on return to activities after repair. Kelly et al5 reported on nine patients returning to their previous level of activity in 5 to 8 months, noting that the more active competitors (ie, professional athletes) returned sooner. Kuechle and Stuart2 reported that five athletic patients returned to their previous levels of function at an average of 18 months, though return to some level of athletic activities was sooner. Again, pre-injury level of athleticism appeared to play a role. More frequent unsatisfactory results have also been noted in older patients due to decreased strength and problems in regaining motion and stability.16 Further, in repairs done ≥2 weeks after injury, quadriceps atrophy and more unsatisfactory results are reported.1,14 Author’s Experience In a recent review over a 3-year period at a tertiary care military medical facility, I found that 21 active duty patients (aged 22 to 40 years; mean, 32 years) had patellar tendon repair. No patient had any medical risk factor for a patellar tendon rupture. All but one sustained the injury while playing basketball. Ten patients reported a history of pre-injury inferior knee pain. All had primary repair with a nonabsorbable synthetic cerclage. Eight paEnad • PATELLAR TENDON RUPTURES 565 tients were immobilized in knee extension, with a cast or brace for 6 weeks with weightbearing as tolerated before initiating strength and motion exercises. Thirteen patients were started on passive range-of-motion therapy immediately after surgery, with weightbearing as tolerated. Quadriceps strengthening was started at 6 weeks postoperatively. At an average follow-up of 17 months, clinical results based on Kelly et al5 classified 8 cases as excellent, 6 good, 5 fair, and 2 poor. Functional results based on Kelly et al5 classified 4 cases as excellent, 7 good, 5 fair, and 5 poor. Although not statistically significant, quadriceps atrophy and lack of full extension tended to associate with poorer clinical and functional results. With the numbers available, no significant difference was detected in clinical and functional results between the early and delayed-motion treatment groups. CONCLUSIONS Patellar tendon ruptures can have a significant effect on the athletic and nonathletic patient. The diagnosis can be made acutely with a careful history and physical examination. Predisposing medical conditions and activity level may present as risk factors. Upon diagnosis, immediate orthopaedic referral is necessary to avoid costly delays in definitive surgical repair. The impact of the injury to the patient may be long-standing, even after operative treatment. Contemporary surgical and rehabilitative techniques give the best opportunity for restoration of functional activity. 566 June 1999 • SOUTHERN MEDICAL JOURNAL • Vol. 92, No. 6 References 1. Siweck CW, Rao JP: Ruptures of the extensor mechanism of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg 1981; 63:932-937 2. Kuechle DK, Stuart MJ: Isolated rupture of the patellar tendon in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1994; 22:692-695 3. Rudig L, Ahlers J, Lengsfeld M, et al: Behandlung und Ergebnisse nach Rupturen des Ligamentum patellae. Unfallchirurg 1993; 19:214-220 4. Lindy PB, Boynton MD, Fadale PD: Repair of patellar tendon disruptions without hardware. J Orthop Trauma 1995; 9:238-243 5. Kelly DW, Carter VS, Jobe FW, et al: Patellar and quadriceps tendon ruptures—jumper’s knee. Am J Sports Med 1984; 12:375-380 6. Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW, et al: Jumper’s knee. Orthop Clin North Am 1973; 4:665-678 7. Webb LX, Toby EB: Bilateral rupture of the patellar tendon in an otherwise healthy male patient following minor trauma. J Trauma 1986; 26:1045-1048 8. Emerson RH Jr, Head WC, Malinin TI: Reconstruction of patellar tendon rupture after total knee arthroplasty with an extensor mechanism allograft. Clin Orthop 1990; 260:154-161 9. Bonamo JJ, Krinick RM, Sporn AA: Rupture of the patellar ligament after use of its central third for anterior cruciate reconstruction: a report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66:12941297 10. Zernicke RF, Garhammer J, Jobe FW: Human patellar-tendon rupture: a kinetic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg 1977; 59:179-183 11. Hsu KY, Wang KC, Ho WP, et al: Traumatic patellar tendon ruptures: a follow-up study of primary repair and a neutralization wire. J Trauma 1994; 36:658-660 12. Matava MJ: Patellar tendon ruptures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1996; 4:287-296 13. Insall J, Salvati E: Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology 1971; 101:101-104 14. Ecker ML, Lotke PA, Glazer RM: Later reconstruction of the patellar tendon. J Bone Joint Surg 1979; 61:884-886 15. Larson RV, Simonian PT: Semitendinosus augmentation of acute patellar tendon repair with immediate mobilization. Am J Sports Med 1995; 23:82-86 16. Larsen E, Lund PM: Ruptures of the extensor mechanism of the knee joint. Clin Orthop 1986; 213:150-153 17. Levy M, Goldstein J, Rosner M: A method of repair for quadriceps tendon or patellar ligament (tendon) ruptures without cast immobilization. Clin Orthop 1987; 218:297-301 18. Miskew DBW, Pearson RL, Pankovich AM: Mersilene strip suture in repair of disruptions of the quadriceps and patellar tendon. J Trauma 1980; 20:867-872