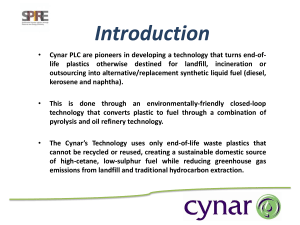

Fossil Fuel Subsidy and Pricing Policies

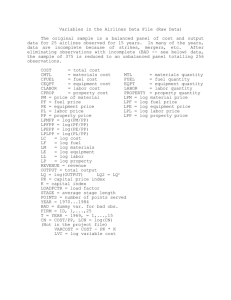

advertisement