Promising practices supporting low-income, first

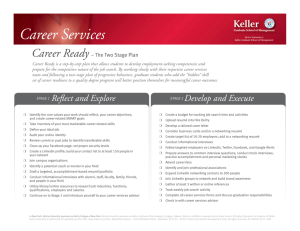

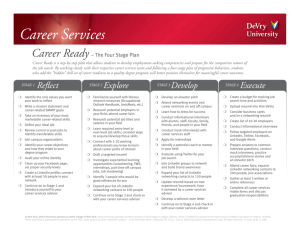

advertisement