Broadcasting bad health - Center for Science in the Public Interest

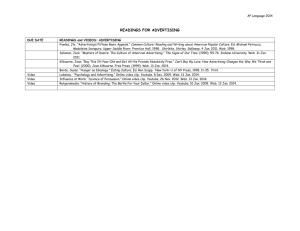

advertisement