PDF Viewing archiving 300 dpi

advertisement

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

----------------------------------------------------- x

In re:

Chapter 11

ENRON CORP., et al.,

Case No. 01-16034 (AJG)

Debtors.

Jointly Administered

----------------------------------------------------- x

REPORT OF NEAL BATSON, COURT-APPOINTED EXAMINER, IN

CONNECTION WITH THE EXAMINATION OF NATIONAL ENERGY

PRODUCTION CORPORATION PURSUANT TO COURT ORDER

DATED DECEMBER 6, 2002

April 7, 2003

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1

A.

Overview

1

B.

Issues Addressed in this Report

3

C.

Summary of Conclusions .....•........................................................................... 5

II.

NEPCO AND ITS ROLE IN ENRON'S CASH MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

A.

NEPCO Entities and the NEPCO Business

B.

Enron's Cash Management System

C.

NEPCO's Participation in the CMS

D.

Circumstances Surrounding NEPCO's Participation in the CMS

E.

TracingNEPCO's Cash

~

14

14

18

23

26

31

III. NEPCO'S POST-PETITION ACTIONS

A.

Impact ofEnron's Bankruptcy Filing

B.

SNC-Lavalin Transaction

37

37

40

IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A.

Conclusions

B.

Recommendations

42

42

43

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

Exhibit 3

Enron Cash Management System Accounts

NEPCO Cash Receipts by Month, 2001

NEPCO Cash Receipts by Customer, 2001

AppendixA-

Applicable Legal Standards

I.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A.

Overview

On May 20, 2002, National Energy Production Corporation (''NEPCO''), an

indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Enron Corp. ("Enron"), and certain of its

subsidiaries and related companies (collectively, the ''NEPCO Debtors")! filed voluntary

petitions for relief under Chapter 11 of Title 11 of the United States Code (the

"Bankruptcy Code") with the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of

New York (the "Court"). The NEPCO Debtors sought joint administration of their cases

with the Chapter 11 case previously filed by Enron on December 2, 2001 (the "Enron

Petition Date").

In connection with the filing of the NEPCO Debtors' bankruptcy petitions, the

NEPCO Debtors submitted an affidavit of their ChiefExecutive Officer, G. Brian Stanley

(the "Stanley Affidavit"). The Stanley Affidavit stated that the NEPCO Debtors had been

rendered insolvent, in part, because $360 million had been "swept,,2 from the NEPCO

Debtors' bank account into Enroncontrolled bank accounts pursuant to Enron's cash

management system (the "CMS").3 Following the NEPCO Debtors' bankruptcy filings,

certain customers of the NEPCO Debtors and creditors of such customers (collectively,

the "Claimants") filed various pleadings with the Court asserting, among other things,

that the NEPCO Debtors had been injured by the cash sweep into the CMS and that the

1 The NEPCO Debtors are: (i) NEPCO, (ii) two ofNEPCO's wholly owned subsidiaries, NEPCO Power

Procurement Company (''NPPC'') and NEPCO Services International, Inc. ("NSII") and (iii) Enron Power

& Industrial Construction Company ("EPIC"), an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of NEPCO's direct

parent, Enron Engineering & Construction Company ("EE&CC").

The terms "sweep" and "swept" can be used in various ways. In this Report, the Examiner will use the

terms "sweep" and "swept" to refer to the process by which cash was transferred into and throughout

Enron'scash management system.

2

3

Stanley Affidavit ~ 20.

NEPCO Debtors, or the Claimants as subrogees of the NEPCO Debtors, should be

permitted to assert a constructive trust4 over the swept cash. Furthermore, certain of the

Claimants requested that the Court appoint a trustee or an examiner to investigate the

issues related thereto.

By Order dated October 7, 2002 (the "October i

h

Order"), the Court ordered the

appointment of an examiner to address the issues raised by the Claimants.

The

October 7th Order also provided that Neal Batson (the "Examiner"), who previously had

been appointed by the Court to investigate, among other things, the use by Enron of

special purpose vehicles,S would serve as the examiner to investigate certain of the issues

raised by the Claimants. The Examiner, at the direction of the Court, submitted his

recommendation regarding the structure and scope of his investigation. 6 By Order dated

December 6, 2002 (the "December 6th Order"), the Court approved the Examiner's

4 Under applicable law, to assert a constructive trust the putative beneficiary must show: (i) fraud or a

breach of a fiduciary duty or confidential relationship; (ii) unjust enrichment of the putative trustee, and

(iii) specific identification of the property as to which a trust should be imposed. A more detailed

discussion of constructive trusts is included in Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards) attached hereto.

By Order dated April 8, 2002 (the "April 8th Order"), the Court had authorized and directed the

appointment of an examiner, pursuant to 11 U.S.C. § 1104(c), to investigate, inter alia, the use by Emon of

special purpose vehicles (or entities created or structured by Emon or at the behest ofEmon) (the "SPEs")

in connection with its finances. On Mal 22, 2002, the United States Trustee appointed Neal Batson as the

Examiner contemplated by the April 8 Order. The Court, by Order dated May 24, 2002, approved the

United States Trustee's appointment of Neal Batson as Examiner. To date, the Examiner has submitted

two interim reports pursuant to the April 8th Order.

5

On November 11,2002, the Examiner submitted the Recommendation of Neal Batson, Court-Appointed

Examiner, with Respect to Scope and Time Frame of the Examination Pursuant to Court Order Dated

October 7, 2002 (the "Initial Recommendation"), Docket No. 7747; and on December 4, 2002, the

Examiner submitted the Supplemental Recommendation of Neal Batson, Court-Appointed Examiner, with

Respect to Scope and Time Frame of the Examination Pursuant to the Court's Order Dated October 7,2002

(the "Supplemental Recommendation"), Docket No. 8192.

)

6

-2-

recommendation regarding the scope of his investigation and directed the Examiner to

investigate Enron's acquisition and use ofNEPCO's cash through the CMS.?

B.

Issues Addressed in this Report

This report (the "Report,,)8 addresses the following issues specifically

recommended by the Examiner and adopted in the December 6th Order:

1.

the amounts and timing of sweeps of cash generated by NEPCO

(''NEPCO Cash") into the CMS;

2.

the sources of the NEPCO Cash swept into the CMS;

3.

the disposition of the swept cash by Enron, including the location

of deposits and the details of its use, if any;

4.

whether the swept NEPCQ Cash can be traced;

5.

whether any fraud, dishonesty, incompetence, misconduct,

mismanagement or irregularity by NEPCO or Enron occurred in

connection with the cash sweeps; and

6.

whether the factual and legal predicates for the imposition of a

constructive trust for the amount of the cash swept by Enron may

be asserted by NEPCO.

This Report does not address: (i) the ability of a particular Claimant to assert

claims against theNEPCO Debtors or Enron; (ii) the ability of the Claimants to assert a

7 Order Approving the Supplemental Recommendation of Neal Batson, the Court-Appointed Examiner,

with Respect to Scope and Time Frame of the Examination Pursuant to the Court's Order Dated October 7,

2002, Docket No. 8235.

8 Any references in this Report to meetings, communications, contacts, and actions between the Examiner

and third parties are intended to refer to the office of the Examiner, which shall include the Examiner and

his professionals. Therefore, references to any meetings, communications, contacts and actions taking

place between the Examiner and a third party should not be construed as indicating that Neal Batson was

present personally for such meetings, communications, contacts or actions.

"

-3-

statutory trust against NEPCO or through NEPCO against Enron;9 or (iii) issues

concerning the post-petition sale of certain assets of the NEPCO Debtors or other postpetition conduct ofthe NEPCO Debtors, Enron or third-parties. Io

Although technically possible to confme the analysis in this Report to the NEPCO

Debtors, the Examiner believes that such analysis would by its very nature be an

incomplete analysis ofNEPCO's business .and the sources and uses of the NEPCO Cash.

Therefore, this Report will sometimes refer to the term "NEPCO Entities" which

collectively refers to the NEPCO Debtors and three related entities. These related entities

are: (i) Thai NEPCO Co., Ltd. ("Thai NEPCO"), a wholly owned subsidiary of

NEPCO; II (ii) Pakistan Construction Services, Inc. ("Pakistan NEPCO"), a wholly

owned subsidiary of EE&CC; 12 and (iii) NEPCO Procurement Company ("NPC"), a

division of Enron Equipment Procurement Company, .an indirect wholly owned

subsidiary of Enron. 13 The seven entities comprising theNEPCO Entities were the

In this regard, the Examiner has not undertaken to discuss the possible claims by contractors (or any

subrogee of the contractors) under applicable state law with respect to the imposition of a statutory trust

against either NEPCO or Enron. The law of certain states may authorize, in limited circumstances, the

holders of mechanics' liens or similar claims to assert statutory trust claims; however, the Examiner has

concluded that this potential theory of recovery is creditor specific and does not affect the analysis of the

relationship between NEPCOas putative constructive trust beneficiary and Enron as putative constructive

trust trustee.

9

10 The Examiner's recommendation proposed, among other things, that the examination be conducted in

stages. The first stage would analyze NEPCO's ability to assert a constructive trust over the funds it

deposited into the CMS. Later stages, to be undertaken only after further direction from the Court, would

analyze the rights of specific Claimants to assert a constructive or other trust against NEPCO or Enron, and

other issues raised by Claimants related to the post-petition actions of NEPCO and Enron, including the

$NC Transaction (as dermed below).

11 Thai NEPCO was formed to construct two power generation facilities in Thailand. It was dOrmarIt in

2001.

12 Pakistan NEPCO was established to construct a power generation facility in Pakistan. It was effectively

dormant in 2001.

13 NPC was established after Enron purchased NEPCO. It procured many ofthe large equipment items for

NEPCO projects. In 2001, NPC did not have any cash receipts, but approximately $250 million was

disbursed from the CMS on its behalf, all related to projects undertaken by NEPCO.

)

-4-

entities through which NEPCO's business was operated. I4

These related entities

undertook all of their operations on behalf of NEPCO by perfonning services and

providing goods to NEPCO that enabled NEPCO to satisfy its contractual obligations to

its customers. Thus, all cash transactions conducted between NEPCO and such related

companies were treated by Enron and NEPCO's management as NEPCO related

transactions and were reflected in the inter-company balances on both Enron's and

NEPCO's financial accounts and records. I5 NEPCO is the only NEPCO Entity that

contributed any cash into the CMS during 2001. The Examiner has concluded that

NEPCO is the only NEPCO Entity that could attempt to impose a constructive trust

against Enron.

Accordingly, this Report discusses NEPCO's ability to impose a

constructive trust rather than the ability of other NEPCO Entities to impose such a trust.

C.

Summary of Conclusions

As set forth more fully below, the Examiner has reached the following

conclusions:

(i)

The amounts and timing ofsweeps ofNEPCO Cash into the CMS

NEPCO's cash collections were swept into the CMS each day by the transfer of

its collections from an account at Bank of America into an Enron controlled step account,

and then into a single concentration account used by Enron to accumulate the daily cash

14 Telephone Interview with George Brian Stanley, former Chief Executive Officer, NEPCO, by David M.

Maxwell and Atiqua Hashem, Alston & Bird LLP, March 10,2003 (the "Stanley Interview"); In-Person

Interview with John Gillis, former President, NEPCO, and Steve Daniels, former Vice President, Busirless

Development, NEPCO, by David M. Maxwell and Atiqua Hashem, Alston & Bird LLP, Feb. 19,2003 (the

"Gillis/Daniels Interview").

15 NEPCO

Combirled Trial Balance [AB0507 00760-AB0507 00761].

November

-5-

2001

[AB0507 00757-AB0507 0075~]

and

receipts of Enron and its subsidiaries. I6 The funds in the Bank of America concentration

account were wire transferred daily to a disbursement concentration account at Citibank:,

N.A. ("Citibank") used by Enron to pay its obligations and the obligations of its

subsidiaries, including the NEPCO Entities.

The total amount of NEPCO Cash transferred into the CMS for the period from

January 1, 2001 17 through November 30, 2001 was $1.720 billion. Is For the same period,

the CMS supplied $1.401 billion to pay the NEPCO Entities' operating expenses and

other obligations. The difference, $319 million, represents the net cash contribution by

NEPCO to the CMS during 2001. 19

This net increase in NEPCO's contribution to the CMS is reflected in the

combined inter-company receivable balance in NEPCO's 2001 financial statements. The

net receivable grew from $83 million at the end of 2000 to $388 million at the end of

November 2001. 20 The increase of $305 million equals the net contribution of cash by

NEPCO ($319 million), less $14 million of inter-company assessments. NEPCO's net

16 NEPCO's initial collections account, the step account into which it was swept, and the corporate

collections concentration account into which the step account was swept were all accounts maintained at

Bank of America, N.A ("Bank of America").

17 The Examiner has focused his analysis in this Report on 2001, the year prior to the Enron Petition Date,

because, among other reasons, approximately eighty percent (80%) of the inter-company balance between

NEPCO and Enron was generated in 2001. Furthermore, analysis of prior years would not affect the

ultimate conclusions in this Report.

18 Analysis of Examiner's Accounting Professionals (the "Accounting Professionals' Analysis")

[AB050701345].

19 NEPCO could theoretically assert that it should be able to trace the entire $1.720 billion that NEPCO

contributed to the CMS during this period and ignore the $1.401 billion of funds that the NEPCO Entities

received during this period. That is, there should not be any "netting" of the amounts placed into the CMS

by NEPCO against the benefit received by the NEPCO Entities. The Examiner is unaware of any

published decisions that address this issue. However, the Examiner has concluded that this position is

untenable in the context of a constructive trust because it ignores the critical unjust enrichment component

that is at the essence of this equitable remedy.

NEPCO Combined Trial Balance - Year End 2000 [AB0507 00763-AB0507 00764] and

[AB0507 00766-AB0507 00767]; NEPCO Combined Trial Balance - November 2001 [AB050700757AB0507 00758] and [AB0507 00760-AB0507 00761].

)

20

-6-

cash contribution in 2001, and the resulting increase in its receivable balance from Enron,

is detailed below:

Cash Transactions

NEPCO Cash into CMS

$1.720 billion

Payments by CMS on NEPCO Entities' behalf $1.401 billion

$ 319 million

Net Cash Contribution

Inter-Company NEPCO Receivable Impact

Beginning Net Receivable Balance

Ending Net Receivable Balance

$ 83 million

$388 million

Net increase in Receivable Balance

$30S-million

Inter-Company Assessments21

$ 14 million

Total Cash Impact to Receivable Balance

$319 million

Although there was an increase in the inter-company receivable from January 1, 2001 to

the Enron Petition Date, for the period from September 12, 2001 through the Enron

Petition Date, the NEPCO Entities actually were net consumers of cash from the CMS in

an amount exceeding $57 million. That is, they received approximately $57 million of

cash from the CMS in excess of NEPCO Cash contributed to the CMS during such

time. 22

(ii)

The sources ofthe NEPCO Cash swept into the CMS

The $1.720 billion of NEPCO Cash swept into the CMS in 2001 was received

from two sources: (i) $1.547 billion from domestic customer payments to NEPCO under

lump sum engineering, procurement and construction contracts ("EPC contracts")

2\

These consist of non-cash transactions for assessed taxes, overhead and other indirect expenses.

22 $455 million ofNEPCO Cash was swept into the CMS but $512 million came from the eMS to satisfy

obligations of the NEPCO Entities. Accounting Professionals' Analysis [AB0507 01356]. The Examiner

has analyzed in detail the period between September 12, 2001 and the Enron Petition Date because on

September 12, 2001 the entire CMS was in a cash negative position by more than $200 million. See

discussion below regarding how NEPCO's ability to impose a constructive trust may be extinguished by

this negative cash position.

-'

-7-

between NEPCO and its customers,23 and (ii) $173 million from receipts related to an

international power plant project in Brazi1?4 Of the $1.720 billion of receipts in 2001,

the Examiner has tracked $1.702 billion, or 99%, to seventeen specific domestic

construction projects and the above-referenced Brazilian power plant. 25 Each of these

receipts was collected in response to invoices generated by NEPCO when specific,

identifiable and agreed upon milestones in its EPC contracts were achieved.

(iii)

The disposition of the swept .cash by Enron, including the

location ofdeposits and the details o/its use, if any

NEPCO Cash was used in the same manner as cash received from all of the other

Enron subsidiaries that participated in the CMS. It was swept into the CMS through

various layers of consolidation accounts at Bank of America, all controlled by Enron,

and then wire transferred to a single Enron owned and controlled disbursement

concentration account at Citibank. From the Citibank concentration account, the funds

were used to pay the current obligations of Enron and its subsidiaries. The CMS funds

were used, in part, to pay the expenses and obligations of the NEPCO Entities as those

obligations became due. 26 In 2001, approximately $1.4 billion of funds were paid by the

CMS on behalf of the NEPCO Entities. Each NEPCO account in the CMS is identified

in the diagram in Section II.C. ofthis Report.

In-Person Interview with Robert Cranmer, former Chief Financial Officer, NEPCO, by David M.

Maxwell and Atiqua Hashem, Alston & Bird LLP, Feb. 20, 2003 (the "Cranmer Interview"); Stanley

Interview.

23

24 The $173 million was deposited into the accounts ofNEPCO's direct parent, EE&CC, but was treated as

funds ofNEPCO and credited to NEPCO's combined inter-company receivable balance.

The remaining I% consists of numerous small deposits. While these deposits were not traced to a

specific project, there is no indication that the deposits came from sources other than those identified

above.

25

Each disbursement from the Citibank concentration account, and each of the step and specific

disbursement accounts below it, may be tracked by payee, but to do so would necessitate an audit of each

such account. Such an audit would be expensive and the analysis would not affect the Examiner's

conclusions in this Report. Therefore, the Examiner did not undertake suchan audit.

-'

26

-8-

(iv)

Whether the swept NEPCO Cash can be traced

The NEPCO Cash swept into the CMS can be traced, usmg the lowest

intennediate balance rule,27 into several different accounts in the CMS. However, there

are three notable facts that the Examiner believes will effectively prohibit or limit

significantly NEPCO's ability to satisfy the tracing element in order to establish a

constructive trust. They are:

•

On September 12, 2001, the CMS was, on an aggregate basis, in a cash

negative position of approximately $238 million (the "September 1ih

Negative Balance").

•

Between September 12, 2001 and the Enron Petition Date, the NEPCO

Entities were net consumers of cash from the CMS of approximately $57

million (the ''Net Consumer Status,,).28

•

On November 30,2001, the CMS, on an aggregate basis, was reduced to

approximately $56.3 million, of which only approximately $23 million

was potentially NEPCO Cash (the "November 30th Minimal Balance").

The September 12th Negative Balance eliminates any res as of that date. After

that date, the Net Consumer Status eliminates any basis to claim unjust enrichment. The

November 30th Minimal Balance indicates that even if any res did survive after

September 12, 2001 and even if there had been unjust enrichment, the value of such res

would not exceed approximately $23 million.

The lowest intermediate balance rule is used to trace trust funds that are commingled with non-trust

funds ina bank account. The rule assumes that trust funds are the last funds to be removed from a

commingled account, there1;>y making the trust identifiable as long as the balance in the account remains

above the value of the trust. A more detailed discussion of constructive trusts and this tracing rule is

included in Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards) attached hereto.

27

The $57 million was calculated by aggregating the payments made by the CMS during this period to

satisfy the obligations of all of the NEPCO Entities. As discussed above, all NEPCO Cash was paid

directly by NEPCO's customers into NEPCO's cash collections account, discussed below, which was part

of the CMS. During this period, cash was disbursed by the CMS on behalf of all of the NEPCO Entities.

All of these cash disbursements on behalf of the NEPCO Entities were related to NEPCO's business

operations and were made on account of obligations for which NEPCO was primarily obligated under an

EPC contract. As a result, the Examiner believes that aggregating these payments is appropriate in

analyzing the ability of NEPCO to impose a constructive trust because this approach accords with the

critical unjust enrichment component that is the essence of the equitable remedy of a constructive trUst.

28

-9-

The Examiner notes that there are several judgments to be made in connection

with analyzing the foregoing facts for which there are no published decisions directly on

point and, as a result, there may be a contrary view.29 However, as discussed more fully

below, despite the lack of direct authority, the Examiner has analyzed these issues under

general equitable principles of tracing to reach his conclusions.

In addition, there may be another avenue available to NEPCO to trace funds - if

NEPCO was permitted to trace funds to Enron related accounts external to the CMS?O If

permitted to do this, there may be additional funds available over which NEPCO could

attempt to assert a constructive trust. Attempting to trace the cash through the eMS and

into other non-CMS accounts, or other Enron assets, would be time consuming,

uncertain3l and extremely expensive. Given the difficulties surrounding NEPCO's ability

to establish the other elements of a constructive trust as discussed in this Report, the

Examiner does not recommend undertaking such an audit.

They are: (i) whether there can be a netting of amounts contributed into the CMS by NEPCOagainst

amounts received by the NEPCO Entities out of the CMS and (ii) whether it is appropriate to use the

aggregate amount of cash in the CMS to determine, at a point in time, if the res has been extinguished

(e.g., where the concentration disbursement account has a negative cash position that is so large that on an

aggregate basis the CMS is in a negative cash position even though there are positive amounts of cash in

the other applicable CMS accounts).

29

In Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards), the Examiner discusses the reported cases addressing the

application of the lowest intermediate balance rule to trace funds where there are multiple accounts. No

case is directly on point. However, in Majutama v. Drexel Burnham Lambert Group, Inc. (In re Drexel

Burnham Lambert, Inc.), 142 B.R. 623 (S.D.N.Y. 1992), the bankruptcy court, in addition to allowing the

plaintiff to conduct discovery concerning the principal account into which the funds allegedly subject to a

constructive trust were deposited, also allowed the plaintiff to conduct discovery concerning other accounts

of the defendant. The bankruptcy court refused to permit discovery of transfers into accounts of

independent subsidiary corporations of the defendant/debtor. However, on appeal, the district court

affIrmed the grant of summary judgment in favor of the debtor, holding that once the plaintiffs' funds

disappeared from the initial account, the tracing had to stop. If this Court were to permit NEPCO to

attempt to trace funds into accounts outside the CMS, the attempt would require an audit of each Enron

account worldwide to determine fIrst if commingled CMS funds came into the account, and if so, whether

the lowest intermediate balance rule would enable NEPCO to assert a trust over any or all remaining funds

in the subject account. The Examiner's accountants estimate that such an audit would take approximately

six to eight months and cost between $2 and $5 million.

30

31

See Section II.E. below for a discussion of the uncertainties and complexities associated with such an

)

un&m~g.

-10-

(v)

Whether anyfraud, dishonesty, incompetence, misconduct,

mismanagement or irregularity by NEPCO or Enron occurred in

connection with the cash sweeps

The Examiner has found no evidence of fraud, negligence or other malfeasance

with regard to NEPCO's participation in the CMS or in connection with the sweep of

NEPCO Cash into the CMS.NEPCO appears to have participated in Enron's CMS in the

same manner and to the same extent as substantially all other wholly owned domestic

Enron affiliates. In addition, there does not appear to have been any change in the CMS,

or NEPCO's participation in the CMS, in the months prior to the Enron Petition Date.

Furthermore, there is no indication that (i) either NEPCO or Enron accelerated cash

collections or delayed cash payments on behalf of NEPCO (or otherNEPCO Entities),

prior to the Enron Petition Date32 or (ii) Enron forced or pressured NEPCO to enter into

EPC contracts as a financing tool for Enron.

(vi)

Whether the factual and legal predicates for the imposition

of a constructive trust for the amount of the NEPCO Cash

swept by Enron may be asserted by NEPCO

The requisite elements for the imposition of a constructive trust by NEPCO over

the funds swept to Enron via the CMS do not appear to be present. 33 Specifically, in

order to prevail in asserting a constructive trust against Enron, NEPCO must demonstrate

each of the following:

(i) fraud or a breach of a fiduciary duty or confidential

relationship; (ii) Enron was unjustly enriched, and (iii) NEPCO can trace its funds into

identifiable accounts in the possession of Enron. 34

As noted above, the NEPCO Entities enjoyed a Net Consumer Status for the period from September 12,

2001 through the Emon Petition Date in excess of$57 million.

32

As discussed in Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards), bankruptcy courts generally look to relevant

state law to determine the elements necessary to establish a constructive trust.

33

34

See Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards).

-11-

None of these elements appear to be present. As noted above, the Examiner has

found no evidence of fraud, negligence or other malfeasance by either NEPCO or Enron

with respect to the CMS.

In addition, it is unlikely that NEPCO will be able to

demonstrate that Enron owed it a fiduciary duty merely because Enron was its ultimate

parent, or that there is any other basis for finding a fiduciary relationship or one of special

confidence or trust. Nor is it likely thatNEPCO will be able to demonstrate that a

fiduciary or similar duty owed to it by Enron, to the extent one existed, was breached as a

result of the operation of the CMS. Enron's CMS was

e~tablished

before it acquired

NEPCO, the CMS had a legitimate corporate purpose, and it does not appear that NEPCO

was treated differently under the CMS than any other domestic wholly owned affiliate of

Enron that participated in the CMS.

It also is unlikely that Enron was unjustly enriched by the CMS. During 2001, the

NEPCO Entities did contribute more to the CMS than they had taken out: they made a

net cash contribution of $319 million to the eMS as of the Enron Petition Date.

However, the mere fact of a positive cash balance, without more, does not appear to meet

the "unjust enrichment" standard required under the law for the imposition of a

constructive trust.

Moreover, NEPCO would be required to identify specific property, in this

instance bank account funds, over which it could assert a constructive trust. As discussed

above, the September 12th Negative Balance would extinguish any res as ofthat date, and

the Net Consumer Status of the NEPCO Entities after September 12, 2001 would

eliminate any claim of unjust enrichment. Furthermore, assuming arguendo NEPCO is

able to establish a res after September 12, 2001, and assuming arguendo some unjust

-12-

enrichment occurred after that date, the November 30th Minimal Balance limits NEPCO's

potential res to a maximum amount of $23 million.

-13-

II.

NEPCO AND ITS ROLE IN ENRON'S CASH MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

A.

NEPCO Entities and the NEPCO Business

NEPCO was in the business of constructing large power generation facilities in

the United States and, to a lesser extent, overseas. 35 NEPCO engineered and built, on a

turnkey basis, electric power plants for its customers, and had been in this business for

many years. 36

Enron purchased NEPCO in 1997 from Zum Industries, Inc. ("Zurn,,).37 Once

affiliated with Enron,38 NEPCO was able to pursue and obtain substantially more and

larger projects. This primarily was a result of Enron's ability to guarantee NEPCO's

perfonnance on its projects. 39 Accordingly, from 199840 to 2001, the aggregate revenues

35

Stanley Interview; GillislDaniels Interview.

NEPCO first began operation in 1938 as Bumstead-Woolford. Paul Nyhan, Enron Subsidiary Nepco

Cuts 40 from Bothell Work Force, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Reporter, April 25, 2002, at Dl, available at

http://seattlepi.nwsource.comlbusiness/67864 nepc025.shtml.

36

37 Letter from Zum Industries, Inc. to Enron Corp. dated Oct. 20, 1997 (accepting post-closing adjustment

in purchase price pursuant to Purchase and Sale Agreement dated July 31, 1997) [AB0276 00441~

AB0276 00442].

Initially, NEPCO was a wholly owned subsidiary of EE&CC, which in turn was a wholly owned

subsidiary of Enron. During 2001, as Enron restructured its operations, different Enron entities were given

operational responsibility for NEPCO. In March 2001, Enron announced the formation of a new

corporation, Enron Engineering and Operational Services Company ("EEOS"), which included NEPCO,

EE&CC and a third entity, Operational Energy Corporation. In September 2001, Enron announced the

formation of Enron Global Services ("EGS") and EEOS (along with NEPCO) thereafter reported to EGS.

Stanley Interview.

38

Despite these organizational changes, the individuals responsible for NEPCO's day-to-day operations

rernainedconstant. John Gillis, who had been President of NEPCO since Enron acquired the company

from Zum in 1997, continued as President. Mr. Gillis reported to the Chief Operating Officer ofEE&CC,

who for most of2001 was Keith Dodson. Mr. Dodson in turn reported to G. Brian Stanley, who was Chief

Executive Officer ofEE&CC and thenEEOS until early 2002.

Enron's guarantees enabled NEPCO to obtain more and larger projects than it previously had been able

to obtain. The guarantees gave customers, who otherwise would have required external bonding for the

project, the security they required. Deposition of Timothy J. Detmering, Managing Director of Corporate

Development, Enron Corp. by Mark N. Parry, Moses & Singer LLP, Aug. 23, 2002, at 60, lines 19-25, In

re Enron Corp., et al., C.A. No. 01-16034 (AJG) (Bankr. S.D.N.Y.) (the "Detmering Depo., at _ , lines

39

-").

40

1998 is the first full year NEPCO was affiliated with Enron.

-14-

of NEPCO (and the other NEPCO Entities) increased from $202 million to more than

$2.2 billion.41

NEPCO entered into EPC contracts with the owners of the plants to be

constructed by NEPCO. The EPC contracts provided for payments by the owners based

upon a negotiated and agreed series of milestones set forth in detail in the contract. 42

When a milestone was achieved (e.g., when the foundation of a building was completed),

NEPCO submitted an invoice to its customer. Generally, the customer employed an

independent engineer to review the progress of construction and make an independent

assessment of whether the specific milestone had in fact been achieved. Additionally,

when a project was financed by a lender, the lender's own independent engineer would

often monitor the construction process and review invoices. Once an invoice received the

necessary approvals, the customer paid NEPCO. 43

NEPCO and the other NEPCO Entities paid vendors and subcontractors as

supplies were delivered or work was performed on the various projects. These payments

were made on behalf of the NEPCO Entities out of the CMS. Ensuring that sufficient

funds are available to pay the vendors and subcontractors is a major part of a contractor's

business risk. Accordingly, contractors generally attempt to frontload their contracts to

ensure that they have received sufficient funds from their customer to cover the costs

41 NEPCO Combined Trial Balance - Year End 1998 IAB0507 00748]; NEPCO Combined Trial Balance

- November 2001 [AB0507 00756] and [AB0507 00759].

See Section 7.4, Turnkey Engineering, Procurement and Construction Agreement by and between

Ouachita Power, LLC as Owner, and National Energy Production Corporation as Contractor dated as of

June 27, 2003 (the "Ouachita EPC Contract") [AB0294 00297-AB0294 00423].

42

See Section 6.03(a), Amended and Restated Turnkey Engineering, Procurement and Construction

Agreement for Combined-Cycle Generation Facility between Panda Gila River, L.P. and National Energy

Production Corporation dated as of April 30, 2001 but effective as of Feb. 28, 2001 [AB0283 00484AB0283 00599].

)

43

-15-

owed to suppliers and vendors as those invoices come due. 44 Absent this frontloading, a

contractor could find itself "loaning" money to its customers by paying suppliers before it

had been paid. 45

NEPCO thus attempted to frontload its contracts to ensure that

sufficient cash had come in from its customers to keep it in a cash positive position as the

vendors and subcontractors were paid.46

The milestone payments, then, did not

necessarily represent a reimbursement for or prepayment of actual expenditures by

NEPCO at any given time.

Instead, these payments were the product of advance

negotiations regarding how much the customer would pay for completion of the specific

milestone.

NEPCO established, on occasion, wholly owned subsidiaries through which it

conducted business.

Specifically, NPPC was established as the purchasing ann of

NEPCO in an effort to minimize certain sales and use tax expenses, and NSII was

established to staff international projects for NEPCO. 47 Also, NEPCO's direct parent

corporation, EE&CC, established EPIC to provide union labor in connection with one

NEPCO project in Oregon. 48 In addition, Thai NEPCO was formed to construct two

44 In-Person Interview with David Hattery, In-House Counsel at Enron Corp. assigned to work on NEPCO

matters, by David M. Maxwell and Atiqua Hashem, Alston & Bird LLP, Feb. 19,2003 (the "Hattery

Interview"). See John D. Hastie, "Architectural and Construction Contracts - The Developer's

Perspective," R18l ALI-ABA 1731, 1731 (June 28, 1993).

This was especially problematic for a contractor in NEPCO's line of business where the vendor's

invoice could be in the tens of millions of dollars. See Ouachita EPC Contract at Exhibit E - Project

Milestone Payment Schedule (frrst progress payment on a gas turbine shown as $54,731,980).

45

46

Hattery Interview.

In-Person Interview with Keith Marlow, former Chief Financial Officer, EE&CC, by David M. Maxwell

and Atiqua Hashem, Alston & Bird LLP, Feb. 18,2003 (the "Marlow Interview"); Corporate Data Sheet:

NSII [AB0647 00020-AB0647 00022].

47

48

Marlow Interview.

-16-

power generation facilities in Thailand. 49 It was dormant in 2001. 50 Pakistan NEPCO

was established to construct a power generation facility in Pakistan. It was effectively

dormant in 2001; no cash was received by or disbursed on behalf of Pakistan

Construction Services, Inc. in 2001, there was, however, one tax assessment adjustment

of approximately $500,000 in 2001. 51 Finally, NPC was a division of Enron Equipment

Procurement Company, an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Enron.

NPC was

established after NEPCO was purchased by Enron in 1997.52 It procured many of the

large equipment items for NEPCO projects. As NEPCOgrew, NEPCO established its

own purchasing company, NPPC.

After this date, NPC and NPPC appear to have

continued to be used for procurement by NEPCO. 53 In 2001, approximately $250 million

of purchases by NPC were paid out of funds from the CMS. 54 All of these purchases ~

i.e., all of these CMS funds ~ were related to NEPCO projects. 55 Moreover, although

NPC was not owned by the same direct parent as the NEPCO Debtors,NEPCO and

Enron management treated NPC as part of NEPCO for management and financial

reporting purposes. 56

49

Corporate Data Sheet: Thai NEPCO [AB0647 00017-AB0647 00019].

Marlow Interview; NEPCO Combined Trial Balance - November 2001 [AB050700756] and

[AB050700759].

50

51

NEPCO Combined Trial Balance - November 2001 [AB0507 00756] and [AB0507 00759].

52

Stanley Interview.

53

Stanley Interview.

54

Accounting Professionals' Analysis [AB0507 01347].

55

!d.

56

Stanley Interview; NEPCO Combined Trial Balance - November 2001 [AB050700756] and

[AB050700759].

)

-17-

B.

Enron's Cash Management System

Enron, like many large United States corporations, utilized a centralized system of

cash management in order to maximize its investment yield on its cash position and

minimize its cost of borrowing. 57 Additionally, the centralization of cash management

permitted increased control over the cash thereby minimizing the risk of malfeasance or

negligence with respect to such cash. Enron required that substantially all of its wholly

owned domestic subsidiaries participate in the CMS.58 The CMS was in place before

Enron acquired NEPCO.59

In-Person Interview with Mary Perkins, Vice President, Financial Support and Assistant Treasurer,

Enron Corp., by Dennis J. Connolly and David M. Maxwell, Alston & Bird LLP, Jan. 29, 2003 (the

"Perkins January 29 Interview"); Telephone Interview with Mary Perkins, Vice President, Financial

Support and Assistant Treasurer, Enron Corp., by David M. Maxwell and Atiqua Hashem, Alston & Bird

LLP, March 12, 2003 (the "Perkins March 12 Interview").

57

Perkins January 29 Interview; Perkins March 12 Interview. See also "Enron Minimum Cash Control

Standards," Oct. 2000 (showing "policy will apply to all entities and joint ventures where Enron Corp.

directly or indirectly owns greater than 50% of the voting rights of the entity") (the "Enron Treasury

Policy") [AB0295 0003G-AB0295 00043].

58

59

Perkins January 29 Interview.

-18-

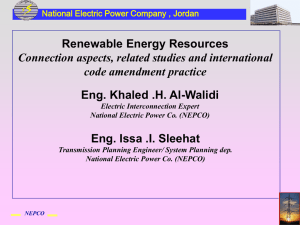

The structure of Enron's CMS is outlined in the following diagram:

ENRON CMS PROCESS

COMMERCIAL

PAPER

J.P. MORGAN

OVERNIGHT

INVESTMENT

CITffiANK

BANK OF AMERICA

PAYROLL

COLLECTIONS

CONCENTRATION

ACCOUNT

DISBURSEMENTS

CONCENTRATION

ACCOUNT

OTHER

USES

STEP

DISBURSEMENT

ACCOUNT

BUSINESS

SPECIFIC

COLLECTIONS

ACCOUNT

BUSINESS

SPECIFIC

COLLECTIONS

ACCOUNT

BUSINESS

SPECIFIC

COLLECTIONS

ACCOUNT

STEP

DISBURSEMENT

ACCOUNT

BUSINESS

SPECIFIC

ACCOUNT

BUSINESS

SPECIFIC

ACCOUNT

BUSINESS

SPECIFIC

COLLECTIONS

ACCOUNT

The CMS structure consisted of numerous accounts at two banks: Bank of America and

Citibank, with Bank of America providing the collection accounts and Citibank providing

the disbursement accounts.

Under the Enron Treasury Policy, Enron affiliates were

instructed to open a collections account at Bank of America and to direct their customers

to make payments to that account. 60 At the close of each business day, the funds in the

60

Enron Treasury Policy; Perkins January 29 Interview; Perkins March 12 Interview.

-19-

collections accounts were transferred by a zero balancing transaction61 into a specific

"step" account, also at Bank of America. In general, the step accounts were established

for each of Enron's business units or groups of businesses in similar industries. 62 From

the step accounts the cash funds were zero balanced into a single concentration account at

Bank of America for Enron and substantially all of its subsidiaries.

The funds in the Bank of America concentration account were wire transferred

each day to a single disbursement concentration account at Citibank. Funds from other

sources, including proceeds from Enron's daily borrowings, also were deposited into this

disbursement concentration account at Citibank. 63

The funds in the disbursement

concentration account were used in a wide variety of ways.

obligations were paid directly from this account.

Enron'scorporate

The obligations of participating

affiliates (including the NEPCO Entities) were paid from lower level disbursement step

accounts. These disbursement step accounts were "daylight overdraft" zero balancing

Zero balancing can consist of either removing funds from an account to bring its balance to zero or, if

applicable, depositing funds into an account to bring its balance to zero. As a practical matter, unless an

unusual circumstance occurred (e.g., a misdirected wire transfer) both the NEPCO collections account and

the step account were always positive at the end of a day and thus, in order to be zero balanced, those funds

would be moved into the concentration account.

61

62

Perkins January 29 Interview.

Prior to October 24, 2001, Enron's working capital borrowings consisted primarily of sales of

commercial paper. After that date it no longer had the ability to sell commercial paper in the market and

consequently made drawings under its $3 billion of revolving lines of credit. These lines of credit

consisted of a 364-day revolving credit agreement in an amount up to $1.750 billion and a longer term

revolving credit agreement in an amount up to $1.250 billion. These lines were made available by a

syndicate of fInancial institutions with Citibank serving as Administrative Agent (collectively, the

"Revolving Credit Lines") [AB0507 00467-AB 0507 00474]. Perkins January 29 Interview.

63

-20-

accounts64 that at the close of each day were zero balanced with the Citibank

concentration account.

The CMS was driven each day by decisions made by Enron's Treasury

Department. Each morning the Treasury Department would analyze the expected cash

receipts and the expected cash needs for that day in order to "set" Enron's cash position.

Once this position was set - i.e., once it was determined how much cash Enron would

need on a given day and how much borrowing or repaying of debt would be necessary to

achieve that position65

-

the Treasury Department began to move cash to and from

various accounts as needed. Generally, Enron was a "net borrower" and it was required

to borrow each day to fund its operations. 66

The Treasury Department monitored the cash position throughout the day. If it

became apparent that the cash position as set earlier in the day was in error, the Treasury

Department either would obtain more funds or utilize the excess funds. 67 If additional

funding was needed, and time permitted, Enron would sell additional commercial paper.

If time did not permit additional commercial paper to be sold, Enron had access to its two

64 A daylight overdraft account is an account from which the bank permits disbursements even though

funds are not in the account, as long as the funds are deposited into the account at the close of the day.

Accordingly, Emon's daylight overdraft step disbursement accounts were used each day to pay obligations

as they came due; at the close of each business day each account zero balanced with the Citibank

concentration account by taking from that account sufficient funds to cover that day's disbursements.

65 The position was "set" by approximately 10:00 each morning at which time a borrowing or payment

decision was made by the Treasury Department. Once a decision to borrow or repay funds was made by

the Treasury Department, it was not reversible that day. Perkins January 29 Interview.

In-Person Interview with Mary Perkins, Vice President Financial Support and Assistant Treasurer,Emon

Corp. by David M. Maxwell, Alston & Bird LLP, Jan. 9, 2003 (the "Perkins January 9 Interview"); Perkins

March 12 Interview.

66

67

Perkins January 9 Interview.

-21-

Revolving Credit Lines, totaling $3 billion. 68 If, on the other hand, Enron had more cash

at the end of the day than it had estimated, it either would repay its commercial paper

debt iftime permitted or invest the funds. 69

Thus, at the end of a given day if the Treasury Department had estimated the

receipts and uses of cash accurately, Enron would have a zero balance in its cash

management system ~ it would effectively have used all of that day's receipts, borrowed

only as much as was necessary to meet its obligations and ended with a balance at or near

zero. As a practical matter, this was an impossibility. Estimating the anticipated receipts

on a given day was especially difficult.

It was generally easier to estimate the

disbursements because Enron had control over whether or not it would disburse its cash;

however, Enron had no control over whether its customers would payor whether they

would pay timely.

Once the Treasury Department had made its receipts estimate, it would wire

transfer funds from the Bank of America concentration account to the Citibank

concentration account. 70

Of course, on occasion, errors occurred and the Treasury

Department moved more money from the Bank of America concentration account than

actually carne into that account on a given day. When this occurred, the Bank of America

concentration account was overdrawn and Bank of America would, in effect, make a

Enron did not draw upon its Revolving Credit Lines until October 25, 2001 when it borrowed the entire

amount of each line. The full amount of the Revolving Credit Lines remained outstanding as of the Enron

Petition Date. Perkins January 9 Interview; Perkins January 29 Interview.

68

69 Enron preferred to repay outstanding borrowings rather than invest because it believed that repayment

generated a higher return. Perkins January 9 Interview; Perkins January 29 Interview.

As noted above., this generally occurred at approximately midmorning each day. If the amount to be

wire transferred was sufficiently large, Enron would divide it into several smaller transfers. Perkins

March 12 Interview.

70

-22-

"loan" to Enron equal to the amount of overdrawn funds. 71 More often, however, there

was a remaining balance in the Bank of America collections account at the end of a given

day.

This amount was transferred by Bank of America into an overnight off-shore

investment account in Nassau, the Bahamas. The principal and overnight interest earned

was redeposited into the Bank of America concentration account the next morning.

A similar process took place at Citibank. At the conclusion of .each day, any

funds remaining in the concentration account were transferred and invested by Citibank

in an off-shore overnight investment account. The following morning the principal along

with the interest earned was redeposited into the Citibank concentration account. 72

The specific bank accounts linked to the CMS changed as Enron's business

changed; accounts were added and deleted as needed. The identity of the accounts

connected to the eMS as ofNovember 30, 2001 is set forth in the attached Exhibit 1.

C.

NEPCO's Participation in the CMS

Enron required NEPCO to participate in the CMSY Under the Enron Treasury

Policy, for all practical purposes, substantially all of Enron's domestic wholly owned

subsidiaries were required to participate in the CMS. 74 In addition, NEPCO did not have

the accounting personnel, equipment or wherewithal to operate independent of a

71 Enron attempted to avoid this situation because the interest expense on the overdrawn funds was Enron's

highest cost of borrowing. Perkins January 9 Interview; Perkins January 29 Interview.

72

Perkins January 9 Interview.

73

Marlow Interview; Enron Treasury Policy, at 2.

74

Perkins January 9 Interview; Enron Treasury Policy, at 2.

-23-

centralized cash management systemY Indeed, prior to Enron's acquisition of NEPCO

from Zum, NEPCO had participated in Zum's centralized cash management system. 76

NEPCO'scash was deposited into the CMS via a series of zero balancing

accounts, described above, that automatically removed cash from the NEPCO collections

account and consolidated that cash into larger accounts within the CMS. 77

75 See "Financial Analysis and Reporting Project" draft of Arthur Andersen, dated Sept. 2001, at 2 (noting

that a full time Chief Financial Officer and staff of project accountants did not exist at NEPCO)

[AB0279 01423-AB0279 01427]; GillislDaniels Interview.

76

GillislDaniels Interview.

77

Perkins January 9 Interview.

-24-

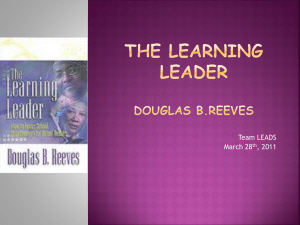

The structure of the NEPCO Entities account participation within the CMS is

shown in the diagram below.

NEPCO CMS ACCOUNT STRUCTURE

Bank of America

Citibank

Enron Corp

Overnight

Investment

Account

t

EnronCorp

Overnight

Investment

Account

JP Morgan Chase

(Clearing Agt)

Commercial Paper

Settlement Account

t

#144000763

I

EnronCorp

Receipt

Concentration

Account

#3750494015

....

~

Enron Corp

Disbursement

Concentration

Account

#3751311977

(owned by Enron

Corp.)

Various other

EE&CC

Accounts

#3751311948

Outside Investments

(Merrill Lynch,

Goldman Sachs,

etc.)

t

EE&CC

disbursement

account for wire

transfers

EnronCorp

Citibank Delaware

Payroll

Transactions

#40807423

#3910-9855

t

i i

NEPCO

Collections

Account

....

....

#00076486

i

EE&CCCash

Services Account

~

EE&CC

disbursement

account for

check writing

#3861181

NEPCO's receipts were deposited into NEPCO's collections account, Account

No. 3751311948, at Bank of America?8

Each day the collections account was

consolidated by a zero balancing transaction into step Account No. 3751311977 at Bank

78

Perkins March 12 Interview.

-25-

of America. 79 This step account was itself zero balanced and consolidated, along with

other step accounts, into the corporate-wide cash concentration account at Bank: of

America, Account No. 3750494015.

Once the NEPCO funds were in the Bank: of

America concentration account they were transferred, along with other commingled

funds, to Enron's disbursement concentration account, Account No. 00076486, at

Citibank:.

From the Citibank: concentration account, the commingled funds were used by the

Enron Treasury Department as described in the previous section. That is, the applicable

NEPCO Entity's obligations were paid out of the CMS from one of two EE&CC step

disbursement accounts at Citibank:: Account No. 40807423 was used for wire transfers

and Account No. 386118180 was used for check payments. In sum, NEPCO's cash was

taken into the CMS, and the applicable NEPCO Entity's obligations were paid out of the

CMS, in the same way as substantially all other domestic wholly owned Enron affiliates.

D.

Circumstances Surrounding NEPCO's Participation in the CMS

Participation Consistent with Prior Practice

NEPCO's participation in the CMS in the months preceding the Enron Petition

Date was consistent with its previous participation in the eMS. NEPCO continued to

invoice its customers for milestone payments, collect those payments in its Bank: of

America collections account, allow those funds to be swept into the CMS each day as

part of the zero balancing activities, and obtain from the CMS payment of its current

obligations and obligations of the applicable NEPCO Entity.

79

Bank of America account number 3751311977 was a step accountfor all EE&CC transactions.

The EE&CC check writing account, Account No. 3861181, was not linked directly to the Citibank

concentration account. Rather, it was linked to the EE&CC wire transfer account, Account No. 40807423,

which in tum was linked to the concentration account.

80

-26-

No Attempt to Improperly Accelerate Collections or Delay Payments

It is clear that both Enron's management and NEPCO's management were aware

in 2001 of Enron's favorable cash position with respect to NEPCO. Indeed, in the

summer of 2001, this issue was an impediment to Enron's attempt to sell NEPCO. 81

However, the Examiner has found no evidence to indicate that collections were

accelerated by either NEPCO or Enron. The Examiner's review indicates that any such

acceleration would have been difficult, if not impossible. NEPCO had a finite number of

customers to which it could issue invoices. In addition, for each NEPCO project there

existed an EPC contract with specifically identified milestone payments negotiated in

advance. Thus, an invoice was issued to a customer only when a specific milestone on a

given project was achieved.

81 In the summer of 2001, shortly after Mr. Stanley assumed responsibility for EE&CC (and with it

NEPCO), Emon's senior management determined that NEPCO was not a core business and that it should

be sold. Stanley Interview. Timothy Detmering, then a senior manager of Emon North America Corp.,

was asked to manage the process of selling NEPCO. In the late spring and summer of 2001, Mr.

Detmering assembled a team and began an analysis of how to position NEPCO for sale. As part of Mr.

Detmering's efforts, he retained Arthur Andersen ("Andersen") and Lehman Brothers ("Lehman").

Detmering Depo., at 42, lines 1-4 and at 73, lines 1-9. Andersen was directed to undertake a complete

audit ofNEPCO's books for 1998 thorough 2000 (at that time the last full year of activity). Lehman was

requested to assist in identifying potential purchasers. ld. at 71, lines 23~25. It quickly became apparent to

Mr. Detmering and his team that a saleofNEPCO was going to be difficult. First, Andersen's preliminary

audit revealed that NEPCO's books and records were not in good order and, more significantly, that the

2000 profits generated by the NEPCO business would have to be restated downward because NEPCO had

underestimated remaining completion costs and thus overstated earned income. In addition, Emon realized

that due to timing considerations most ofNEPCO's projects were substantially cash positive (i.e., they had

received more cash at that time than had been paid to vendors and subcontractors) and that in order to sell

NEPCO, Emon would have to effectively put substantial amounts of cash back into NEPCO either as an

adjustment to the sales price or an actual contribution of cash at the sale. "Presentation to Stan Horton,"

Oct. 9, 2001 by R.A. Lydecker, at 5 (stating "Track record complicates any transaction ~ Emon would have

to put back $104 - $163 million in cash") [AB0277 01278-AB0277 01300]. Finally, Emon realized that

the guarantees it had provided to NEPCO's customers were so substantial that few, if any, purchasers could

afford to assume them. Detmering Depo., at 74, lines 14-19. It was unacceptable to Emon to sell NEPCO

without the purchaser's assumption of these guarantees because that would be too risky; Emon would be

guaranteeing work on a project over which it had no control. ld. at 143, lines 13-25 and at 144, lines 1-4.

Accordingly, by late 2001, the effort to sell NEPCO was abandoned. ld. at 73, lines 18-22.

)

-27~

Moreover, in most cases each invoice was reviewed by the customer's

independent engineer to ensure that the claimed milestone was in fact achieved. 82 For

many projects the lender involved in the project also had its own independent engineer

determine whether the milestone was achieved.

Thus, even if NEPCO had issued

invoices improperly in an attempt to accelerate collection of cash from its customers,

those customers would have known that the milestones reflected on the invoice were not

yet achieved and would not have paid on those invoices. Tn addition to the practical

impossibility of attempting to advance collections, there is no indication that any such

acceleration was contemplated, attempted or occurred.

There also is no evidence that NEPCO or Enron made any effort to delay

payments to vendors or subcontractors, or otherwise decrease the NEPCO Entities' use of

CMS funds or that Enron forced or pressured NEPCO to enter into EPC contracts as· a

financing tool for Enron. 83

Net Contribution by NEPCO During 2001

During 2001,84 NEPCO transferred more than $1.720 billion to the CMS. During

the same period, NEPCO received from the CMS more than $1.401 billion in the form of

payments made by the CMS for the benefit of NEPCO. Thus, during the first eleven

months of 2001, NEPCO was a net contributor to the CMS of approximately $319

million.

82

NEPCO's cash receipts for 2001 by month are set forth on the attached

Hattery Interview.

There is no evidence that Euron was encouraging NEPCO to enter into, or that NEPCO was entering

into, EPC contracts merely because they would, initially, generate positive cash flows. To the contrary,

when in the fall of 2001 Euron analyzed the possibility of selling NEPCO, Euron appeared to be surprised

by NEPCO's rapid growth and concerned about whether NEPCO would be able to perform adequately on

all of its contracts. Detrnering Depo., at 22, lines 21-25.

83

84

January 1,2001 through November 30,2001.

-28-

Exhibit 2, and its cash receipts by customer for 2001 are shown on the attached Exhibit 3.

During this same period - January through November 2001 - NEPCO's net intercompany balance with Enron increased by $305 million, from a beginning balance of $83

million to a balance on the eve of the Enron Petition Date of$388 million. This increase

of $305 million in the inter-company receivable due to NEPCO from Enron reflects

NEPCO's $319 million net cash contribution to the CMS, less approximately $14 million

of inter-company assessments for overhead, taxes and similar indirect expenses.

The Examiner has focused upon 2001 because, among other reasons, NEPCO's

inter~company receivable balance increased from $83 million to $388 million. 85

NEPCO's increased positive cash flow in 2001 appears to be the result of

NEPCO's growing business and the timing of the payments NEPCO received under its

EPC contracts. For example, at the end of 2000, NEPCO obtained two large EPC

contracts:

TECOlPanda projects in Gila River, Arizona and El Dorado, Arkansas.

During 2001, when performance under these EPC contracts began, NEPCO received

substantial milestone payments related to these two projects. As of November 2001,

these two new projects alone generated $447 million of receipts, or approximately 25%

ofNEPCO's total receipts for the year.

Affidavit of G. Brian Stanley

In connection with the filing of their bankruptcy petitions, the NEPCO Debtors

submitted the Stanley Affidavit, which identified an amount of cash "swept" from the

NEPCO Debtors by Enron as one of the events causing the NEPCO Debtors to become

In addition, a detailed analysis of years prior to 2001 would not alter the ultimate conclusions expressed

.'

in this Report.

85

-29-

insolvent. 86 Mr. Stanley's affidavit states that as of the Enron Petition Date, Enron had

swept approximately $360 million ofthe NEPCO Debtors' cash.

The Stanley Affidavit was relied upon by certain of the Claimants requesting the

appointment of an examiner. 87 Indeed, certain of the Claimants apparently understood

the Stanley Affidavit to mean that approximately $360 million was swept by Enron

"shortly before" the Enron Petition Date. 88 As discussed in this Report, that belief is

incorrect; cash was swept from NEPCO's account daily over the course ofNEPCO's

almost five year relationship with Enron.

The amount of swept cash identified

explanation.

III

the Stanley Affidavit .also merits

When interviewed, Mr. Stanley stated that a spreadsheet prepared by

NEPCO's Chief Financial Officer, Keith Marlow, was the source for his conclusion that

$360 million had been swept by Enron. 89 The spreadsheet provided by Mr. Stanley in

response to the Examiner's request for the documentary basis for his affidavit does not

reflect $360 million of the NEPCO Cash that was purportedly swept. 90 Mr. Marlow,

when interviewed by representatives of the Examiner, could not identify how Mr. Stanley

had reached the figure of $360 million from the spreadsheet. 91 Mr. Stanley does not

recall specifically how he arrived at the figure set forth in his affidavit. 92

86

Stanley Affidavit ~ 20.

Transcript of Sept. 19,2002 hearing on Goldendale Energy, Inc. 'g Motion to Appoint Examiner, at 103,

lines 7-12.

87

88

[d.

89

Stanley Interview.

90

Spreadsheet entitled "NEPCO Project Cash Analysis as of November 28,2001" [AB0301 00037].

91

Marlow Interview.

92

Stanley Interview.

-30-

E.

Tracing NEPCO's Cash

The cash contributed by NEPCO into the CMS can be traced, using the lowest

intermediate balance rule,93 at least to the Citibank concentration account. Beyond the

Citibank concentration account, however, tracing the funds becomes extremely difficult.

As discussed in Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards), the lowest

intermediate balance rule is a legal fiction used by courts to assist trust beneficiaries who

would otherwise lose the ability to trace trust funds as a result of commingling. The rule

permits courts to presume that when trust funds are commingled with non-trust funds, the

trust funds are used last as the commingled account is drawn down. This preserves, to

the extent possible, the property subject to the trust res for the beneficiary. Thus, the

funds over which NEPCO seeks to assert a constructive trust are presumed to be used last

from the commingled funds in the CMS.

The Examiner concludes that the combination of four accounts in the eMS - the

concentration accounts at Bank of America and Citibank and the related overnight

investment accounts into which both concentration accounts were swept

.~

are the

appropriate "accounts" into which NEPCO could trace its funds because all other CMS

accounts are automatically zero balanced into one of these concentration accounts each

day and the concentration accounts, in turn, are then transferred into the overnight

investment accounts. 94

It is the Examiner's view that in the context of a cash

management system such as the CMS, to the extent that the aggregate balance in these

93

See Appendix A (Applicable Legal Standards).

See discussion below relating to the November 30th Minimal Balance for an exception to this automatic

-'

zero balancing practice.

94

-31-

four accounts remains above the value ofNEPCO's putative res, the lowest intermediate

balance rule is satisfied. 95

Critical Facts

The Examiner's analysis of the tracing issue centers on three critical facts: (i) the

September 1ih Negative Balance; (ii) the Net Consumer Status of NEPCO during the

period from September 12,2001 through the Enron Petition Date; and (iii) the November

30th Minimal Balance.

September 1i

h

Negative Balance. The cash balance in each relevant account in

connection with the September 1ih Negative Balance is set forth in the following chart:96

The Examiner acknowledges that there may be disagreement regarding whether it is appropriate to use

the aggregate amount of cash in the four CMS accounts to determine, at any point in time, if the res has

been extinguished. Using the aggregate balance of these accounts could either assist or hinder NEPCO's

ability to establish a res, depending upon the date in question. As discussed more fully in Appendix A

(Applicable Legal Standards), case law outside of the cash management system context supports the

proposition that a party seeking to impose a constructive trust cannot simply aggregate the amounts in all of

the debtor's separate accounts. See Conn. Gen'l. Life Ins. v. Universal Ins., 838 F.2d 612 (1st Cir. 1988).

The Examiner believes that this reasoning is inapplicable to a cash management system such as the CMS

because the CMS accounts were part of an integrated system that caused the amounts in each account

within the system automatically to be swept into one another on a daily basis. There is case law that

appears to take into consideration the integrated nature of a cash management system when analyzing

constructive trusts. See American Hull Ins. Syndicate v. United States Lines, Inc. (In re United States

Lines, Inc), 79 B.R. 542 (S.D.N.Y. 1987), where the court recognized that funds deposited into overnight

accounts and redeposited at the beginning of the next day would not dissipate the accounts so as to destroy

the res. However, the Examiner is unaware of any published decisions that directly address the aggregation

issue presented by the CMS. Applying a non-aggregation rule in this context could yield strange results.

For example, as depicted in the chart below, the September 12th Negative Balance of $238.2 million

resulted from the Citibank concentration account's $261.8 million negative cash position. On this date,

however, the Bank of America collection account and overnight investment account had positive cash

balances of approximately $2.6 million and $21.0 million, respectively, for a total of approximately $23.6

million. However, there were several dates between September 12, 2001 and the Enron Petition Date when

the Bank of America collection account had a negative cash position (and the related overnight investment

account had a zero balance) but the Citibank collection account had a positive cash balance. Depending

upon the date that is chosen, therefore, in order to preserve the res, NEPCO would have to take the position

that it has the choice between any of the accounts while ignoring the huge negative cash balances in the

other accounts. The Examiner believes this position is inconsistent with the general equitable notions of

tracing in the context ofa constructive trust.

95

96

Accounting Professionals' Analysis [AB0507 01350-AB0507 01355].

-32-

9/12/2001

Enron Corp.

Bank of

America

Concentration

Account

3750494015

$2,651,598

Enron Corp.

Bank of America

Overnight

Investment

Account

$21,020,993

Enron Corp.

Citibank

Concentration

Account

00076486

$(261,839,584)

Enron Corp.

Citibank

Overnight

Investment

Account

$0

Total

$(238,166,993)

The CMS was overdrawn $238 million on September 12, 2001 due to an overdraft of

$262 million in the Citibank concentration account. 97 Accordingly, as of September 12,

2001, the Examiner has concluded that any funds over which NEPCO could assert a

constructive trust were depleted in their entirety and only funds .contributed by NEPCO

subsequent to September 12,2001 could form the basis of a constructive trust res. This

conclusion, coupled with the Net Consumer Status of the NEPCO Entities from

September 12, 2001 through the Enron Petition Date, leads the Examiner to conclude that

(i) NEPCO's ability to trace a trust res is extinguished on September 12,2001 and (ii) no

unjust enrichment occurred after this date.

November 30th Minimal Balance. Assuming arguendo there was still a res in

existence after September 12, 2001, and assuming arguendo that some unjust enrichment

existed, the events occurring on November 29 and 30, 2001, which resulted in the

November 30th Minimal Balance, effectively limit the res to approximately $23 million.

On November 29, 2001, Citibank disabled the daylight overdraft, zero balancing

function of all Enron Citibank accounts linked to the CMS.98 As a result, funds that were

deposited after November 29,2001 directly into the Citibank step accounts were not zero

On September 12, 2001, Emon had approximately $25 million in an investment account at Merrill

Lynch (the "Merrill Investment Account"). The Merrill Investment Account was not part of the CMS, but

was an identifiable asset to which, at least theoretically, NEPCO could attempt to trace funds for its

constructive trust. Even including the Merrill Investment Account, however, Emon was still overdrawn on

September 12, 2001 by approximately $213 million.

97

98

Perkins January 29 Interview; Perkins March 12 Interview.

-33-

balanced into the Citibank concentration account. On November 30, 2001, the Enron

Treasury Department manually transferred funds into certain of the Citibank

disbursement accounts so that the accounts could be used to satisfy that day's obligations.

In addition, the Treasury Department transferred $32.5 million (representing a portion of

certain proceeds received by two Enron subsidiaries under a $1 billion financing related

to Enron's pipeline business) plus an additional $1 million (representing funds from

another Enron subsidiary unrelated to NEPCO) from three non-CMS accounts into four

CMS accounts at Citibank. 99

th

The cash balance of each relevant account in connection with the November 30

Minimal Balance is set forth in the following chart: lOO

11130/2001

Enron Corp.

Bank of

America

Concentration

Account

3750494015

$2,549,423

Enron Corp.

Bank of

America

Overnight

Investment

Account

$0

Enron Corp.

Citibank

Concentration

Account

00076486

$(773,413)

Enron Corp.

Citibank

Overnight

Investment

Account

$1,645,425

All other

EnronCMS

Accounts

$52,897,231

Total

$56,318,666

On November 30, 2001, the available funds in the entire CMS were reduced to

approximately $56.3 million.

However, of this $56.3 million, approximately $33.5

million (i.e., the $32.5 million from the pipeline financing plus the additional $1 million)

consisted of funds in accounts linked to the CMS, but not part of the commingled funds

that could be arguably included in NEPCO's potential res. lOI Accordingly, of the $56.3

million in the CMS on November 30,2001, only $23 million is susceptible of being part

99

100

Accounting Professionals' Analysis [AB0507 01349].

Accounting Professionals' Analysis [AB0507 01350 - AB0507 01355].

101 Since these funds (i) are not funds that came from a source which contained NEPCO commingled funds

and (ii) were deposited into accounts that did not contain, as of November 30, 2001, any NEPCO

commingled funds, the Examiner has concluded that these funds are not subject to an attempt by NEPCO to

)

trace them.

-34-

of any potential res. This potential $23 million res, of course, is available only if the

September 12th Negative Balance and the subsequent Net Consumer Status of NEPCO

are not dispositive.

Ability to Trace Outside the eMS

The Claimants may contend that the NEPCO Debtors should be permitted to

attempt to trace funds that may have been moved by Enron out of the CMS into other

bank accounts not affiliated with the CMS, or to non-cash assets of Enron. There are no

reported decisions directly on point. 102 However, such an effort would be extremely

expensive and very complicated. Of the approximately 1400 bank accounts in which

Enron had an interest prior to its bankruptcy, fewer than 200 were part of the CMS. The

remaining bank accounts .are in some instances accounts held jointly with other entities or

accounts, for example international accounts, unaffiliated with the CMS. 103 As a result,

there may be confidentiality issues, currency translation issues and issues arising under

the laws of foreign jurisdictions which would complicate the audit process.

An audit of each account would be required to determine if any funds from the

CMS, and thus funds to which NEPCO theoretically could trace a res, were moved into

these non-CMS accounts. Not only would each deposit in these accounts need to be

identified, but also once identified each deposit would have to be traced back to its source

to see if it came from an account with CMS funds in it. The Examiner's accountants