RADIO AND TELEVISION INTERVIEWS A good press release could

advertisement

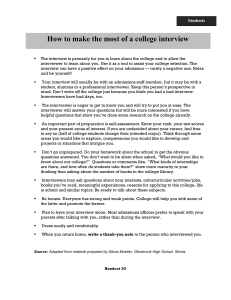

RADIO AND TELEVISION INTERVIEWS A good press release could result in an invitation to appear on a radio or TV programme. When you receive such an invitation, there are certain key pieces of information you need before you can make the decision whether or not you should accept that invitation. Use this checklist to get that information when the station first contacts you. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Who is the audience? What is the topic? What areas to be covered? What is the angle? Why am I being asked to speak? What is my interview sandwiched between? Who else will be on the show? What time will it go out? What time will it be recorded at, if it’s not live? How long will the broadcast last? (Or: How long will the recording last?) Is it a panel or a one-to-one? Who will be on the panel? What position will they take on the topic? Is it a phone in interview? Where will the interview take place? How much preparation time is available before the broadcast? How can I get there? What are the parking/security arrangements? If you decide that you can reach a specific audience through the programme, you agree to go on, but only if you have enough time to prepare. Never accept an invitation to ‘go on air three minutes from now’ by phone. You would never choose to address 500 people in a hall without preparing what to say; why should you address 500,000 people through their radios without preparation? HOW TO PREPARE FOR A RADIO OR TV INTERVIEW Who is my audience? Decide whom you’re talking to. Is it housewives, footballers, possible sponsors for a new project, or customers for your business. You can’t decide exactly what you’re going to say until you have decided exactly who your audience is. Your target audience will usually be a subsection of the total audience for the programme. You can guess who the audience, for the programme, is from the time it is broadcast. For example, Morning Ireland is usually on at 7.30am to 9am – the audience is business people going to work. What is the audience’s present position on the topic? Try to put yourself in the shoes of a member of your target audience. Guess exactly what they think about your topic. If you cannot do this, chat to a few members of your target audience and work out what they are thinking about the issues you’re going to address. Here’s what you need to write down: WHERE THE AUDIENCE IS NOW What they know VS What they feel What do I want my target audience to be thinking, saying or doing after the interview? You must have a communication goal. This goal is to shift the target audience from position A to position B. Identifying your audience and your communication goal are the two most important steps in preparing for a radio interview. If you get these wrong your interview will not be effective. Here’s what you write down: WHERE I WANT THE AUDIENCE TO BE AFTER MY INTERVIEW What they’ll know VS What they’ll feel Don’t be over-ambitious. In a four-minute interview, for example, if you’re a very good talker, you might make your chosen audience remember 3 pieces of information. You certainly won’t make them remember 6 pieces of information. When you have worked out the 3 pieces of information you want them to remember, and the emotional decision or opinion you want them to adopt, write them in the first column of the preparation grid. (see below) PREPARING FOR AN INTERVIEW GRID What must the audience remember? Those points – interesting and memorable Obvious questions Nasty questions The second column of the grid is headed ‘Making the Points Memorable’. In this column, list examples with specific, graphic details which vividly illustrate the points you wish to make. For each point you may wish to choose one or two vivid examples. Let’s imagine that the first point you want them to remember is that the new road will cut traffic jams. To make that memorable, you need to illustrate it, put details into it, and make listeners draw their own pictures. Like this: “Up until now. If you wanted to get to Bigtown from Littletown, it could take you an hour in the afternoon, but two hours at busy times. Factories in Bigtown had huge problems with workers arriving late through no fault of their own.” “Anyone who had to do the journey regularly knows that they could be sitting at the third bend, where the fire station is, for three quarters of an hour or more, inching forward every ten minutes”. “Parents found they had to get small children up at 7 in order to get them to their playgroup at 9. That’s going to change”. In the second column you write the examples, pictures, stories, supportive evidence that will make each point interesting, understandable and memorable. In the third column, you list the obvious questions. (A quick brainstorm with colleagues will give you the contents of the two last columns.) In the fourth column, you list the questions you sincerely hope you will not be asked. The stinkers! Now, take a pen, close your eyes and aim at one of the two columns on the right. Read aloud the question on which your pen lands, and answer it, seeking to link to one of the points you want to make. With a little practise, it becomes easy to get to the items you have prepared to offer. It’s important to remember that offering is precisely what you are doing. You are not setting out to avoid questions or manipulate the interviewer. You are simply moving the interview from being an oral exam into being an opportunity for you to offer interesting added value information to the listeners. Talk your answers out aloud. Sometimes, we hear ourselves saying something we realise does not do justice to the point we wish to make. It’s a lot better to find that out at home, before we go to the studio, than live, on the air. When you’re sure of what you’re going to offer, take a card and, with a big, black felt-tip pen, put down a few trigger words: • • • All of the family will enjoy our event Protecting our biodiversity protects all of us Everyone should take part in National Heritage Week Make sure you also note down any figures, names or other factual data, which might elude you, under pressure. 10 MEDIA INTERVIEW DON’TS • • • • • • • • • • Don’t bring the preparation grid into the studio: it’s too complicated. Bring the card. You may not need it but it is a reassurance. Don’t write out full sentences on the card: radio presenters dread the interviewee who comes and reads aloud, rather than answering questions in a vivid immediate way Don’t say ‘I’m glad you asked me that question’ or ‘that’s a good question’. Just get to your answer. Don’t tell the interviewer what to ask you. Stay on your own side of the fence and offer what you came to offer. Don’t argue with the interviewer. It’s not him or her you have to persuade. It’s the people at home. Think of the interviewer as a telephone you’re using to get to that wider public. Nobody fights with a telephone. Don’t attack the man or woman, attack the issue. No personal insults or characterisations. Don’t repeat the words of an accusation. If an interviewer says ‘I put it to you that your organisation has been associated with murder, rape and pillage’, then responding ‘My organisation has never been associated with murder, rape and pillage’ ensures that the people listening will certainly make the link between murder, rape, pillage and your organisation. By repeating it, you’ve drummed it into their minds. Instead, get to the positive. Don’t put padding in front of your answers: ‘Well, it’s important that your listeners see this issue in its wider context.’ Cut to the chase. Get to the point. Don’t bring a mobile phone, a pen with a clicky end, a pager or a watch that tweets on the hour into a TV/Radio studio. Don’t wait for the right question. It may never arrive. Find a way to make your point without it. COPING WITH NERVES You have prepared the points you want to make, your plan for handling obvious questions and your method of coping with nasty questions. In theory, you’re sitting pretty. In reality, it’s at this point that nervousness sets in. Most good performers suffer nerves before they go onstage or in front of a microphone. It is an appropriate response before a challenging public appearance, especially if the public appearance is important to people other than oneself. Adrenalin begins to pump through the body in preparation for the perceived challenge. Adrenalin is the hormone that prepared prehistoric men and women for fight or flight. It gets the body ready for action. Adrenalin has side effects. It gives a dry mouth. It can make hands shake. Make sure, any time you are broadcasting, that you have water within reach, and use it. If you know your hands tend to tremble when you are nervous, clench them very tightly and hold them clenched, before you go on the air, until they hurt. Then relax. Your hands will find it quite difficult to tremble for some time afterwards. The key to controlling nervousness during the interview is to stop looking at yourself. Keep your attention on the audience. Focus on moving the audience from position A to position B. Your performance will only deteriorate if you let your attention become divided between the interview situation on the one hand and conducting an internal dialogue about performance on the other. A FEW EXTRA FACTORS TO KEEP IN MIND WHEN PREPARING The first and last questions follow a pattern. In most interviews, the first question is what’s the story here? In most interviews, the last question is where do we go from here? Different words are used but the meaning is usually some variant of these two questions. Prepare accordingly. Keep control of the interview by talking about specific examples. If you talk in general terms, you’re easy to interrupt and difficult to remember. Use detailed examples to illustrate your points. You’re the expert on your topic. Set out to be interesting. Don’t force the interviewer to ask a million questions to get the story out of you. If you don’t know the answer, say so. If you don’t know the answer to a question, you can either say you don’t know or prove you don’t know. Never prove you don’t know. Say it and offer to solve the information problem as soon as you can. If you are confused by the question get it clarified. Use first names rarely Don’t try to flatter interviewers by using their first name. Once at the beginning – only. Your target audience is out there in kitchens and motorcars. If you continually use the interviewer’s name, it makes the audience feel they’re eavesdropping – they’re outsiders. Go live if possible If you have an option live broadcasting is best as you can control what is said and it’s not going to be edited. People tend to perform better live, despite (or perhaps because of) the possibility of making an error. The main problem with taped material is that others can edit your input. They mean you no harm, but their priorities are not your priorities.