Assumptions in. Measuring Advertising Effectiveness

advertisement

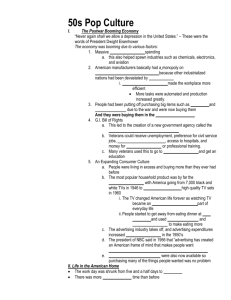

Assumptions in. Measuring Advertising Effectiveness THOMAS T. SEMON Thomas E. CofFin's article, " A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising EfFectiveness," published in the July, 1963, issue outlined a logical model and a practical research approach, and indicated further improvements to be made. However, the author of the present article believes that certain basic assumptions need further study. Journal of Marketing, Vol. 28 (July, 1964), pp. 43-44. PIONEERING Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness" by Dr. Thomas E. Coffin was an outstanding contribution to marketing literature.^ But it did not point up the possible dangers in the tacit acceptance of two of his basic assumptions. Exposure Equivalent Readers and viewers were defined as "those who claimed to have read one or more of the last four weekly issues (of Magazine A) or watched one or more of the last four broadcasts.''^ The definition is clear; and the use of the advertising vehicle, rather than the advertisement itself as the exposure criterion is sound. But is the assumption correct—^that exposure to one or more of the last four showings of TV programs is equivalent to one or more instances of reading in one or more of the last four issues of a weekly magazine? Although this equivalence is not explicitly stated in the article, it is implicit, in that the analyses presented would be pointless without this assumption of equivalence. The assumption of equivalence is not necessarily wrong, but it has not been proved. If the analysis presented by Coffin is to serve as a model for practical application, equivalence should be established on a cost basis. Advertising Analogs The study comprised two carefully planned waves of interviews with the same persons, three months apart. The reported media exposure and buying levels were compared between the two waves for each person, and the person classified accordingly. For instance, a person who reported exposure to TV in the second wave, but not in the first, was classified as having "started television.''^ Coffin draws a close parallel between such exposure-defined groups and possible advertising strategies. Although the analogies are plausible, their accuracy is doubtful in terms of the exposure definition. This definition implies a process whose occurrence or nonoccurrence within a 4-week period constitutes a significant dichotomy. The results reported fail to bear out this implication. If the occurrence or nonoccurrence of exposure were a significant diThomas E. Coffin, "A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising Effectiveness," JOURNAL OF MARKETING. Vol. 27 (July, 1963), pp. 1-10. Same reference as footnote 1, at p. 3. Same reference as footnote 1, at p. 5. 43 44 Journal of Marketing, July, 1964 CHANGES I N BUYING LEVEL RELATED TO CHANGES IN EXPOSURE Exposure change Increased exposure units (combined) "Started" viewing "Started" reading Average "started"" Decreased exposure units (combined) "Stopped" viewing "Stopped" reading Average "stopped"" Buying Levels Wave I Wave II Change 19.6% 21.0% 18.7 20.5 19.6 20.6 21.0 20.8 21.0 19.4 21.6 19.9 20.7 19.2 19.4 19.3 + + + + 1.4% 1.9 .5 1.2 - 1.6 - 2.4 - .5 - 1.4 " These averages, computed by the author, assume that equal numbers of persons "started" (or "stopped") reading and viewing. The averages are probably within ± .3 of the figures shown. chotomy, it should be associated with differences in buying levels that are clearly greater than buyinglevel changes attributed to unspecified, general change in degree of exposure. Changes in buying levels were shown according to two exposure change criteria. In Table 2 of the Coffin article the criterion was increase or decrease in exposure units, regardless of medium.* In Table 4, buying levels were analyzed according to reported "starting, maintaining, or stopping" of exposure in the two media separately.^ The accompanying table combines data from these sources. It is obvious that "starting" or "stopping" to read or view is not associated with changes in buying level that are substantially greater than those noted in connection with general, unspecified changes in the overall level of exposure. Conclusions Two tentative, related conclusions can be drawn. 1. Either exposure turnover is less important than has been assumed, or the criterion of reported exposure within the last four weeks is not the most relevant and discriminating criterion available. 2. By leaving out the alternatives of increasing or decreasing advertising weight, the strategies of "advertising analogs" did not include strategies as important as and more realistic than those presented in the Coffin article. Same reference as footnote 1, at p. 5. • ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Thomas T. Semon is an rndependent research consultant. He was formerly a research executive on the staff of Stewart, Dougall, and Associates, Inc., and then of Marplan. Mr. Semon is the author of many articles and pamphlets on various aspects of research in marketing. Same reference as footnote 1, at p. 4. •MARKETING MEMOBrand Loyalty Is a Sometime Thing . . . Marketing men are often heard to refer to "a hard core franchise of loyal users" for their brands. This delusion is generally fostered by a relatively flat, only moderately changing brand share pattern. The marketing vice president pictures in his mind's eye a solid foundation of happy users contentedly buying his product month after month. In addition to these "loyal" users, he pictures a small group of "switchers" who come and go according to advertising and promotion influences of the moment. Though he may not say so, he considers these "switchers" as really not quite respectable—like camp followers ready to desert when a new and better offer arises. But certainly, he figures, they are a "minority" of his loyal dedicated franchise. In actuality, his franchise may present a much less reassuring spectacle. His business—especially in frequently purchased, small ticket food items—may well be made up of a flock of fickle, sharp-eyed, mercenary buyers, ready and anxious to be lured away by a more attractive brand ofiFer. Every trip to the store presents an opportunity for a new affair with a new brand. Indeed, the term "brand lethargy" is probably more apropos than "brand loyalty." While less satisfying, perhaps it would serve as a constant reminder that you hold your customers only temporarily and by default on the part of a more aggressive suitor. Your customer is ready and willing to leave your fold at a moment's notice. —John J. Houlahan, "The Delusion of 'Loyal' Users," Food Business, Vol. 11 (October, 1963), p. 28.