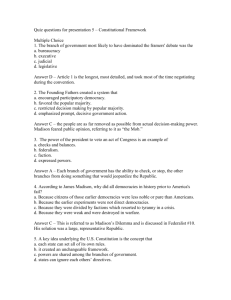

The Founding Fathers: A Reform Caucus in Action - Jb-hdnp

advertisement

ENSURE THAT YOU TAKE THE QUIZ LINKED AT THE END OF THE READING

10

Constitutional Government

Framing the Constitution:

Elitist or Democratic Process?

A remarkable fact about the United States government is that it has operated for two hundred years on the basis of a written Constitution. Does this suggest unusual sagacity on

the part of the Founding Fathers, or exceptional luck? What was involved in framing the

Constitution?

In the following selection John P. Roche suggests that the framing of the Constitution

was essentially a democratic process involving the reconciliation of a variety of state, political, and economic interests. Roche writes that "the Philadelphia Convention was not a

College of Cardinals or a council of Platonic guardians working in a manipulative, predemocratic framework; it was a nationalist reform caucus that had to operate with great delicacy and skill in a political cosmos full of enemies to achieve one definitive goal—

popular approbation." Roche recognizes that the framers, collectively, were an elite, but

he is careful to point out that they were a political elite dedicated for the most part to establishing an effective and at the same time controlled national government that would be

able to overcome the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. The framers were not,

says Roche, a cohesive elite dedicated to a particular set of political or economic assumptions beyond the simple need to create a national government that would be capable of

reconciling disparate state interests. The Constitution was "a vivid demonstration of effective democratic political action, and of the forging of a national elite which literally persuaded its countrymen to hoist themselves by their own bootstraps."

2

The Founding Fathers:

A Reform Caucus in Action

John P. Roche

O v e r the last century and a half, the work of the C o n s t i t u t i o n a l C o n v e n t i o n and

the motives of the Founding Fathers have been analyzed under a number of different ideological auspices. T o one generation of historians, the hand of G o d was

m o v i n g i n the assembly; under a later dispensation, a dialectic (at various levels of

philosophical sophistication) replaced the Deity: "relationships of production"

John P. Roche

11

moved i n t o the niche pteviously reserved for Love o f C o u n t r y . Thus i n counterpart

to the Zeitgeist, the ftamers have undergone miraculous metamorphoses: at one time

acclaimed as liberals and bold social engineers, today they appear i n the guise o f

sound Burkean conservatives, m e n w h o i n our time would subscribe to Fortune,

look to W a l t e r L i p p m a n n for p o l i t i c a l theory, and chuckle patronizingly at the antics of Barry Goldwater. T h e i m p l i c i t assumption is that i f James Madison were

among us, he would be President of the Ford Foundation, while Alexander H a m i l t o n would chair the C o m m i t t e e for Economic Development.

T h e "Fathers" have thus been admitted t o our best circles; the revolutionary

ferocity w h i c h confiscated a l l T o r y property i n reach and populated N e w

Brunswick w i t h outlaws has been converted by the " M i l t o w n S c h o o l " o f A m e r i c a n

historians i n t o a benign dedication t o "consensus" a n d "prescriptive rights." T h e

Daughters of the A m e r i c a n R e v o l u t i o n have, t h r o u g h the ministrations o f Professors Boorstin, Hartz, and Rossiter, at last found ancestors w o r t h y o f their descendants. I t is n o t my purpose here to argue that the "Fathers" were, i n fact, radical

revolutionaries; that proposition has been b r i l l i a n t l y demonstrated by Robert R.

Palmer i n his Age of the Democratic Revolution. M y concern is w i t h the future posit i o n that n o t o n l y were they revolutionaries, but also they were democrats. Indeed,

i n my view, there is one fundamental t r u t h about t h e Founding Fathers that every

generation o f zeitgeisters has done its best to obscure: they were first and foremost

superb democratic politicians. I suspect t h a t i n a contemporary setting, James

Madison would be Speaker o f the House o f Representatives and H a m i l t o n would

be the eminence grise d o m i n a t i n g {pace Theodore Sorensen or Sherman Adams) t h e

Executive Office of the President. T h e y were, w i t h their colleagues, political men—

not metaphysicians, disembodied conservatives or Agents o f H i s t o r y — a n d as recent research i n t o the nature o f A m e r i c a n politics i n the 1780s confirms, they were

committed (perhaps w i l l y - n i l l y ) to w o r k i n g w i t h i n the democratic framework,

w i t h i n a universe o f public approval. Charles Beard and the filiopietists t o the contrary n o t w i t h s t a n d i n g , the Philadelphia C o n v e n t i o n was n o t a College o f Cardinals or a c o u n c i l of Platonic guardians w o r k i n g w i t h i n a manipulative, predemocratic framework; i t was a nationalist reform caucus w h i c h had to operate w i t h great

delicacy and skill i n a p o l i t i c a l cosmos full o f enemies to achieve the one d e f i n i t i v e

goal—popular approbation.

Perhaps the time has come, to borrow W a l t o n Hamilton's fine phrase, t o raise

the framers from immortality to mortality, to give t h e m credit for their magnificent

demonstration o f the art of democratic politics. T h e p o i n t must be reemphasized:

they made history and d i d i t w i t h i n the limits o f consensus. There was n o t h i n g i n evitable about the future i n 1787; the Zeitgeist, that fine Hegelian technique o f begging causal questions, could only be discerned i n retrospect. W h a t they d i d was t o

hammer out a pragmatic compromise w h i c h would b o t h bolster the " n a t i o n a l interest" and be acceptable to the people. W h a t inspiration they got came from their

collective experience as professional politicians i n a democratic society. A s John

Dickinson put i t to his fellow delegates o n August 13, "Experience must be our

guide. Reason may mislead us."

I n this context, let us examine the problems they confronted and the solutions

they evolved. T h e C o n v e n t i o n has been described picturesquely as a counterrevolutionary junta and the C o n s t i t u t i o n as a coup d'etat, b u t this has been

12

Constitutional Government

accomplished by w i t h d r a w i n g the whole history of the movement for constitutional

reform from its true context. N o doubt the goals of the constitutional elite were

"subversive" to the existing p o l i t i c a l order, but i t is overlooked that their subversion

could only have succeeded i f the people of the U n i t e d States endorsed i t by regularized procedures. Indubitably they were " p l o t t i n g " to establish a m u c h stronger central government t h a n existed under the Articles, but only i n the sense i n w h i c h one

could argue equally w e l l that John F. Kennedy was, from 1956 to 1960, " p l o t t i n g " to

become President. I n short, o n the fundamental procedural level, the C o n s t i t u t i o n alists had to work according to the prevailing rules of the game. W h e t h e r they liked

it or n o t is a topic for spiritualists—and is irrelevant: one may be quite certain that

had W a s h i n g t o n agreed to play the de Gaulle (as the C i n c i n n a t i once urged),

H a m i l t o n w o u l d w i l l i n g l y have held his horse, but such fertile speculation i n no

way alters the actual context i n w h i c h events took place.

I

W h e n the Constitutionalists went f o r t h to subvert the Confederation, they utilized

the mechanisms of p o l i t i c a l legitimacy. A n d the roadblocks w h i c h confronted them

were formidable. A t the same t i m e , they were endowed w i t h certain potent p o l i t i cal assets. T h e history of the U n i t e d States from 1786 to 1790 was largely one of a

masterful employment of p o l i t i c a l expertise by the Constitutionalists as against

bumbling, erratic behavior by the opponents of reform. Effectively, the Constitutionalists had to induce the states, by democratic techniques of coercion, to emasculate themselves. T o be specific, i f N e w York had refused to j o i n the new U n i o n ,

the project was doomed; yet before N e w York was safely i n , the reluctant state legislature had suasponte to take the following steps: (1) agree to send delegates to the

Philadelphia C o n v e n t i o n ; (2) provide maintenance for these delegates (these were

distinct stages: N e w Hampshire was early i n naming delegates, but d i d n o t provide

for their maintenance u n t i l July); (3) set up the special ad hoc c o n v e n t i o n to decide o n ratification; and (4) concede to the decision of the ad hoc c o n v e n t i o n that

N e w York should participate. N e w York admittedly was a tricky state, w i t h a strong

interest i n a status quo w h i c h permitted her to exploit N e w Jersey and Connecticut,

but the same legal hurdles existed i n every state. A n d at the risk of becoming boring, i t must be reiterated that the only weapon i n the Constitutionalist arsenal was

an effective mobilization of public o p i n i o n .

T h e group w h i c h undertook this struggle was an interesting amalgam of a few

dedicated nationalists w i t h the self-interested spokesmen of various parochial bailiwicks. T h e Georgians, for example, wanted a strong central authority to provide

military p r o t e c t i o n for their huge, underpopulated state against the Creek Confederacy; Jerseymen and Connecticuters wanted to escape from economic bondage to

N e w York; the Virginians hoped to establish a system w h i c h w o u l d give that great

state its rightful place i n the councils of the republic. T h e d o m i n a n t figures i n the

politics of these states therefore cooperated i n the call for the C o n v e n t i o n . I n other

states, the thrust towards n a t i o n a l reform was taken up by opposition groups who

added the " n a t i o n a l interest" to their weapons system; i n Pennsylvania, for i n -

John P. Roche

13

stance, the group fighting to revise the C o n s t i t u t i o n of 1776 came out four-square

behind the Constitutionalists, and i n N e w York, H a m i l t o n and the Schuyler

ambiance took the same tack against George C l i n t o n . There was, of course, a large

element of personality i n the affair: there is reason to suspect that Patrick Henry's

opposition to the C o n v e n t i o n and the C o n s t i t u t i o n was founded o n his c o n v i c t i o n

that Jefferson was behind b o t h , and a close study of local politics elsewhere w o u l d

surely reveal that others supported the C o n s t i t u t i o n for the simple (and politically

quite sufficient) reason that the " w r o n g " people were against i t .

T o say this is n o t to suggest that the C o n s t i t u t i o n rested o n a foundation of

impure or base motives. I t is rather to argue that i n politics there are n o immaculate conceptions, and that i n the drive for a stronger general government, motives

of all sorts played a part. Few m e n i n the history of m a n k i n d have espoused a view

of the " c o m m o n good" or "public interest" t h a t m i l i t a t e d against their private status; even Plato w i t h all his reverence for disembodied reason managed to put

philosophers o n top of the pile. T h u s i t is n o t surprising that a number of diversified private interests j o i n e d to push the nationalist public interest; what w o u l d

have been surprising was the absence of such a pragmatic united f r o n t . A n d the

fact remains that, however motivated, these m e n d i d demonstrate a willingness to

compromise their parochial interest i n behalf of an ideal w h i c h took shape before

their eyes and under their ministrations.

As Stanley Elkins and Eric M c K i t r i c k have suggested i n a perceptive essay [76

Political Science Quarterly 181 (1961)], what distinguished the leaders of the Constitutionalist caucus from their enemies was a " C o n t i n e n t a l " approach to political, economic and military issues. T o the extent that they shared an institutional base of operations, it was the Continental Congress (thirty-nine of the delegates to the Federal

Convention had served i n Congress), and this was hardly a locale w h i c h inspired respect for the state governments. Robert de Jouvenal observed French politics half a

century ago and noted that a revolutionary Deputy had more i n common w i t h a nonrevolutionary Deputy than he had w i t h a revolutionary non-Deputy; similarly one can

surmise that membetship i n the Congress under the Articles of Confederation worked

to establish a Continental frame of reference, that a Congressman from Pennsylvania

and one from South Carolina would share a universe of discourse w h i c h provided them

w i t h a conceptual common denominator vis-a-vis their respective state legislatures.

This was particularly true w i t h respect to external affairs: the average state legislator

was probably about as concerned w i t h foreign policy t h e n as he is today, but Congressmen were constantly forced to take the broad view of American prestige, were compelled to listen to the reports of Secretary John Jay and to the dispatches and pleas

from their frustrated envoys i n Britain, France, and Spain. From considerations such as

these, a " C o n t i n e n t a l " ideology developed w h i c h seems to have demanded a revision

of our domestic institutions primarily o n the ground that only by invigorating out general government could we assume our rightful place i n the international arena. Indeed,

an argument w i t h great force—particularly since Washington was its incarnation—

urged that our very survival i n the Hobbesian jungle of world politics depended upon a

reordering and strengthening of our national sovereignty.

T h e great achievement of the Constitutionalists was their ultimate success i n

convincing the elected representatives of a majority of the w h i t e male population

14

Constitutional Government

t h a t change was imperative. A small group of p o l i t i c a l leaders w i t h a C o n t i n e n t a l

vision and essentially a consciousness of the U n i t e d States' international impotence,

provided the m a t r i x of the movement. T o their standard other leaders rallied w i t h

their o w n parallel ambitions. T h e i t gteat assets were (1) the presence i n their caucus of the one authentic A m e r i c a n "father figure," George W a s h i n g t o n , whose prestige was enormous; (2) the energy and talent of their leadership ( i n w h i c h one must

include the towering intellectuals of the t i m e , John Adams and Thomas Jefferson,

despite their absence abroad), and their communications " n e t w o r k , " w h i c h was far

superior to a n y t h i n g o n the opposition side; (3) the preemptive skill w h i c h made

" t h e i r " issue T h e Issue and kept the locally oriented opposition permanently o n the

defensive; and (4) the subjective considetation that these m e n wete spokesmen of a

new and compelling credo: American nationalism, that ill-defined but nonetheless

potent sense of collective purpose that emerged from the A m e r i c a n Revolution.

Despite great i n s t i t u t i o n a l handicaps, the Constitutionalists managed i n the

mid-1780s to m o u n t an offensive w h i c h gained m o m e n t u m as yeats went by. T h e i r

greatest problem was lethargy, and paradoxically, the number of barriers i n their

path may have proved an advantage i n the long r u n . Beginning w i t h the i n i t i a l battle to get the C o n s t i t u t i o n a l C o n v e n t i o n called, the delegates appointed, they

could never relax, never let up the pressure. I n practical terms, this meant that the

local "organizations" created by the Constitutionalists were perpetually i n movem e n t b u i l d i n g up their cadres for the next fight. ( T h e w o r d organization has to be

used w i t h great caution: a p o l i t i c a l organization i n the U n i t e d States—as i n contemporary England—generally consisted of a magnate and his following, or a coalit i o n of magnates. T h i s d i d n o t necessarily mean that i t was "undemocratic" or "aristocratic," i n the A r i s t o t e l i a n sense of the word: w h i l e a few magnates such as the

Livingstons could draft their followings, most exercised t h e i t leadeiship w i t h o u t coercion o n the basis of popular endorsement. T h e absence of organized opposition

did n o t imply the impossibility of c o m p e t i t i o n any more t h a n low public participat i o n i n elections necessarily indicated an undemocratic suffrage.)

T h e Constitutionalists got the j u m p o n the "opposition" (a collective n o u n :

oppositions w o u l d be more correct) at the outset w i t h demand for a C o n v e n t i o n .

T h e i r opponents were caught i n an old p o l i t i c a l trap: they were n o t being asked to

approve any specific program of reform, but only to endorse a meeting to discuss

and recommend needed reforms. I f they took a hard line at the fitst stage, they were

put i n the position of glorifying the status quo and of denying the need for any

changes. Moreover, the Constitutionalists could go to the people w i t h a persuasive

argument for "fair p l a y " — " H o w can you condemn reform before you k n o w precisely

what is involved?" Since the state legislatures obviously w o u l d have the final say o n

any proposals that m i g h t emerge from the C o n v e n t i o n , the Constitutionalists were

merely reasonable m e n asking for a chance. Besides, since they d i d n o t make any

concrete proposals at that stage, they were i n a position to capitalize o n every sort

of generalized discontent w i t h the Confederation.

Perhaps because of their poor intelligence system, pethaps because of overconfidence generated by the failure of all previous efforts to alter the Articles, the opposition awoke too late to the dangers that confronted t h e m i n 1787. N o t only did

the Constitutionalists manage to get every state but Rhode Island (where politics

John P. Roche

15

was enlivened by a party system reminiscent of the "Blues" and the "Greens" i n the

Byzantine Empire) to appoint delegates to Philadelphia, but w h e n the results were

i n , i t appeared that they dominated the delegations. G i v e n the apathy of the opposition, this was a natural phenomenon: i n an ideologically nonpolarized p o l i t i c a l atmosphere those w h o get appointed to a special committee ate likely to be the m e n

who supported the movement for its creation. Even George C l i n t o n , w h o seems to

have been the first opposition leader to awake to the possibility of trouble, could

not prevent the N e w York legislature from appointing Alexander H a m i l t o n —

though he did have the foresight to send two of his h e n c h m e n to dominate the delegation. Incidentally, m u c h has been made of the fact t h a t the delegates to

Philadelphia were n o t elected by the people; some have adduced this fact as evidence of the "undemocratic" character of the gathering. But put i n the context of

the time, this argument is w h o l l y specious: the central government under the A r t i cles was considered a creature of the component states and i n all the states but

Rhode Island, Connecticut, and N e w Hampshire, members of the n a t i o n a l C o n gress were chosen by the state legislatures. T h i s was n o t a consequence of elitism or

fear of the mob; i t was a logical extension of states' rights doctrine to guarantee that

the national i n s t i t u t i o n d i d n o t end-run the state legislatures and make direct contact w i t h the people.

II

W i t h delegations safely named, the focus shifted to Philadelphia. W h i l e w a i t i n g for

a quorum to assemble, James Madison got busy and drafted the so-called Randolph

or V i r g i n i a Plan w i t h the aid of the V i r g i n i a delegation. T h i s was a p o l i t i c a l masterstroke. Its consequence was that once business got underway, the framework of the

discussion was established o n Madison's terms. There was n o interminable argument over agenda; instead the delegates took the V i r g i n i a Resolutions—"just for

purposes of discussion"—as their p o i n t of departure. A n d along w i t h Madison's proposals, many of w h i c h were buried i n the course of the summer, went his majot

premise: a new start o n a C o n s t i t u t i o n rather t h a n piecemeal amendment. T h i s was

not necessarily revolutionary—but Madison's proposal t h a t this " l u m p sum"

amendment go i n t o effect after approval by nine states (the A r t i c l e s required unanimous state approval for any amendment) was thoroughly subversive.

Standard treatments of the C o n v e n t i o n divide the delegates i n t o "nationalists"

and "states' righters" w i t h various improvised shadings ("moderate nationalists,"

etc.), but these are a posteriori categories w h i c h obfuscate more t h a n they clarify.

W h a t is striking to one w h o analyzes the C o n v e n t i o n as a case study i n democratic

politics is the lack of cleat-cut ideological divisions i n the C o n v e n t i o n . Indeed, I

submit that the evidence—Madison's Notes, the correspondence of the delegates,

and debates o n ratification—indicates that this was a remarkably homogeneous body

on the ideological level. Yates and Lansing, Clinton's two chaperones for H a m i l t o n ,

left i n disgust o n July 10. (Is there anything mote tedious t h a n sitting through endless disputes o n matters one deems fundamentally misconceived? I t takes an i r o n w i l l

to spend a h o t summer as an ideological agent provocateur.)

Luther M a r t i n ,

16

Constitutional Government

Maryland's bibulous narcissist, left o n September 4 i n a huff w h e n he discovered that

others did n o t share his self-esteem; others went home for personal reasons. But the

hard core of delegates accepted a grinding regimen throughout the a t t r i t i o n of a

Philadelphia summer precisely because they shared the Constitutionalist goal.

Basic differences of o p i n i o n emerged, of course, but these were n o t ideological;

they were structural. I f the so-called "states' rights" group had n o t accepted the fundamental purposes of the C o n v e n t i o n , they could simply have pulled out and by

doing so have aborted the whole enterprise. Instead of b o l t i n g , they returned day after day to argue and to compromise. A n interesting symbol of this basic homogeneity was the i n i t i a l agreement o n secrecy: these professional politicians d i d n o t want

to become prisoners of publicity; they wanted to retain that freedom of maneuver

w h i c h is only possible w h e n m e n are n o t forced to take public stands i n the preliminary stages of negotiation. There was n o legal means of b i n d i n g the tongues of the

delegates: at any stage i n the game a delegate w i t h basic principled objections to

the emerging project could have taken the stump (as Luther M a r t i n d i d after his

e x i t ) and denounced the C o n v e n t i o n to the skies. Yet Madison d i d n o t even i n f o r m Thomas Jefferson i n Paris of the course of the deliberations and available correspondence indicates that the delegates generally observed the i n j u n c t i o n . Secrecy

is certainly uncharacteristic of any assembly marked by strong ideological polarizat i o n . T h i s was noted at the t i m e : the New York Daily Advertiser, August 14, 1787,

commented that the "profound secrecy h i t h e r t o observed by the C o n v e n t i o n [we

consider] a happy omen, as i t demonstrates that the spirit of party o n any great and

essential p o i n t cannot have arisen to any h e i g h t . "

Commentators o n the C o n s t i t u t i o n w h o have read The Federalist i n lieu of

reading the actual debates have credited the Fathers w i t h the i n v e n t i o n of a sublime concept called "Federalism." U n f o r t u n a t e l y , The Federalist is probative evidence for only one proposition: that H a m i l t o n and Madison were inspired propagandists w i t h a genius for retrospective symmetry. Federalism, as the theory is

generally defined, was an improvisation w h i c h was later promoted i n t o a political

theory. Experts o n "federalism" should take to heart the advice of David H u m e ,

w h o warned i n his Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences that "there is no

subject i n w h i c h we must proceed w i t h more caution t h a n i n [history], lest we assign causes w h i c h never existed and reduced what is merely contingent to stable

and universal principles." I n any event, the final balance i n the C o n s t i t u t i o n between the states and the n a t i o n must have come as a great disappointment to Madison, w h i l e H a m i l t o n ' s unitary views are too well k n o w n to need elucidation.

I t is indeed astonishing h o w those w h o have glibly designated James Madison

the "father" of Federalism have overlooked the solid body of fact w h i c h indicates

that he shared H a m i l t o n ' s quest for a unitary central government. T o be specific,

they have avoided examining the clear i m p o r t of the Madison-Virginia Plan, and

have disregarded Madison's dogged i n c h - b y - i n c h retreat from the bastions of centralization. T h e V i r g i n i a Plan envisioned a unitary n a t i o n a l government effectively

freed from and d o m i n a n t over the states. T h e lower house of the national legislature was to be elected directly by the people of the states w i t h membership proport i o n a l to population. T h e upper house was to be selected by the lower and two

John P. Roche

17

chambers would elect the executive and choose the judges. T h e n a t i o n a l government would be thus cut completely loose from the states.

T h e structure of the general government was freed from state control i n a truly

radical fashion, but the scope of the authority of the national sovereign as Madison

initially formulated i t was breathtaking—it was a formulation worthy of the Sage of

Malmesbury himself. T h e national legislature was to be empowered to disallow the

acts of state legislatures, and the central government was vested, i n addition to the

powers of the n a t i o n under the Articles of Confederation, w i t h plenary authority

wherever "the separate States are incompetent or i n w h i c h the harmony of the

U n i t e d States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation." Finally,

just to lock the door against state intrusion, the national Congress was to be given the

power to use military force o n recalcitrant states. This was Madison's " m o d e l " of an

ideal national government, though i t later received little publicity i n The Federalist.

T h e interesting t h i n g was the reaction of the C o n v e n t i o n to this m i l i t a n t program for a strong autonomous central government. Some delegates were startled,

some obviously leery of so comprehensive a project of reform, but nobody set off

any fireworks and nobody walked out. Moreover, i n the two weeks that followed,

the V i r g i n i a Plan received substantial endorsement en principe; the i n i t i a l temper of

the gathering can be deduced from the approval " w i t h o u t debate or dissent," o n

May 3 1 , of the S i x t h Resolution w h i c h granted Congress the authority to disallow

state legislation "contravening in its opinion the A r t i c l e s of U n i o n . " Indeed, an

amendment was included to bar states from contravening n a t i o n a l treaties.

The Virginia Plan may therefore be considered, i n ideological terms, as the delegates' Utopia, but as the discussions continued and became more specific, many of

those present began to have second thoughts. After all, they were n o t residents of

Utopia or guardians i n Plato's Republic w h o could simply impose a philosophical

ideal on subordinate strata of the population. They were practical politicians i n a democratic society, and no matter what their private dreams might be, they had to take

home an acceptable package and defend i t — a n d their o w n political futures—against

predictable attack. O n June 14 the breaking p o i n t between dream and reality took

place. Apparently realizing that under the V i r g i n i a Plan, Massachusetts, V i t g i n i a ,

and Pennsylvania could virtually dominate the national government—and probably

appreciating that to sell this program to "the folks back h o m e " would be impossible—

the delegates from the small states dug i n their heels and demanded time for a consideration of alternatives. One gets a graphic sense of the inner politics from John Dickinson's reproach to Madison: "You see the consequences of pushing things too far.

Some of the members from the small States wish for two branches i n the General Legislature and are friends to a good N a t i o n a l Government; but we would sooner submit

to a foreign power t h a n . . . be deprived of an equality of suffrage i n b o t h branches of

the Legislature, and thereby be t h r o w n under the d o m i n a t i o n of the large States."

T h e bare outline of the Journal entry for Tuesday, June 14, is suggestive to anyone w i t h extensive experience i n deliberative bodies. " I t was moved by M r . Patterson [sic, Paterson's name was one of those consistently misspelled by Madison and

everybody else] seconded by M r . Randolph that the further consideration of the report from the C o m m i t t e e of the whole House [endorsing the V i r g i n i a Plan] be

18

Constitutional Government

postponed t i l l tomorrow and before the question for postponement was taken. I t was

moved by M r . Randolph and seconded by M r . Patterson that the House adjourn."

T h e House adjourned by obvious prearrangement of the two principals: since the

preceding Saturday w h e n Brearley and Paterson of N e w Jersey had announced their

fundamental discontent w i t h the representational features of the V i t g i n i a Plan, the

informal pressure had certainly been building up to slow d o w n the steamroller.

Doubtless there were extended arguments at the I n d i a n Queen between Madison

and Paterson, the latter insisting that events were m o v i n g rapidly towards a probably

disastrous conclusion, towatds a political suicide pact. N o w the ptocess of accommodation was put i n t o action smoothly—and wisely, given the character and strength

of the doubters. Madison had the votes, but this was one of those situations where

the enforcement of mechanical majoritarianism could easily have destroyed the objectives of the majority: the Constitutionalists were i n quest of a qualitative as well

as a quantitative consensus. T h i s was hardly from deference to local Quaker custom;

it was a p o l i t i c a l imperative i f they were to attain ratification.

Ill

A c c o r d i n g to the standard script, at this p o i n t the "states' fights" group intervened i n

force behind the N e w Jersey Plan, w h i c h has been characteristically portrayed as a

reversion to the status quo under the Articles of Confederation w i t h but m i n o r modifications. A careful examination of the evidence indicates that only i n a marginal

sense is this an accurate description. I t is true that the N e w Jersey Plan put the states

back i n t o the institutional picture, but one could argue that to do so was a recognit i o n of political reality rather t h a n an affirmation of states' rights. A serious case can

be made that the advocates of the N e w Jersey Plan, far from being ideological addicts

of states' rights, intended to substitute for the V i r g i n i a Plan a system w h i c h would

b o t h retain strong national power and have a chance of adoption i n the states. T h e

leading spokesman for the project asserted quite clearly that his views were based

more o n counsels of expediency t h a n o n principle; said Paterson o n June 16: " I came

here n o t to speak my o w n sentiments, but the sentiments of those w h o sent me. O u r

object is n o t such a Government as may be best i n itself, but such a one as our C o n stituents have authorized us to prepare, and as they w i l l approve." This is Madison's

version; i n Yates's transcription, there is a crucial sentence following the remarks

above: " I believe that a little practical virtue is to be preferred to the finest theoretical principles, w h i c h cannot be carried i n t o effect." I n his preliminary speech o n

June 9, Paterson had stated " t o the public m i n d we must accommodate ourselves,"

and i n his notes for this and his later effort as well, the emphasis is the same. T h e

structure of government under the Articles should be retained:

2. Because it accords with the Sentiments of the People.

[Proof:] 1. Corns. [Commissions from state legislatures defining the jurisdiction

of the delegates]

2. News-papers—Political Barometer. Jersey never would have sent Delegates under the first [Virginia] P l a n —

Not here to sport Opinions of my own. W t . [What] can be done. A little practical

Virtue preferable to Theory.

John P. Roche

19

This was a defense of political acumen, n o t o f states' rights. I n fact, Paterson's notes

of his speech can easily be construed as an argument for attaining the substantive

objectives of the V i r g i n i a Plan by a sound p o l i t i c a l route, i.e., pouring the new wine

i n the o l d bottles. W i t h a shrewd eye, Paterson queried:

Will the Operation, and Force of the [central] Govt, depend upon the mode of

Representn.—No—it will depend upon the Quantum of Power lodged in the leg.

ex. and judy. Departments—Give [the existing] Congress the same Powers that

you intend to give the two Branches, [under the Virginia Plan] and I apprehend

they will act with as much Propriety and more Energy. . . .

I n other words, the advocates o f the N e w Jersey Plan c o n c e n t r a t e d t h e i r fire

o n what they h e l d t o be t h e political liabilities o f t h e V i r g i n i a P l a n — w h i c h were

matters of i n s t i t u t i o n a l structure—rather t h a n o n t h e proposed scope o f n a t i o n a l

authority. Indeed, the Suptemacy Clause o f the C o n s t i t u t i o n first saw t h e l i g h t

of day i n Patetson's S i x t h Resolution; the N e w Jetsey Plan c o n t e m p l a t e d the use

of m i l i t a r y force t o secure compliance w i t h n a t i o n a l law; a n d f i n a l l y Paterson

made clear his v i e w t h a t undet e i t h e t t h e V i r g i n i a or t h e N e w Jersey systems,

the genetal government w o u l d ". . . act o n individuals and n o t o n states." F r o m

the states' rights v i e w p o i n t , this was heresy: t h e fundament o f t h a t d o c t r i n e was

the proposition t h a t any central g o v e r n m e n t had as its constituents the states,

n o t the people, and c o u l d only reach the people t h r o u g h the agency o f the state

government.

Paterson t h e n reopened the agenda of the C o n v e n t i o n , but he d i d so w i t h i n a

distinctly nationalist framework. Patetson's position was one of favoring a strong

central government i n principle, but opposing one w h i c h i n fact put the big states in

the saddle. ( T h e V i r g i n i a Plan, for a l l its abstract merits, d i d very w e l l by V i r g i n i a . )

As evidence for this speculation, there is a curious and intriguing proposal among

Paterson's preliminary drafts o f the N e w Jersey Plan:

Whereas it is necessary in Order to form the People of the U.S. of America in to a

Nation, that the States should be consolidated, by which means all the Citizens

thereof will become equally intitled to and will equally participate in the same Privileges and Rights. . . it is thetefore resolved, that all the Lands contained within

the Limits of each state individually, and of the U.S. generally be considered as constituting one Body or Mass, and be divided into thirteen or more integral parts.

Resolved, That such Divisions or integral Parts shall be styled Districts.

This makes i t sound as though Patetson was prepared to accept a strong unified central government along the lines of the V i t g i n i a Plan i f the existing states wete eliminated. H e may have gotten the idea from his N e w Jersey colleague Judge D a v i d

Brearley, w h o o n June 9 had commented that the only remedy to the d i l e m m a over

representation was " t h a t a map o f the U.S. be spread out, that all the existing

boundaries be etased, and that a new p a r t i t i o n of the whole be made i n t o 13 equal

parts." A c c o t d i n g to Yates, Btearley added at this point, " t h e n a government o n the

present [Virginia Plan] system w i l l be just."

This proposition was nevet pushed—it was patently unrealistic—but one can

appreciate its purpose: i t would have separated the m e n from the boys i n the largestate delegations. H o w attached would the Virginians have been t o their reform

20

Constitutional Government

principles i f V i r g i n i a were to disappear as a component geographical u n i t (the

largest) for representational purposes? U p to this p o i n t , the Virginians had been i n

the happy position of supporting h i g h ideals w i t h that inner confidence b o r n of

knowledge that the "public interest" they endorsed would nourish their private i n terest. Worse, they had shown l i t t l e willingness to compromise. N o w the delegates

from the small states announced that they were unprepared to be offered up as sacrificial victims to a " n a t i o n a l interest" w h i c h reflected Virginia's parochial ambit i o n . Caustic Charles Pinckney was n o t far off w h e n he remarked sardonically that

"the whole [conflict] comes to this": " G i v e N . Jersey an equal vote, and she w i l l dismiss her scruples, and concur i n the N a t l , system." W h a t he rather unfairly did n o t

add was that the Jersey delegates were n o t free agents w h o could adhere to their private convictions; they had to take back, sponsor and risk their reputations o n the

reforms approved by the C o n v e n t i o n — a n d i n N e w Jersey, n o t i n V i r g i n i a .

Paterson spoke o n Saturday, and one can surmise t h a t over the weekend there

was a good deal of consultation, argument, and caucusing among the delegates. One

member at least prepared a full-length address: o n Monday Alexander H a m i l t o n ,

previously mute, tose and delivered a six-hour o r a t i o n . I t was a remarkably apolitical speech; the gist of his position was that both the V i r g i n i a and N e w Jersey Plans

were inadequately centralist, and he detailed a reform program w h i c h was reminiscent of the Protectorate under the C r o m w e l l i a n Instrument of Government of 1653.

I t has been suggested that H a m i l t o n d i d this i n the best p o l i t i c a l tradition to emphasize the moderate character of the V i r g i n i a Plan, to give the cautious delegates

something really to worry about; but this interpretation seems somehow too clever.

Particularly since the sentiments H a m i l t o n expressed happened to be completely

consistent w i t h those he p t i v a t e l y — a n d sometimes publicly—expressed throughout

his life. H e wanted, to take a striking phrase from a letter to George W a s h i n g t o n , a

"strong w e l l mounted government"; i n essence, the H a m i l t o n Plan contemplated

an elected life monarch, virtually free of public c o n t r o l , o n the Hobbesian ground

that only i n this fashion could strength and stability be achieved. T h e other alternatives, he argued, would put policy-making at the mercy of the passions of the

mob; only i f the sovereign was beyond the reach of selfish influence would i t be possible to have government i n the interests of the whole c o m m u n i t y .

From all accounts, this was a masterful and compelling speech, but (aside from

furnishing John Lansing and Luther M a r t i n w i t h a m m u n i t i o n for later use against

the C o n s t i t u t i o n ) i t made l i t t l e impact. H a m i l t o n was simply transmitting o n a different wavelength from the rest of the delegates; the latter adjourned after his great

effort, admired his rhetoric, and t h e n returned to business. I t was rather as i f they

had taken a day off to attend the opera. H a m i l t o n , never a particularly patient man

or m u c h of a negotiator, stayed for another t e n days and t h e n left, i n considerable

disgust, for N e w York. A l t h o u g h he came back to Philadelphia sporadically and attended the last t w o weeks of the C o n v e n t i o n , H a m i l t o n played no part i n the laborious task of hammering out the C o n s t i t u t i o n . His day came later w h e n he led the

N e w Y o r k Constitutionalists i n t o the savage imbroglio over r a t i f i c a t i o n — a n arena

i n w h i c h his unmatched talent for dirty p o l i t i c a l i n f i g h t i n g may well have w o n the

day. For instance, i n the N e w York Ratifying C o n v e n t i o n , Lansing threw back i n t o

H a m i l t o n ' s teeth the sentiments the latter had expressed i n his June 18 oration i n

John P. Roche

21

the C o n v e n t i o n . However, h a v i n g since retreated to the fine defensive positions

immortalized i n the The Federalist, the C o l o n e l flatly denied that he had ever been

an enemy of the states, or had believed that conflict between states and n a t i o n was

inexorable! As Madison's authoritative Notes d i d n o t appear u n t i l 1840, and there

had been no press coverage, there was n o way to verify his assertions, so i n the

words of the reporter, "a warm personal altercation between [Lansing and H a m i l ton] engrossed the remainder of the day [June 28, 1788]."

IV

O n Tuesday morning, June 19, the vacation was over. James Madison led off w i t h a

long, carefully reasoned speech analyzing the N e w Jersey Plan w h i c h , while intellectually vigorous i n its criticisms, was quite conciliatory i n mood. " T h e great difficulty," he observed, "lies i n the affair of Representation; and i f this could be adjusted,

all others would be surmountable." (As events were to demonstrate, this diagnosis

was correct.) W h e n he finished, a vote was taken o n whether to continue w i t h the

Virginia Plan as the nucleus for a new c o n s t i t u t i o n : seven states voted "Yes"; N e w

York, N e w Jersey, and Delaware voted " N o " ; and Maryland, whose position often depended o n w h i c h delegates happened to be o n the floor, divided. Paterson, i t seems,

lost decisively; yet i n a fundamental sense he and his allies had achieved their purpose: from that day onward, i t could never be forgotten that the state governments

loomed ominously i n the background and that n o verbal incantations could exorcise

their power. Moreover, nobody bolted the C o n v e n t i o n : Paterson and his colleagues

took their defeat i n stride and set to work to modify the V i r g i n i a Plan, particularly

w i t h respect to its provisions o n representation i n the national legislature. Indeed,

they w o n an immediate rhetorical bonus; w h e n O l i v e r Ellsworth of C o n n e c t i c u t rose

to move that the word " n a t i o n a l " be expunged from the T h i r d V i r g i n i a Resolution

("Resolved that a national G o v e r n m e n t ought to be established consisting of a

supreme Legislative, Executive and Judiciary"), Randolph agreed and the m o t i o n

passed unanimously. T h e process of compromise had begun.

For the next t w o weeks, the delegates circled around the problem of legislative

representation. T h e C o n n e c t i c u t delegation appears to have evolved a possible

compromise quite early i n the debates, but the Virginians and particularly Madison

(unaware that he w o u l d later be acclaimed as the prophet of "federalism") fought

obdurately against p r o v i d i n g for equal representation of states i n the second chamber. There was a good deal of acrimony and at one p o i n t B e n j a m i n F r a n k l i n — o f a l l

people—proposed the i n s t i t u t i o n of a daily prayer; practical politicians i n the gathering, however, were meditating more o n the merits of a good committee t h a n o n

the u t i l i t y of D i v i n e i n t e r v e n t i o n . O n July 2, the ice began to break w h e n t h r o u g h a

number of fortuitous events—and one t h a t seems deliberate—the majority against

equality of representation was converted i n t o a dead tie. T h e C o n v e n t i o n had

reached the stage where i t was " r i p e " for a solution (presumably all the therapeutic

speeches had been made), and the South Carolinians proposed a committee. M a d i son and James W i l s o n wanted none of i t , b u t w i t h only Pennsylvania dissenting,

the body voted to establish a working party o n the problem of representation.

22

Constitutional Government

T h e members of this c o m m i t t e e , one from each state, were elected by the

delegates—and a very interesting c o m m i t t e e i t was. Despite the fact that the V i r ginia Plan had h e l d m a j o r i t y support up to t h a t date, neither Madison nor Rand o l p h was selected ( M a s o n was the V i r g i n i a n ) and B a l d w i n of Georgia, whose

shift i n p o s i t i o n had resulted i n the t i e , was chosen. From the composition, i t was

clear t h a t this was n o t to be a " f i g h t i n g " c o m m i t t e e : the emphasis i n membership

was o n w h a t m i g h t be described as "second-level p o l i t i c a l entrepreneurs." O n the

basis of the discussions up to t h a t t i m e , o n l y L u t h e t M a r t i n of M a r y l a n d could be

described as a "bitter-ender." A d m i t t e d l y , some d i v i n a t i o n enters i n t o this sort of

analysis, but one does get a sense of the m o o d of the delegates from these

c h o i c e s — i n c l u d i n g the interesting selection of B e n j a m i n F r a n k l i n , despite his

age and i n t e l l e c t u a l wobbliness, over the b r i l l i a n t and incisive W i l s o n ot the

sharp, polemical Gouverneur M o r r i s , to represent Pennsylvania. His passion fot

c o n c i l i a t i o n was more valuable at this j u n c t u r e t h a n Wilson's logical genius, or

Morris's acerbic w i t .

There is a c o m m o n rumor that the framers divided their time between philosophical discussions of government and reading the classics i n p o l i t i c a l theory. Perhaps this is as good a t i m e as any to note that their concerns were highly practical,

that they spent l i t t l e time canvassing abstractions. A number of them had some acquaintance w i t h the history of p o l i t i c a l theory (probably gained from reading John

Adams's m o n u m e n t a l c o m p i l a t i o n A Defense of the Constitutions of Government, the

first volume of w h i c h appealed i n 1786), and i t was a poor rhetorician indeed who

could n o t cite Locke, Montesquieu, or H a r r i n g t o n in support of a desired goal. Yet

up to this p o i n t i n the deliberations, n o one had expounded a defense of states'

rights or the "separation of powers" o n a n y t h i n g resembling a theoretical basis. I t

should be reiterated that the Madison model had no r o o m either for the states or for

the "separation of powers": effectively all governmental power was vested i n the nat i o n a l legislature. T h e merits of Montesquieu d i d n o t t u r n up u n t i l The Federalist;

and although a perverse argument could be made that Madison's ideal was truly i n

the t r a d i t i o n of John Locke's Second Treatise of Government, the Locke w h o m the

A m e r i c a n rebels treated as an honorary president was a pluralistic defendet of

vested rights, n o t of parliamentary supremacy.

I t w o u l d be tedious to continue a blow-by-blow analysis of the w o t k of the delegates; the critical fight was over representation of the states and once the Connecticut Compromise was adopted o n July 17, the C o n v e n t i o n was over the hump.

Madison, James W i l s o n , and Gouverneur Morris of N e w York (who was there representing Pennsylvania!) fought the compromise all the way i n a last-ditch effort to

get a unitary state w i t h parliamentary supremacy. But their allies deserted t h e m and

they demonstrated after their defeat the essential opportunist character of theit

objections—using "opportunist" here i n a nonpejorative sense, to indicate a w i l l ingness to swallow their objections and get o n w i t h the business. Moreover, once

the compromise had carried (by five states to four, w i t h one state divided), its advocates threw themselves vigorously i n t o the job of sttengthening the genetal government's substantive powers—as m i g h t have been predicted, indeed, from Paterson's

early statements. I t nourishes an increased respect for Madison's devotion to the art

of politics, to realize that this dogged fighter could sit d o w n six months latet and

John P. Roche

23

prepare essays for The Federalist i n c o n t r a d i c t i o n to his basic convictions about the

true coutse the C o n v e n t i o n should have taken.

V

Two tricky issues w i l l serve t o illustrate the later process of accommodation. T h e

first was the institutional position of the Executive. Madison argued for an executive

chosen by the national legislature and o n May 29 this had been adopted w i t h a provision that after his seven-year term was concluded, the chief magistrate should n o t

be eligible for reelection. I n late July this was reopened and for a week the matter

was argued from several different points of view. A good deal of desultory speechmaking ensued, but the gist of the problem was the opposition from t w o sources to

election by the legislature. O n e group felt that the states should have a hand i n the

process; another small but influential circle urged direct election by the people.

There were a number of proposals: election by the people, election by state governors, by electors chosen by state legislatures, by the national legislature (James W i l son, perhaps ironically, proposed at one p o i n t that an Electoral College be chosen by

lot from the national legislature!), and there was some resemblance t o threedimensional chess i n the dispute because of the presence of t w o other variables,

length of tenure and reeligibility. Finally, aftet opening, reopening, and re-reopening

the debate, the thorny problem was consigned t o a committee for absolution.

The Brearley Committee o n Postponed Matters was a superb aggregation of talent and its compromise o n the Executive was a masterpiece of political improvisation.

(The Electoral College, its creation, however, had l i t t l e i n its favot as an institution—

as the delegates well appreciated.) T h e p o i n t of departure for all discussion about the

presidency i n the C o n v e n t i o n was that i n immediate terms, the problem was nonexistent; i n other words, everybody present knew that under any system devised, George

Washington would be President. Thus they were dealing i n the future tense and t o a

body of wotking politicians the merits of the Brearley proposal were obvious: everybody got a piece of cake. ( O r to put i t more academically, each viewpoint could leave

the C o n v e n t i o n and argue to its constituents that i t had really w o n the day.) First, the

state legislatures had the right to determine the mode of selection of the electors; second, the small states received a bonus i n the Electoral College i n the form of a guaranteed m i n i m u m of three votes while the big states got acceptance of the principle of

proportional power; t h i t d , i f the state legislatures agreed (as six did i n the first presidential election), the people could be involved directly i n the choice of electors; and

finally, i f no candidate received a majority i n the College, the right of decision passed

to the national legislature w i t h each state exercising equal strength. ( I n the Brearley

recommendation, the election went to the Senate, but a m o t i o n from the floor substituted the House; this was accepted o n the ground that the Senate already had enough

authority over the executive i n its treaty and appointment powers.)

This compromise was almost too good to be true, and the framers snapped i t up

w i t h l i t t l e debate o t controversy. N o one seemed to t h i n k w e l l of the College as an

institution; indeed, what evidence there is suggests that there was an assumption

that once W a s h i n g t o n had finished his tenure as President, the electors would

24

Constitutional Government

cease t o produce majorities and the C h i e f Executive would usually be chosen i n the

House. George Mason observed casually that the selection would be made i n the

House nineteen times i n twenty and n o one seriously disputed this p o i n t . T h e v i t a l

aspect of the Electoral College was that i t got the C o n v e n t i o n ovet the hurdle and

protected everybody's interests. T h e future was left to cope w i t h the problem of

what t o do w i t h this Rube Goldberg mechanism.

I n short, the framers d i d n o t i n their wisdom endow the U n i t e d States w i t h a

college of Cardinals—the Electoral College was n e i t h e t an exercise i n applied Platonism nor an experiment i n indirect government based o n elitist distrust of the

masses. I t was merely a jerry-rigged improvisation w h i c h has subsequently been endowed w i t h a h i g h theoretical content. W h e n an elector from O k l a h o m a i n 1960

refused t o cast his vote for N i x o n ( n a m i n g Byrd and Goldwater instead) o n the

ground that the Founding Fathers intended h i m to exercise his great independent

wisdom, he was indulging i n historical fantasy. I f one were t o indulge i n counterfantasy, he would be tempted t o suggest t h a t the Fathers would be startled to f i n d

the College still i n operation—and perhaps even dismayed at their descendants'

lack of judgment or inventiveness.

T h e second issue o n w h i c h some substantial practical bargaining took place was

slavery. T h e morality of slavery was, by design, n o t at issue; but i n its other concrete

aspects, slavery colored the arguments over taxation, commerce, and representation.

T h e "Three-Fifths Compromise," that three-fifths of the slaves would be counted

b o t h for representation and for purposes of direct taxation ( w h i c h was drawn from

the past—it was a formula of Madison's utilized by Congress i n 1783 to establish the

basis of state contributions t o the Confederation treasury), had allayed some N o r t h ern fears about Southern overrepresentation (no one t h e n foresaw the trivial role

that direct taxation would play i n later federal financial policy), but doubts still remained. T h e Southerners, o n the othet hand, were afraid that Congressional cont r o l over commerce would lead to the exclusion of slaves or to their excessive taxat i o n as imports. Moreover, the Southerners were disturbed over "navigation acts,"

i.e., tariffs, or special legislation providing, for example, that exports be carried only

i n A m e r i c a n ships; as a section depending u p o n exports, they wanted protection

from the p o t e n t i a l voracity of their commercial brethren of the Eastern states. T o

achieve this end, Mason and others urged that the C o n s t i t u t i o n include a proviso

that navigation and commercial laws should require a two-thitds vote i n Congress.

These problems came t o a head i n late August and, as usual, were handed to a

committee i n the hope that, i n Gouverneur Morris's words, "these things may form

a bargain among the N o r t h e r n and Southern States." T h e Committee repotted its

measures of r e c o n c i l i a t i o n o n August 25, and o n August 29 the package was

wrapped up and delivered. W h a t occurred can best be described i n George Mason's

dour version (he anticipated C a l h o u n i n his c o n v i c t i o n that permitting navigation

acts to pass by majority vote w o u l d p u t the South i n economic bondage t o the

N o r t h — i t was mainly o n this ground that he refused to sign the C o n s t i t u t i o n ) :

The Constitution as agreed to till a fortnight befote the Convention rose was such a

one as he would have set his hand and heart to. . . . [Until that time] The 3 New

England States were constantly with us in all questions . . . so that it was these

three States with the 5 Southern ones against Pennsylvania, Jersey and Delaware.

John P. Roche

25

With respect to the importation of slaves, [decision-making] was left to Congress.

This disturbed the two Southern-most States who knew the Congress would immediately suppress the importation of slaves. Those two States therefore struck up a

bargain with the three New England States. If they would join to admit slaves for

some years, the two Southern-most States would join in changing the clause which

required the 2/3 of the Legislature in any vote [on navigation acts]. It was done.

O n the floor o f the C o n v e n t i o n there was a v i r t u a l love-feast o n this happy occasion. Charles Pinckney o f S o u t h C a r o l i n a a t t e m p t e d t o o v e r t u r n t h e c o m m i t tee's decision, w h e n the compromise was reported t o the C o n v e n t i o n , by insisting that the S o u t h needed p r o t e c t i o n f r o m t h e imperialism o f t h e N o r t h e r n

states. B u t his S o u t h e r n colleagues were n o t prepared t o rock the boat and G e n eral C. C . Pinckney arose t o spread o i l o n t h e suddenly ruffled waters; he admitted that:

It was in the true interest of the S[outhern] States to have no regulation of commerce; but considering the loss brought on the commerce of the Eastern States by

the Revolution, their liberal conduct towards the views of South Carolina [on the

regulation of the slave ttade] and the interests the weak Southn. States had in being united with the strong Eastern states, he thought it proper that no fetters

should be imposed on the power of making commercial regulations; and that his

constituents, though prejudiced against the Eastern States, would be reconciled to this liberality. He had himself prejudices against the Eastern States before he came here,

but would acknowledge that he had found them as liberal and candid as any men

whatever. (Italics added.)

Pierce Butler took the same tack, essentially arguing that he was n o t too happy

about the possible consequences, but that a deal was a deal. M a n y Southern leaders

were l a t e r — i n the wake o f the " T a r i f f of A b o m i n a t i o n s " — t o rue this day of reconciliation; Calhoun's Disquisition on Government was little more t h a n an extension o f

the atgument i n the C o n v e n t i o n against p e r m i t t i n g a Congressional majority t o enact navigation acts.

VI

Drawing o n their vast collective p o l i t i c a l experience, utilizing every weapon i n the

politician's arsenal, looking constantly over their shoulders at their constituents,

the delegates put together a C o n s t i t u t i o n . I t was a makeshift affair; some sticky issues (for example, the qualification o f voters) they ducked entirely; others they

mastered w i t h that ancient instrument o f p o l i t i c a l sagacity, studied ambiguity (fot

example, citizenship); and some they just overlooked. I n this last category, I suspect, fell the matter of the power o f the federal courts to determine the constitutionality o f acts o f Congress. W h e n the judicial article was formulated ( A r t i c l e I I I

of the C o n s t i t u t i o n ) , deliberations were still i n the stage whete the legislature was

endowed w i t h broad power under the R a n d o l p h formulation, authority w h i c h by its

o w n tetms was scarcely amenable to judicial review. I n essence, courts could hardly

determine w h e n " t h e separate States are incompetent or . . . the harmony o f the

U n i t e d States may be interrupted"; the national legislature, as critics p o i n t e d out,

26

Constitutional Government

was free to define its o w n jurisdiction. Later the d e f i n i t i o n of legislative authotity

was changed i n t o the form we k n o w , a series of stipulated powers, but the delegates

never seriously reexamined the jurisdiction of the judiciary under this new limited formulation. A l l arguments o n the i n t e n t i o n of the framers i n this matter are thus deductive

and a posteriori, t h o u g h some obviously make more sense t h a n others.

T h e framers were busy and distinguished men, anxious to get back to their families, their positions, and their constituents, n o t members of the French Academy

devoting a lifetime to a dictionary. T h e y were trying to do an important job, and do

it i n such a fashion that their h a n d i w o r k would be acceptable to very diverse constituencies. N o one was rhapsodic about the final document, but i t was a beginning,

a move i n the right d i r e c t i o n , and one they had reason to believe the people would

endorse. I n addition, since they had modified the impossible amendment provisions

of the A r t i c l e s (the tequirement of u n a n i m i t y w h i c h could always be ftustrated by

"Rogues Island") to one demanding approval by only three-quarters of the states,

they seemed confident that gaps i n the fabric w h i c h experience would reveal could

be rewoven w i t h o u t undue difficulty.

So w i t h a neat phrase introduced by B e n j a m i n F r a n k l i n (but devised by

Gouverneur M o t t i s ) w h i c h made t h e i t decision sound unanimous, and an inspired

benediction by the O l d Doctor urging doubters to doubt t h e i t o w n infallibility, the

C o n s t i t u t i o n was accepted and signed. Curiously, Edmund Randolph, w h o had

played so v i t a l a role throughout, refused to sign, as d i d his fellow V i r g i n i a n George

Mason and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts. Randolph's behavior was eccentric, to

say the least—his excuses for refusing his signature have a factitious ring even at

this late date; the best explanation seems to be that he was afraid that the Constitut i o n w o u l d prove to be a liability i n V i r g i n i a politics, where Patrick H e n r y was

burning up the countryside w i t h impassioned denunciations. Ptesumably, Randolph

wanted to check the temper of the populace before he risked his reputation, and

perhaps his job, i n a fight w i t h b o t h H e n r y and Richard Henry Lee. Events lend

some justification to this speculation: after m u c h temporizing and use of the condit i o n a l subjunctive tense, Randolph endorsed ratification i n V i r g i n i a and ended up

getting the best of b o t h worlds.

Madison, despite his reservations about the C o n s t i t u t i o n , was the campaign

manager i n ratification. His first task was to get the Congress i n N e w York to light

its o w n funeral pyre by approving the "amendments" to the Articles and sending

t h e m o n to the state legislatures. A b o v e a l l , m o m e n t u m had to be maintained. T h e

anti-Constitutionalists, n o w thoroughly alarmed and n o novices i n politics, tealized that their best tactic was a t t r i t i o n rather t h a n direct opposition. Thus they settled o n a position expressing qualified approval but calling for a second Convent i o n to remedy various defects (the one w i t h the most demagogic appeal was the

lack of a B i l l of Rights). Madison knew that to accede to this demand would be

equivalent to losing the battle, nor w o u l d he agree to c o n d i t i o n a l approval (despite

wavering even by H a m i l t o n ) . T h i s was an all-or-nothing proposition: national salv a t i o n o t n a t i o n a l impotence w i t h no intermediate positions possible. Unable to

get Congressional approval, he settled for second best: a unanimous resolution of

John P. Roche

27

Congress transmitting the C o n s t i t u t i o n to the states for whatever action they saw

fit to take. T h e opponents t h e n moved from N e w York and the Congress, where

they had attempted to attach amendments and conditions, to the states for the f i nal battle.

A t first the campaign for ratification went beautifully: w i t h i n eight months aftet the delegates set their names to the document, eight states had ratified. O n l y i n

Massachusetts had the result been close ( 1 8 7 - 1 6 8 ) . Theoretically, a ratification by

one more state c o n v e n t i o n would set the new government i n m o t i o n , but i n fact

u n t i l V i r g i n i a and N e w York acceded to the new U n i o n , the lattet was a f i c t i o n .

N e w Hampshire was the next to ratify; Rhode Island was i n v o l v e d i n its characteristic p o l i t i c a l convulsions (the legislature there sent the C o n s t i t u t i o n out to the

towns for decision by popular vote and i t got lost among a series of local issues);

N o r t h Carolina's c o n v e n t i o n d i d n o t meet u n t i l July and t h e n postponed a final decision. This is hardly the place for an extensive analysis of the conventions of N e w

York and V i r g i n i a . Suffice i t to say that the Constitutionalists clearly outmaneuvered their opponents, forced t h e m i n t o impossible p o l i t i c a l positions, and

w o n b o t h states narrowly. T h e V i r g i n i a C o n v e n t i o n could serve as a classic study i n

effective floor management: Patrick H e n r y had to be contained, and a teading of

the debates discloses a standard two-stage technique. H e n r y w o u l d give a four- or

five-hour speech denouncing some section of the C o n s t i t u t i o n o n every conceivable ground (the federal district, he averred at one p o i n t , w o u l d become a haven for

convicts escaping from state a u t h o r i t y ! ) ; w h e n H e n r y subsided, " M r . Lee of Westmoreland" would rise and literally poleax h i m w i t h sardonic invective ( w h e n H e n r y

complained about the m i l i t i a power, "Lighthorse H a r r y " really punched below the

belt: observing that while the fotmet Governor had been sitting i n R i c h m o n d duting the R e v o l u t i o n , fie had been out i n the trenches w i t h the troops and thus felt

bettet qualified to discuss military affairs). T h e n the gentlemanly Constitutionalists

(Madison, Pendleton, and Marshall) w o u l d pick up the matters at issue and examine them i n the light of reason.

Indeed, modern Americans w h o tend to t h i n k of James Madison as a rather

desiccated character should spend some time w i t h this transcript. Probably Madison

put o n his most spectacular demonstration of n i m b l e thetotic i n what m i g h t be

called " T h e Battle of the Absent A u t h o r i t i e s . " Patrick H e n r y i n the course of one

of his harangues alleged that Jefferson was k n o w n to be opposed to Virginia's approving the C o n s t i t u t i o n . T h i s was clever: H e n r y hated Jefferson, but was ptepated

to use any weapon that came to hand. Madison's riposte was superb: First, he said

that w i t h all due respect to the gteat reputation of Jeffetson, he was n o t i n the

countty and therefore could n o t formulate an adequate judgment; second, n o one

should utilize the reputation of an outsider—the V i r g i n i a C o n v e n t i o n was there to

t h i n k for itself; t h i t d , i f there were to be recourse to outsidets, the opinions of

Geotge Washington should certainly be taken i n t o consideration; and finally, he

knew from privileged personal communications from Jefferson that i n fact the lattet

strongly favored the C o n s t i t u t i o n . T o devise an assault route i n t o this rhetotical

fortress was literally impossible.

28

Constitutional Government

VII

T h e fight was over; all that remained n o w was to establish the new frame of government i n the spirit of its framers. A n d w h o were bettet qualified fot this task t h a n

the framers themselves? Thus victory for the C o n s t i t u t i o n meant simultaneous victory for the Constitutionalists; the anti-Constitutionalists either capitulated or vanished i n t o limbo—soon Patrick H e n r y w o u l d be offered a seat o n the Supreme

C o u r t and Luther M a r t i n w o u l d be k n o w n as the Federalist "bull-dog." A n d irony

of ironies, Alexander H a m i l t o n and James Madison w o u l d shortly accumulate a

reputation as the formulators of what is often alleged to be our p o l i t i c a l theory, the

concept of "federalism." Also, o n the other side of the ledger, the arguments would

soon appear over what the framers "really meant"; w h i l e these disputes have assumed the proportions of a big scholarly business i n the last century, they began almost before the i n k o n the C o n s t i t u t i o n was dry. O n e of the best early ones featured H a m i l t o n versus Madison o n the scope of presidential power, and other

framers characteristically assumed positions i n this and other disputes o n the basis

of their p o l i t i c a l convictions.

Probably our greatest difficulty is that we k n o w so m u c h more about what the

framers should have meant t h a n they themselves d i d . W e are intimately acquainted

w i t h the problems that their C o n s t i t u t i o n should have been designed to master; i n

short, we have read the mystery story backwards. I f we are to get the right "feel" for

their time and their circumstances, we must i n Maitland's phrase, " t h i n k ourselves

back i n t o a t w i l i g h t . " Obviously, n o one can pretend completely to escape from the

solipsistic web of his o w n environment, but if the effort is made, i t is possible to appreciate the past roughly o n its o w n terms. T h e first step i n this process is to abandon

the academic premise that because we can ask a question, there must be an answer.

Thus we can ask what the framers meant w h e n they gave Congress the power to

regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and we emerge, reluctantly perhaps, w i t h

the reply that they may n o t have k n o w n what they meant, that there may n o t have

been any semantic consensus. T h e C o n v e n t i o n was n o t a seminar i n analytic philosophy or linguistic analysis. Commerce was commerce—and if different interpretations

of the word arose, later generations could worry about the problem of definition. T h e

delegates were i n a hurry to get a new government established; when definitional arguments arose, they characteristically took refuge i n ambiguity. I f different men voted

for the same proposition for varying reasons, that was politics (and still is); if later

generations were unsettled by this lack of precision, that would be their problem.

There was a good deal of definitional pluralism w i t h respect to the problems

the delegates d i d discuss, but w h e n we move to the question of extrapolated i n t e n tions, we enter the realm of spiritualism. W h e n m e n i n our time, for instance,

launch i n t o elaborate talmudic exegesis to demonstrate that federal aid to parochial

schools is (or is n o t ) i n accord w i t h the intentions of the m e n w h o established the

Republic and endorsed the B i l l of Rights, they are engaging i n historical ExttaSensory Perception. ( I f one were to j o i n this E.S.P. contingent for a minute, he

m i g h t suggest that the hard-boiled politicians w h o wrote the C o n s t i t u t i o n and B i l l

of Rights w o u l d chuckle scornfully at such an i n v o c a t i o n of authority: obviously a

p o l i t i c i a n w o u l d chart his course o n the intentions of the l i v i n g , n o t of the dead,

and count the number of Catholics i n his constituency.)

John P. Roche

29

T h e C o n s t i t u t i o n , t h e n , was n o t an apotheosis of "constitutionalism," a t r i umph of architectonic genius; i t was a patch-work sewn togethet under the pressure

of b o t h time and events by a group of extremely talented democratic politicians.

They tefused to attempt the establishment of a strong, centralized sovereignty o n

the ptinciple of legislative suptemacy for the excellent reason that the people w o u l d

not accept i t . They risked their p o l i t i c a l fortunes by opposing the established doctrines of state sovereignty because they weie convinced that the existing system was

leading to national impotence and probably foreign d o m i n a t i o n . For t w o years, they

worked to get a c o n v e n t i o n established. For over three months, i n what must have

seemed to the faithful participants an endless process of give-and-take, they reasoned, cajoled, threatened, and bargained amongst themselves. T h e result was a

C o n s t i t u t i o n w h i c h the people, i n fact, by democratic processes, d i d accept, and a

new and fat better national government was established.

Beginning w i t h the inspired propaganda of H a m i l t o n , Madison, and Jay, the

ideological build-up got under way.The Federalist had l i t t l e impact o n the ratificat i o n of the C o n s t i t u t i o n , except perhaps i n N e w York, but this volume had enormous influence o n the image of the C o n s t i t u t i o n i n the minds of future generations, particulatly o n historians and p o l i t i c a l scientists w h o have an innate fondness

for theoretical symmetry. Yet, w h i l e the shades of Locke and Montesquieu may

have been hovering i n the background, and the delegates may have been unconscious instruments of a ttanscendent telos, the careful observer of the day-to-day

work of the C o n v e n t i o n finds n o overarching principles. T h e "separation of powers" to h i m seems to be a by-product of suspicion, and "federalism" he views as a pis

aller, as the farthest p o i n t the delegates felt they could go i n the destruction of state

power w i t h o u t themselves i n v i t i n g repudiation.

T o conclude, the C o n s t i t u t i o n was neither a victory for abstract theory nor a

great practical success. W e l l ovet h a l f a m i l l i o n m e n had to die o n the battlefields

of the C i v i l W a r before certain constitutional principles could be defined—a baleful consideration w h i c h is somehow overlooked i n our customary ttibutes to the farsighted genius of the framers and to the supposed A m e r i c a n talent for "constitutionalism." T h e C o n s t i t u t i o n was, however, a v i v i d demonstration of effective

democratic p o l i t i c a l action, and of the forging of a n a t i o n a l elite w h i c h literally

persuaded its countrymen to hoist themselves by their o w n boot straps. A m e t i c a n

pro-consuls w o u l d be wise n o t to translate the C o n s t i t u t i o n i n t o Japanese, or

Swahili, or treat i t as a w o r k of semi-Divine origin; but w h e n students of comparative politics examine the process of n a t i o n - b u i l d i n g i n countries newly freed from

colonial rule, they may f i n d the A m e t i c a n experience instructive as a classic example of the potentialities of a democratic elite.

r*a

John Roche's article on the framing of the Constitution was written as an attack upon a

variety of views that suggested the Constitution was not so much a practical political

document as an expression of elitist views based upon political philosophy and economic

interests. One such elitist view was that of Charles A. Beard, who published his famous An

Economic Interpretation of the Constitution in 1913. He suggested that the Constitution

30

Constitutional Government

was nothing more than the work of an economic elite that was seeking to preserve its