Volume 9 Issue 1

Winter 2015

Aspiration Pneumonia

See page 4

Local Regional Anesthesia in the ER

See page 8

Case Study: Lameness in a Greyhound

See page 12

Message from the Chief Executive Officer

Thank You

In the past couple months we released our 2014 Annual Report announcing a 7% increase in

total patients from the previous year to 13,369 and were recognized with several awards and

commendations. We are proud and know that we simply couldn't have accomplished this without

you. We were recognized as one of the Top 10 Most Admired Companies in nonprofit category by

the Portland Business Journal for the eighth year, recognized as one of the Top Animal Non Profits

by the Portland Business Journal, awarded the NW Wild Heritage Award in recognition of our

support for the relationship between wildlife and humans by the Wild Artist Guild, and ranked the

#1 Emergency Veterinary Hospital by Spot Magazine. As an extension of your practice, we share

each of these honors with our referring partners.

CEO Ron Morgan

The reality of our industry consolidating with increasing competition continues to materialize.

We understand you have more options now than ever before for your emergency needs and we are

thankful each time you refer your patients to DoveLewis. Your referrals allow us to maintain a fully staffed, state-of-the-art facility

available to the community 24 hours per day, every single day of the year.

As our annual report illustrated, we put $1,396,735 over the year into our community programs. Our community programs make

us a truly unique organization and include one of the region’s largest volunteer-based animal blood banks, a nationally recognized

pet loss support program, animal-assisted therapy made possible through a partnership with Guide Dogs for the Blind, stabilizing

care for lost, stray, wild and abused animals, education and outreach for veterinary professionals as well as the animal loving

community, and financial assistance for qualifying low-income families facing pet emergencies. It is only with your referral support

and generous donors that we are able to continue and expand these programs.

We are grateful the veterinary community keeps supporting DoveLewis with

referrals and recommendations, because without your continued support our

community may not have access to our many programs. We rely on referring

veterinarians and community supporters to help us keep our doors open. Thank you

for trusting us with your patients’ care during animal emergencies. Your confidence

and support allows us to continue providing our many unique programs to our

community.

Message from the Chief Medical Officer

Think Positive

Lee Herold, DVM,

DACVECC

Chief Medical Officer

Daily affirmations were not invented by the Saturday Night Live character Stuart Smalley; however, this

character played by comedian Al Franken popularized - though undoubtedly also mocked - the idea of

affirmations. Even if you may not know the origin, I’m sure that most people can recite Stuart’s mantra

“I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.” Did this affirmation play a role in

jettisoning this comedian to becoming a two term United States senator? Maybe, though we probably

shouldn’t discount his Harvard education. But in all seriousness I do believe the daily intentions that we

set, whether that is by way of a positive affirmation or a general positive attitude can greatly direct the

course of our day and our life.

I have used affirmation as a tool to set a positive intention for myself at times when I felt very bleak about an obstacle. My first

experience with affirmation was in the summer of 2006. I was daunted by the task of preparing for my critical care specialty board

exams. A trusted advisor, my husband, suggested I use an affirmation. I was skeptical, but what harm could it do? I wrote and

recited an affirmation daily, along with a lot of studying for 3 months in preparation for boards. The great news is that I passed

boards, but when I look back a more important lesson learned that summer was how to create a positive attitude.

Though I will never be an outwardly joyful person, I recognize, admire, and enjoy working with people who are positive and upbeat.

Fortunately veterinary medicine draws an abundance of truly joyful people so I have the pleasure to work with many of them. Not

being a naturally optimistic person, remaining positive is something that I work on daily - it is a goal that is worth the effort it takes.

If you are finding yourself despairing at times, I would suggest emulating the positive people around you, but also maybe letting go

of the mocking stereotype of Stuart Smalley and try reciting a daily positive affirmation.

2 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

DVM Outreach Corner

One of the best parts of my outreach duties is making

personal visits to veterinary clinics. Sometimes I

make unannounced, drop-in visits with tasty treats

and a referral binder because I know you all have

busy schedules. Even when I arrive unannounced I

always find there is a team member who is gracious

enough to give me a tour of the clinic and go through

Ladan Mohammadthe highlights of our information binder. The services

Zadeh, DVM,

I receive the most positive feedback on are the

DACVECC

overnight monitoring package and the shuttle service

– both the routine transport and the critical transport. If you have not utilized

either of these services yet, you may be wondering “are they commonly used?”

Well I have answers for you!

In 2014 we had a total of 279 patients that stayed with DoveLewis under the

overnight monitoring package. 37 of those patients stayed multiple nights

after being with their primary care veterinarian during the day. The overnight

monitoring package was designed to offer continued overnight care for your

stable patients for the affordable price of $220. Common examples of cases

that stay here under the overnight monitoring package include stable renal

failure patients undergoing fluid diuresis, uncomplicated post operative cases,

uncomplicated urinary obstruction cases that have an indwelling urinary

catheter in place, and patients with gastroenteritis. Disqualifications include

the need for EKG monitoring, oxygen therapy, imaging, frequent blood sugar

or blood pressure monitoring, fluid boluses or vasopressor support. The cost

does include replacement IV catheter if needed, fluid therapy, routine injectable

and oral medications, 12 hours of hospitalization and up to two blood panels

performed on our Nova machine which provides electrolytes, BUN, creatinine,

blood glucose, ionized calcium, lactate and PCV/TS. As with other referrals, you

would call to speak to a staff doctor prior to transfer. You might be surprised

which cases can fit into the overnight monitoring package.

The van transport is another service we offer that has increased in popularity

over the last few years. In 2014 we performed 96 routine shuttle transports and

49 critical transports. A routine shuttle is one where a technician assistant only

drives the van to transport a stable patient. One way shuttle cost is $35, round

trip is $55. A great way to take advantage of this service is in combination with

the overnight monitoring. For $275, we can provide round trip shuttle transport

and overnight monitoring. Critical transport utilizes the same van, but a doctor

accompanies the patients. This enables us to provide fluids, monitoring, oxygen

therapy, and even blood transfusions during the transport. The cost of the

critical transport is $225. With both the routine shuttle and critical transport, we

do require the owners contact information and permission prior to performing

the transport. The van services the greater Portland area. You can find the

service area map on our website.

As you can see, the overnight monitoring and shuttle service are well utilized.

But we always have room for more requests. So if you think you have a stable

patient that needs affordable overnight care, or an unstable patient that requires

oxygen during transport, please call us to see our services will fit your needs.

“The overnight monitoring package provided by Dove Lewis has been a

life-saver in more ways than one, for our doctors, clients, and patients

of St. Johns Veterinary Clinic. It removes the worry over maintaining the

recently unblocked cat, the post-op foreign body dog, or the pancreatitis

patient that needs more than 8 hours of IV fluid therapy. What a relief

to know that our patients will be monitored and cared for in such good

fashion, and return to us with updated progress reports. We value this

service greatly, with the peace of mind it has offered over the years.

Thank you, Dove!”

-Mary Blankevoort, DVM

Board of Directors

CEO

Ron Morgan

DoveLewis Emergency Animal Hospital

President

Katherine Wilson, DVM

Forest Heights Veterinary Clinic

Immediate Past President

Adrianne Fairbanks, DVM

Mountain View Veterinary Hospital

Vice President

Governance & Nominating Chair

Carol Opfel, DVM

PDX Visiting Vet LLC

Secretary

Andrew Franklin

member at large

Finance Chair

Sang Ahn, CPA

McDonald Jacobs

PVMA Representative

Lori Gibson, DVM

Compassionate Care Home Pet

Euthanasia Service, P.C.

Medical Advisory Chair

Elizabeth Altermatt Herman, DVM

Murrayhill Veterinary Hospital

Human Resources Chair

Scott Bontempo

Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe

Board Personnel

Courtney Anders, DVM

Pearl Animal Hospital

Julie Poduch

Marketing Consultant

Michael Remsing

Dignified Pet Services

Steven Skinner, DVM, DACVIM

Oregon Vet Specialty Hospital

Kelly Zusman

U.S. Department of Justice

Thomas Mackowiak, DVM

Heartfelt Veterinary Hospital

DoveLewis Emergency Animal

Hospital is recognized as a charitable

organization under Internal Revenue

Code, Section 501(c)(3). All donations

are tax deductible as allowable by law. Federal

Tax ID No. 93–0621534.

St. Johns Veterinary Clinic, Portland OR

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 3

CRITICALIST

Aspiration Pneumonia

Erika Loftin, DVM, DACVECC

Aspiration pneumonia is,

unfortunately, a frequent

occurrence in veterinary patients,

and is recognized far more

commonly in dogs than in cats.

The initial injury (aspiration

pneumonitis) actually occurs

due to chemical irritation from

stomach acid with a high risk for

subsequent bacterial infection

due to altered microenvironment and potentially

aspiration of contaminated liquid and/or pathogenic bacteria in

the oropharynx. While minor aspiration events probably occur

relatively frequently, normal defense mechanisms (coughing,

mucociliary clearance, and the immune system) protect against

the development of clinical pneumonia. When these systems

are impaired or overwhelmed infection occurs. In some cases,

acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) can develop, with a

worsening prognosis and often a need for ventilator support.

should also be evaluated for the cause of the aspiration event,

including megaesophagus, gastrointestinal obstruction or

pancreatitis. Figure 1 shows the typical radiographic findings

of right cranial lung lobe alveolar infiltrate in a patient with

aspiration pneumonia, and Figure 2 shows the same patient 24

hours later. Due to progression of his disease despite aggressive

initial therapy and suspected ARDS, this patient required

mechanical ventilation and 13 days of ICU hospitalization prior

to discharge.

A complete blood count (CBC) and chemistry panel are

recommended in patients with aspiration pneumonia, but

findings are often non-specific. CBC may reveal neutrophilia

with a left shift or less commonly neutropenia. A chemistry

panel is primarily useful for identifying concurrent or underlying

diseases. Additional diagnostic testing should be recommended

as indicated based on the specific patient.

Tracheal wash with cytology and culture is useful to confirm

the diagnosis and identify the organism(s) responsible, which

allows for targeted antibiotic therapy. Samples can be obtained

via bronchoscopy (with bronchoalveolar lavage) or more

commonly via endotracheal or trans-tracheal wash. The use of

a deep oral swab (DOS) as a surrogate for tracheal wash (TW)

to obtain bacterial cultures was recently investigated (Sumner

2011), and the authors concluded that in adult dogs with

aspiration pneumonia, there was partial agreement between

tracheal wash culture and deep oral swab culture, and that DOS

may represent a reasonable alternative sample in patients that

are too unstable for TW. Antibiotic administration can decrease

Factors shown to predispose to aspiration pneumonia in

veterinary patients include gastrointestinal disease, esophageal

disease, neurologic disease, upper airway disease, and recent

anesthesia. Male large-breed dogs appear to be predisposed. A

recent retrospective multicenter study showed a post-anesthetic

aspiration pneumonia incidence of ~0.17%, with significant

association with patients that had a regurgitation

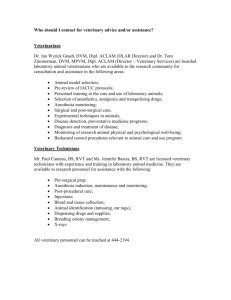

Figure 1a, 1b - Typical ventrodorsal and left lateral radiographic findings of right

episode, and those that received hydromorphone at

cranial lung lobe alveolar infiltrate in a patient with aspiration pneumonia.

induction (Ovbey 2014). The aspiration event is often

unwitnessed and initial clinical signs can be delayed

for hours to days. Physical examination findings

can include fever, weakness, lethargy, increased

respiratory rate and effort, coughing, abnormal lung

sounds on auscultation (including crackles and/or

dull regions), and nasal discharge. Interestingly, in

a recent retrospective study, only about 50% of the

patients presented with signs of aspiration pneumonia

and 26% actually had normal lung sounds on thoracic

auscultation (Tart 2010), so it is important to keep

aspiration pneumonia in mind for patients even without

specific signs of this disease.

The diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia is usually

made on the basis of radiographic findings, most

commonly a dependent alveolar lung pattern. Other

differentials to consider should include infectious

bronchopneumonia, hemorrhage, neoplasia,

atelectasis, and lung lobe torsion. The right middle

lung lobe is the most frequently affected, although

the cranial lung lobes are also commonly implicated.

When aspiration is suspected, it may be helpful to

obtain a left lateral radiograph as this will increase

the ability to detect right-sided infiltrates. It is not

uncommon for radiographic changes to correlate poorly

with the stage and/or severity of disease. Radiographs

4 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

Figure 2a, 2b – Recheck ventrodorsal and right lateral radiographs taken 24 hours

later document significant progression in pulmonary pathology, which necessitated mechanical ventilation. Note the changes are far less obvious on the right

lateral film than on the left lateral film shown in Figure 1.

the yield of bacterial culture, and culture samples should ideally

be obtained prior to initiation of antibiotic therapy.

A variety of bacteria can be found in respiratory cultures, with

Escherichia coli and Pasturella typically the most common.

Other pathogenic respiratory bacteria include Staphylococcus,

Mycoplasma, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, and

Streptococcus species. Polymicrobial cultures are relatively

common, likely due to aspiration of oropharyngeal and/or

enteric bacteria. A recent study (Epstein 2010) demonstrated

that patients with more severe respiratory signs (respiratory

failure requiring ventilator support) had a higher incidence of

antimicrobial resistance on bacterial cultures, suggesting that

these patients should probably be started on more aggressive

antibiotic regimens pending culture results. In this patient

population, 98% of the bacteria cultured were susceptible to

amikacin and 91% were susceptible to imipenem, as compared

to only 35% susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulonate and 48%

susceptible to enrofloxacin. Another recent study (Proulx 2014)

showed that 26% of patients with bacterial pneumonia that had

a respiratory culture performed had at least 1 bacterial isolate

that was resistant to the empirically selected antimicrobials.

The incidence was even higher (57%) in patients that had

received antibiotics over the preceding 4 weeks. This suggests

that airway cultures should be routinely recommended, and that

care should be taken to select different antibiotics in patients

that have recently undergone treatment.

pneumonia. It has been suggested that movement of colloid

molecules across the damaged alveolar endothelium may lead

to increased interstitial fluid accumulation. However, it is also

possible that the more critically ill patients were more likely to

receive colloids and that there is not a causative link.

Respiratory physiotherapy 2-4 times daily is helpful to

mobilize and eliminate respiratory secretions in patients with

pneumonia. In veterinary patients, this is most commonly

provided as nebulization (instillation of very small water droplets

capable of reaching the lower airways) and coupage (rhythmic

clapping against the sides of the thorax to stimulate coughing).

While studies are equivocal on the benefits of this practice, it is

commonly recommended in veterinary patients. No benefit has

been shown to nebulization of antibiotics, and this can cause

airway irritation and inconsistent antibiotic delivery due to poor

lung penetration.

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be started pending bacterial

culture results, or when airway sampling is not feasible due

to patient stability or financial constraints. Cytology can be

evaluated quickly in hospital, and can help guide selection.

In stable patients with mild clinical signs, monotherapy

with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid may be adequate. Patients

that are more clinically compromised should be treated with

combination therapy (such as a potentiated penicillin along

with either a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside). Alternative

antibiotic strategies may be necessary in patients that are

not showing a good clinical response, patients that have been

on recent antibacterial therapy, or based on known hospital

bacterial populations and resistance patterns.

The need for oxygen supplementation is determined by

both subjective and objective means. Pulse oximetry (SpO2)

measurements assess the percentage of hemoglobin saturation

with oxygen and can be obtained non-invasively, but can be

difficult to measure in non-compliant patients, those with

pigmented mucous membranes, and those with arrhythmias.

In general, patients with SpO2 <95% will benefit from

supplementation oxygen. Arterial blood gas measurement is

a more accurate assessment of oxygenation, but is also more

invasive and requires specialized equipment. Subjective

evaluation of the respiratory status of the patient can also be

useful, and includes monitoring respiratory rate and effort,

as well as observing appetite and ability to rest. Oxygen

supplementation can be provided in a variety of ways, including

an oxygen cage, oxygen mask, nasal prongs or tubes, an

oxygen “hood” constructed from a covered E-collar, and via

endotracheal tube. Oxygen supplementation is typically at

~40% initially, but can be provided at higher concentrations

depending on the method and patient requirements. Oxygen

supplementation at high concentrations (60% or above) can

cause toxicity due to free radical accumulation, and use should

ideally be limited to 24 hours or less. Patients with severe

respiratory impairment may require mechanical ventilation.

Some patients with aspiration pneumonia do not require

hospitalization, and can be managed with oral antibiotics.

Radiographs should be monitored serially to help determine

response to therapy, and duration of antibiotic treatment should

ideally continue for 2 weeks past clinical and radiographic

resolution of disease. Many patients are sick enough that they

require hospitalization for supportive care. Fluid therapy should

be used as needed to maintain hydration and perfusion, and

febrile patients in particular can have increased insensible

losses and easily become dehydrated. However, excessive

administration of intravenous fluids should be avoided as

pulmonary capillaries may have increased permeability due to

the acute inflammatory response; this can lead to interstitial

edema and worsening hypoxemia. This risk is higher in

patients with cardiac disease. Patients with sepsis may require

vasopressor support to help maintain perfusion. A recent

retrospective study (Tart 2010) identified colloid therapy as

a negative prognostic indicator in patients with aspiration

Bronchodilators such as terbutaline or theophylline are

sometimes used in patients with aspiration pneumonia, and

can theoretically be useful in ameliorating the bronchospasm

that can accompany chemical injury to the airways. However,

bronchodilators can potentially impede the cough reflex

and also worsen hypoxemia by opening airways that lead to

diseased alveoli and increasing dead-space ventilation. Recent

human ARDS trials have not shown any improvement with

bronchodilator therapy. While glucocorticoids could theoretically

be beneficial to reduce pulmonary inflammation, they are also

immunosuppressive which can be deleterious in the face of

bacterial infection. Glucocorticoids are likely only indicated in

the presence of concurrent inflammatory lung disease, with

upper airway swelling, and with hypoadrenocorticism or other

concurrent steroid-responsive conditions. Cough suppressants

are generally contraindicated in aspiration pneumonia as

they can impair clearance of respiratory secretions. In some

cases, oral or intravenous N-acetylcysteine

Continued on page 6

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 5

Continued from page 5

(mucomyst) may be useful as a mucolytic, but this

medication should not be nebulized due to airway irritation

and bronchospasm. Furosemide should not be used as it can

result in drying and trapping of infectious debris in the lower

airways.

Preventive measures are very important, especially in

patients that have known risk factors for aspiration. Rapid

induction and endotracheal intubation is critical for patients

undergoing general anesthesia, particularly those that

have not been appropriately fasted. Some references have

suggested that increasing gastric pH via administration of

H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors can decrease risk of

airway acid injury in the event of aspiration, while others

have shown increased risk of bacterial pulmonary infection

in human patients that are on these medications. Use of

a prokinetic such as metoclopramide has been shown to

decrease risk of aspiration in humans when given 12 hours

prior as well as on the day of anesthesia. If regurgitation

occurs in an anesthetized patient, care should be taken to

swab or suction the oral cavity, and it may be indicated to

remove the endotracheal tube with the cuff still partially

inflated. These patients should also be monitored very closely

for signs of pneumonia. Patients receiving enteral nutritional

support are also considered at increased risk of aspiration

pneumonia, as well as those with decreased gag reflex,

diseases causing dysphagia, and decreased mentation.

Patients with laryngeal paralysis (with or without arytenoid

lateralization surgery) have an increased risk of aspiration

pneumonia.

With rapid recognition and treatment, the prognosis

for aspiration pneumonia is relatively good. A recent

retrospective study (Tart 2010) showed a survival rate

of approximately 82% in patients treated for aspiration

pneumonia. A statistically significant association was

documented between number of lung lobes affected

radiographically, and survival. No prognostic difference was

found among patients based on signalment, culture results or

specific treatment protocol.

Suggested Reading

RADLAB

Radiology Case Study

Alan Lipman, DVM, DACVR

An 8 year old Springer Spaniel

presented with a 48 hour history

of lethargy and vomiting. Physical

examination determined the patient

had a distended, tense abdomen and

was mildly dehydrated. Abdominal

radiographs were performed and a

lateral view of the abdomen is included

for evaluation. Describe significant

radiographic findings and list possible

differential diagnoses. Please determine what additional

diagnostic imaging may be useful. Continued on page 11

Radiology Services

OUTPATIENT SERVICES & FEES

Radiographs (two views and interpretation; no exam). .......................$235.00

Radiograph Interpretation (per case).................................................$37.00

Interpretation of digital or plain films by Dr. Lipman

Abdominal Ultrasound.......................................................................$330.00

Second Cavity Ultrasound (same patient)........................................$170.00

Dear JD. Bacterial pneumonia in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract.

2014;44(1):143-159.

Echo / Single Organ Ultrasound.......................................................$265.00

Epstein SE, Mellema MS, Hopper K. Airway microbial culture and susceptibility

patterns in dogs and cats with respiratory disease of varying severity. J Vet Emerg Crit

Care 2010;20(6):587-594.

Ultrasound–guided Fluid Drainage*................................................$240.00

Kogan DA, Johnson LR, Sturges BK, Jandrey KE, and Pollard RE. Etiology and clinical

outcome in dogs with aspiration pneumonia: 88 cases (2004-2006). J Am Vet Med

Assoc 2008;233:1748-1755.

Ultrasound–guided FNA*..................................................................$100.00

Ultrasound–guided Fluid Aspirate*................................................. $50.00

Ultrasound–guided Cystocentesis*................................................. $40.00

*All Ultrasound-guided procedure pricing does not include sedation if necessary

CT of Chest, Abdomen, Nasal or Brain............................................$ 879.00

Ovbey DH, Wilson DV, Bednarski RM, Hauptman JG, Stanley BJ, Radlinsky MG,

Larenza MP, Pypendop BH, Rezende ML. Prevalence and risk factors for canine postanesthetic aspiration pneumonia (1999-2009): a multicenter study. Vet Anaesth Analg

2014;41(2):127-136.

(includes contrast, anesthesia & exam fee)

Proulx A, Hume DZ, Drobatz KJ, Reineke EL. In vitro bacterial isolate susceptibility to

empirically selected antimicrobials in 111 dogs with bacterial pneumonia. J Vet Emerg

Crit Care 2014;24(2):194-200.

CT Ortho additional study (same visit). ............................................$ 625.00

CT Lung Met Check (includes anesthesia and exam). .......................$379.00

Sumner CM, Rozanski EA, Sharp CR, Shaw SP. The use of deep oral swabs as a

surrogate for transoral tracheal wash to obtain bacterial cultures in dogs with

pneumonia. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2011;21(5):515-520.

Dr. Alan Lipman, DVM, DACVR Phone: 971.255.5964

Diagnostic Imaging Coordinator:

Katie Olsen, CVT

Phone: 971.255.5964

Tart KM, Babski DM, Lee JA. Potential risks, prognostic indicators, and diagnostic

and treatment modalities affecting survival in dogs with presumptive aspiration

pneumonia: 125 cases (2005-2008). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2010;20(3):319-329.

6 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

CT additional study (same visit).........................................................$325.00

CT Orthopedic (includes contrast, anesthesia & exam fee)................$914.00

Phone consultations are welcomed!

DoveLewis Education

& Outreach Program

Third Thursday Rounds Continuing Education

We invite all doctors and support staff in the

community to attend our free Third Thursday

Rounds. Rounds cover all topics in veterinary

medicine.

For more information on topics and registration

visit dovelewis.org/third-thursday-rounds.

Focused on business.

Passionate about

community.

Pacific Continental Bank

proudly supports DoveLewis

Emergency Animal Hospital.

503-350-1205

therightbank.com

Experience you can

trust to care for your

patients overnight.

TECHNICIAN LECTURES BROUGHT

TO YOU IN PARTNERSHIP WITH

s

“Thank you for alway

zed,

emphasizing organi

ning,

consistent staff trai

development and

skills acquisition.”

d.,

-Liz Hughston, ME

VTS (SAIM, ECC)

RV T, CV T,

Dove overnight monitoring includes exam,

ER or ICU monitoring as determined by

a DoveLewis veterinarian with fluids,

pain management—antibiotics, or oral

medications as prescribed by the referring

veterinarian (if indicated) and patient

status lab work (if necessary).

The medical team at Frontier Veterinary Hospital is so

thankful and appreciative of Dove’s overnight monitoring

package and their shuttle service. We have utilized

both services many times. It is such a relief to be able

to send over our stable post-operative/milder medical

patients and know that we don’t have to worry about

them at home overnight – essentially the overnight

monitoring package is an extension of our hospital’s

continued care... Thank you, Dove!

-Lisa Yung, DVM

main 503.228.7281 • backline 971.255.5990 • fax 503.228.0464

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 7

DVM

Block Party: Local Regional Anesthesia in the ER

Josh Cruz, DVM

If pain control was a party, the opioids,

NSAIDs, and neuromodulating therapies

would be the most glamorous and

gregarious attendees. But sometimes a

very effective member of the party is the

often forgot wallflower, the local regional

block. Local regional anesthesia, or

local blocks, is an essential component

to managing pain in a wide variety

of our patients in the emergency and

critical care setting. Of course, the primary goal of these blocks

is to provide relief from current painful stimuli, or to prevent

the sensation of pain caused by our own intervention. A local

block’s use, however, extends beyond this simple classification.

Allowing for the minimization of other analgesics and sedatives,

ease of administration with minimal risk, and overall cost

effectiveness, make local anesthesia one of the more interesting

and useful characters at this party.

Understanding basic nerve anatomy and physiology is essential

for understanding how local anesthesia works. Rapid changes

to an electrical gradient across nerve membranes allows for

transmission of various signals (pain, sensation, motor) through

nerve fibers. These action potentials of electrical energy are

typically managed by sodium gated channels. Local blocks

utilize these channels to inhibit propagation of nerve signals,

hence, anesthesia. At greater doses of blockade, not only pain

sensation but motor function may be inhibited. While the basic

function is similar among local anesthetics, there are many

local anesthetics that vary in duration and strength of action,

positive/negative side effects, and motor and sensory blockade.

Lidocaine and bupivacaine are the most notable and widely

used sodium channel blockers in the ER/ICU setting, and will

be the focus of this article.

Many local regional anesthesia dose variations and recipes

involving lidocaine/bupivacaine have been described in

8 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

veterinary medicine. Combining both shorter acting lidocaine

with longer acting bupivacaine is often used. Mixing local

blocks with sodium bicarbonate, in an attempt to minimize

patient discomfort and increase onset of anesthesia is still

controversial. Mixing with a vasoconstrictor (epinephrine)

has also been used to prolong duration of analgesia, but may

alter regional pH limiting clinical benefit. Opioids, alpha-2

agonists, and NMDA antagonists (ketamine) have also been

used in conjunction with sodium channel blockade to achieve

regional anesthesia. Ultimately it is difficult to determine the

effectiveness and benefit of adjunctive mixtures to the primary

sodium channel blockage anesthetics. Often in the emergency

setting, keeping it simple is often the best. Patient selection and

reason for anesthesia should help guide your choice but there is

nothing wrong with one drug selection for local blocks.

Various complications exist with performing local blocks.

These complications are usually rare. With appropriate dose,

technique, and patient selection, complications become

insignificant. Systemic absorption and subsequent side

effects to the cardiovascular and central nervous systems

are definitely possible, but using appropriate drug volumes

and understanding species difference should help prevent

this complication. Injection at any site that may already be

compromised from severe trauma or infection should not be

performed. Moving the injection site further up the neurologic

pathway, or increasing the circumference of the block, may be

reasonable options assuming safety of injection and dosage

is still appropriate. Hemorrhage is always a concern, but

understanding landmarks, knowing rough location of major

vessels, and aspirating back prior to injection will help prevent

this complication. Also having a good understanding of patient

systemic health is essential (eg. coagulation parameters,

drug sensitivities, and concurrent medications). Reconsider

performing local anesthesia on patients with coagulopathies

and thrombocytopathies. Nerve trauma is of course possible,

but less likely in the majority of blocks performed in the ER.

Local Block Techniques

The following are four of my favorite, and most commonly used local blocks. This is meant to be a quick guideline, for a more in

depth anatomy and description, other resources should be consulted. The techniques described below are by no means meant to

be all inclusive. Dental, topical, intraarticular, testicular, ring, epidural, and brachial plexus (all-time favorite) blocks are all useful,

but usually used preemptively prior to more advanced surgery or painful stimuli, and not as practical in the ER setting. As with

all blocks, calculating total doses prior to injection, site preparation (clip/scrub), aseptic technique (sterile gloves, needles), and

aspirating prior to injection is essential.

Incisional Line Block

Sacrococcygeal Block

Retrobulbar Block

The most commonly used

block in the ER. One of the

biggest perceived failures of

this block is its failure to work

adequately. Ensuring accurate

dosage and allowing time to

pass (>5 minutes) is essential.

Most traumatic wounds

requiring local regional

anesthesia typically also

require thorough hair clipping,

cleaning, and flushing. Usually

by performing a local block

prior to final wound cleaning,

but well before induced

injury, you are able to give

enough time to allow complete

anesthesia to occur. Also

remember to block those areas

not near the wound site but

near areas of future pain (i.e.

drain placement).

While typically associated with

male feline urinary catheter

placement, any procedure in

which caudal pudendal and tail

anesthesia is required could make

use of this block. This block is only

recently described and further

investigation into its effectiveness

is warranted. However, it has

been used effectively, and for

some cases, allowing urinary

catheterization without use of

general anesthesia. Because

of this, assuming the patient

already has systemic analgesia

and sedation, a sacrococcygeal

block is attempted on the

majority of my patients in which

a urinary catheter needs to be

placed. Depending on block’s

effectiveness, you can either move

on towards catheterization or

general anesthesia if needed.

In the ER setting, the

retrobulbar block is typically

performed prior to enucleation

post traumatic proptosis.

Patient selection is essential in

deciding whether to perform

this block, and controversy still

exists regarding the preferred

technique and overall

effectiveness. Traumatized

anatomy, increased vagal

tone, and unseen bacterial

contamination may lead to

increased procedural risks.

Also due to its location, the

risk for injury and systemic/

CNS absorption is higher.

Regardless, this block can still

be used to good effect and

should be considered.

Intrapleural/

Intercostal Block

An easy, often

underutilized option

for analgesia in critical

patients suffering from

pancreatitis, painful

pleural space disease, or

diaphragmatic disease is

the intrapleural/intercostal

block. Many patients

already on systemic

multimodal analgesia that

still exhibit refractory pain

may see dramatic benefit

from these blocks. For

most of the pain expected

in these patients,

initial administration of

lidocaine, followed by

bupivacaine should be

performed.

Hopefully after reading this, if you are new to local blocks you will be more comfortable performing these various techniques. If

you are already well versed in local blocks, let this be a gentle reminder. I like to think that if it is painful, and I can get close to or

around the nerves responsible for the pain with a needle, local regional anesthesia should be considered. Remember, sometimes

even the wallflower has something to add. After all, everyone is invited to a block party.

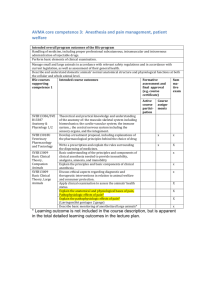

Technique

Dosage

Description

Comments

Incisional Line

Lidocaine 2%

2-4 mg/kg

Bupivacaine 0.5%:

1-2 mg/kg

25 or 22 gauge needle.

Dilute with saline as needed

for volume, or 0.3mls of

sodium bicarbonate per 10

mls.

Sacrococcygeal

Lidocaine 2%: 0.25-0.5 mls

25 gauge needle inserted

30-45 degrees into most

mobile joint caudal to

sacrum.

Sacrococcygeal joint, or

first 2 coccygeal joints are

acceptable. Feel for “pop”.

Retrobulbar

Lidocaine 2%: 1-2mls

22 gauge 1.5 inch needle.

Bent at middle 20 degrees,

inserted at midline or just

lateral to midline under

inferior eyelid.

Aim slightly dorsally and

nasally after initial insertion

about 1-2 cm. Feel for “pop”.

Intrapleural

Lidocaine 2%: 1.5mls/kg,

followed by bupivacaine

0.5%: 1.5mls/kg

Injected at middle of 9th rib

space. 25 to 22 gauge needle

in small patients. 22 gauge

1.5 inch needle for larger

patients.

Block can be instilled into

chest tubes, but will likely

need saline as flush down

tube.

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 9

COMMUNITY

PROGRAM

When to Say ‘Goodbye’

A discussion with Ron Morgan & Enid Traisman, M.S.W., CT

With so many great community programs at DoveLewis, it was hard to choose just

one to write about. But it was my recent experience saying goodbye to our pug,

Lucy, which led me to our Pet Loss Support Program. I asked our Director of the

program, Enid Traisman, certified grief counselor, to help co-write this article.

Lucy Morgan

Ron: I work in a building where end of life for animals is, unfortunately,

sometimes a reality. We see pet parents struggle with the decision to

euthanize their beloved companion animals. Whether their pet has been

battling a disease for years or suffered a recent injury, it is never easy. But

when is it time to say ‘goodbye’? Medically, we can discuss all the statistics,

survival rates, treatment options and pain the pet is experiencing. But the

decision is ultimately in the pet parents’ hands, and what it really comes

down to is the human-animal bond and quality of life. Enid, many of us have

experienced having to make this decision, sometimes more than once - what is

it that makes it so difficult for us to decide when to say ‘goodbye’?

Enid: It is unfortunate that our companion animal life spans are not as long as ours, thus many of us who share that special bond

are faced with very difficult end-of-life issues. Judging whether or not to euthanize a beloved pet can be among life’s most difficult

decisions. When faced with this, people often feel that they have been put unfairly in a God-like position, having to decide between

life and death for someone they love and for whom they are responsible. As compassionate guardians we are also very concerned

about whether our animal is suffering or has lost quality of life.

Ron: With more than a decade as the CEO of an emergency veterinary hospital, I still struggle just as others do when facing my

pet’s life coming to a close. Our dearest Lucy, whom many of you saw in the last issue of VetWrap and on Twitter if you are following

me, had been living with diabetes for almost 5 years. The reality is DoveLewis was able to give us so much more time with her than

we imagined after learning of her diabetes and we are grateful for that. But as a family, we started talking about euthanasia after

many hospital visits and even more so after diabetes took her vision. The dialogue that each person will have with themselves and

their family will likely center around quality of life, as did my own. What guidance can you provide for pet parents having to make

this decision?

Enid: Many people ask me how they will know if it is time to choose euthanasia for their beloved companion animal. The term

“euthanasia” means “the good death,” a death without pain or suffering. To choose this for a pet is both an honor and a burden. I tell

them to first consult with their veterinary professional about prognosis and then to trust their hearts and intuition which is based

on the bond they share and the unspoken communication they have with their pet. I tell them to talk about it with themselves, their

family and friends. And as difficult as it is, it’s important for them to express their feelings, observations and philosophies about

quality of life. Continuing to do this until they come to a decision or identify a “signal’ from their pet letting them know it is time

can be helpful in making this tough decision.

It is important to note that quality of life is interpreted uniquely by each individual. For some folks, any life is life. For others, if their

pet can no longer enjoy his or her normal activities, quality of life has been lost. There is no right or wrong answer; everyone has a

unique perspective.

Ron: When we came to the hard decision in December to let Lucy go run somewhere that she could see again and feel no pain for

the first time in a long time, we knew it was the right thing to do, the selfless thing to do. Just as my family did, there are so many

emotions that people will go through. Tell us about the emotional response and what people can do after you have made this tough

decision to say goodbye.

Enid: In pet loss groups, we often discuss the ‘5 stages of grief’. Specifically, when euthanasia was involved, we often discuss

feelings of guilt, which I describe as anger turned inward. This is a normal part of the grieving process. We do this because in

loving and grieving our pets, we wish we could have done more, or wish we did not have to choose euthanasia. Working toward

forgiving ourselves is essential. Releasing the guilt doesn’t mean that we don’t/didn’t care for our pet; instead it will allow us to

freely tap into all the wonderful memories of a lifetime shared.

But please know that whenever your clients make this tough decision, we are here for them. The Pet Loss Support Program offers

guidance and healing opportunities to those who have said ‘goodbye’ to their beloved pets.

10 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

Reward Theory

{ Education rewards everyone it touches }

CE should reward not only you, but also your patients, clients and practice. So the IDEXX Learning Center provides a

comprehensive curriculum. And learning options that’ll have every member of your team wagging their tail: the veterinarian

who wants to learn from experts face-to-face, techs who love the convenience of online courses, and the practice manager

who’s eager to have protocols communicated consistently across the practice—and with clients.

To turn theory into reality, visit idexxlearningcenter.com.

Knowledge you can put into practice™

IDEXX Learning Center

© 2011 IDEXX Laboratories, Inc. All rights reserved. • 9304-00 • All ®/TM marks are owned by IDEXX Laboratories, Inc. or its affiliates in the United States and/or other countries. The IDEXX Privacy Policy is available at idexx.com.

RADLAB

Radiology Diagnosis Continued from page 6

There is increased soft tissue opacity within the dorsal to mid

abdomen which is displacing the colon ventrally adjacent to

the urinary bladder. There is a loss of serosal margin detail

within the retroperitoneal space with a lack of visualization

of the kidneys and normal retroperitoneal fat. The increased

opacity within this portion of the abdomen has a wispy,

streaking appearance. These findings are consistent with

retroperitoneal effusion. No gross evidence of peritoneal

effusion is identified. Differential diagnoses for retroperitoneal

effusion include retroperitoneal hemorrhage secondary to a

bleeding mass, trauma or coagulopathy, urinary tract leakage,

or less likely a purulent exudate. Abdominal ultrasound may

be useful to evaluate for a neoplastic process involving the

retroperitoneal space (most likely involving kidneys or adrenal

glands). Definitive diagnosis of urinary tract rupture would

require excretory urography or surgical exploratory. Abdominal

ultrasound was performed which demonstrated retroperitoneal

effusion, large bilateral adrenal masses with invasion of the right

adrenal mass into the caudal vena cava (image included) as well

as suspected metastatic nodules involving the cortices of both

kidneys. Differential diagnoses for the adrenal tumors included

adenocarcinoma, pheochromocytoma and hemangiosarcoma

given the large size of the masses and aggressive vascular

invasion of the caudal vena cava.

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 11

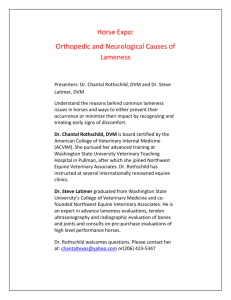

SURGICAL

Lameness in a

Greyhound

Coby Richter, DVM, DACVS

Zoe, a 6 year old female spayed

greyhound presented on

emergency following a witnessed

accident earlier that day. While

exercising at a park, the dog

tripped going down concrete

stairs resulting in laceration and

abrasions to both rear limbs.

She was otherwise in good

health, current on vaccination

and preventive veterinary care, and had no history of lameness.

Zoe is a retired racing dog with an unknown history of injury or

reason for retirement.

At the initial outpatient visit, Zoe’s laceration and abrasions

(over both left and right metatarsals) were treated with standard

wound care and bandaging. The dog was most sensitive to

palpation of the left rear limb but did not show lameness at

a walk or trot in the hospital. She was discharged on oral

antibiotics and pain medications with a plan for a recheck

evaluation with her primary care DVM.

Two weeks following the initial trauma, the owner noticed

a consistent lameness in the left forelimb. Zoe had been on

exercise restriction since the first tripping incident and the

owner was not aware of any trauma that could have resulted

in front limb lameness. At the primary care veterinary clinic, a

lameness exam showed a consistent left front lameness but no

soft tissue swelling or joint effusion. The only pain localization

was upon squeezing the nail of the 4th digit. Radiographs were

taken of the forelimb (Figure 1) with the primary significant

finding being an absence of the distal end of P3 of the 4th

digit. Full bloodwork was collected at that time showing mild

elevation in HCT 64%, lipase 759 (138-755), albumin 4.0 (2.7-3.9),

glucose 118 (63-114), phosphorus 2.4 (2.5-6.1), creatinine 1.6 (0.51.5) and BUN of 19 (9-31).

acute-on-chronic injury to the digit was also possible. Infection

was considered less likely with the total lack of soft tissue

involvement, normal white cell count and normothermia. Injury

at the time of the park stair incident is also possible, potentially

obscured by the more obvious and painful soft tissue trauma

to both rear limbs. Options discussed at that time included

toe amputation, survey radiographs of thorax and longbones,

oncology referral and continued medical management. The

owner elected to try nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication

and continue monitoring. Zoe was started on carprofen (0.9mg/

kg PO BID) and continued exercise restriction.

A recheck evaluation three weeks later showed a left forelimb

lameness of 2-3/5 in the left forelimb with soft tissue swelling

centered at the distal interphalangeal joint (Figure 2). The

owner reported that lameness improved on carprofen, but never

completely resolved. The dog was doing well otherwise. Biopsy

(incisional or needle) was discussed but was not felt to be likely

to produce a diagnosis with less than an excision procedure

(amputation). Furthermore, amputation was considered likely

to be central to the treatment plan regardless of diagnosis.

The owner elected digit amputation at that time. Zoe was

anesthetized in a routine manner and the 4th digit amputated at

the proximal interphalangeal joint. The entire resected segment

was placed in formalin for submission. Zoe was recovered in a

spoon splint to protect the surgical site. She was managed in a

splint for one week, then a simple foot bandage for an additional

two weeks. At the two week recheck and suture removal, Zoe

showed no lameness in the left forelimb. The foot was bandaged

to protect the delicate skin for a final week.

The initial histopathology of the soft tissues indicated mild

reactive fibroplasia with mild mastocytic and neutrophilic

inflammation. Decalcification and histopathology of the digit

followed revealing an expansile mass that arose from the

nailbed epithelium and was compressing the underlying third

phalanx. The final diagnosis was a nailbed keratoacanthoma;

completely excised.

Zoe was started on tramadol and referred to DoveLewis

for surgical consult. The owner reported that there was no

perceptible change in lameness over the four days on tramadol

(3mg/kg PO TID). Upon presentation, Zoe was grade 3/5 lame

in the left forelimb. There was no palpable or visible soft tissue

swelling, joint effusion or crepitus. Full range of motion was

possible in all joints (including digits) without evidence of pain.

Similar to the referring DVM visit of the previous week, the

only pain localization was when the nail of the 4th digit was

squeezed. All toenails were long but otherwise unremarkable.

The abrasions and laceration from the original trauma 2.5 weeks

earlier had healed well.

Subungual (nailbed) neoplasia is relatively common in the dog,

however keratoacanthoma is one of the more rare diagnoses

in this group. Squamous cell carcinomas represent 30-50%

of subungual tumors, followed by malignant melanoma,

osteosarcoma, soft tissue sarcomas and mast cell tumors.

Subungual SCC is locally invasive and has a low metastatic

potential. Regional lymph node or distant metastasis after

excision to the level of P1 has been reported in 10-30% of cases.

Subungual melanomas develop distant metastasis (lymph

nodes, lungs, other systemic sites) in approximately 30-50% of

cases. Prognosis following complete excision of a subungual

melanoma is fair to guarded. Soft tissue sarcomas of the nailbed

are typically locally aggressive. Approximately 75% of nailbed

tumors result in osteolysis that is appreciable on standard foot

radiographs. Other potential causes for local bone lysis would be

infection, trauma and previous surgery.

The differentials at this point included a)neoplasia, b)trauma

and c)infection. Zoe’s age and breed make osteosarcoma one of

the top cancers to consider. However, with her racing history, an

Keratoacanthoma is a benign proliferation that arises from the

superficial epithelium. When a keratoacanthoma forms beneath

the nail, the tumor’s growth is directed instead at the space

12 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

The experience

you trust for

emergencies,

available for

scheduled critical

procedures too!

Consultation & Referral Scheduling Available 24/7, 365

• P

hone consultations

• C

onsultations

• Same-day surgery referrals

(Please speak to a surgeon or staff DVM prior to patient’s arrival.)

main 503.228.7281 • backline 971.255.5990 • fax 503.228.0464

Figure 1

Figure 2

occupied by the third phalanx. Gradual expansion results in pressure necrosis

and resorption of P3 such as that seen in Figure 1. Treatment for solitary tumors is

excision and prognosis is excellent. In Zoe’s case, the toe involved was a weightbearing digit, thus amputation was expected to have a permanent effect upon her

gait. At 3 months post-surgery, the owner reported that Zoe was sound in most of her

activities, although occasionally she would stumble or take one or two lame steps.

DoveLewis would like to thank the Pearl Animal Hospital and Zoe’s owner for

allowing her case to be used for teaching purposes.

Selected References:

Canine digital tumors: a Veterinary Comparative Oncology Group retrospective study of 64 dogs. Henry CJ et al. JVIM

10:720-724, 2005.

Radiographic changes associated with digital, metacarpal and metatarsal tumors and pododermatitis in the dog. Vet

Radiol Ultrasound. 37:327-335, 1996.

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 13

TECHNICIAN

End Tidal C02: Worth the Investment?

Megan Brashear,

BS, CVT, VTS (ECC)

If I were

to take

away all of

your fancy

anesthesia

monitoring

equipment

and you

could

save ONE

monitoring parameter, which would you

choose to keep? Between heart rate/

ECG, ETC02, Sp02, blood pressure (noninvasive but you can choose Doppler

unit or oscillometric), and temperature

which would you choose? Thankfully

many of us have the luxury of using all of

these parameters plus our own eyeballs

and fingers to monitor our anesthetized

patients, but if I were down to just one,

I do not want to monitor anesthesia

without capnometry to measure end tidal

C02.

End tidal C02 is the measurement of

carbon dioxide in each exhaled breath.

Before getting into everything we can

gain by monitoring this value, let’s think

about why it is important to monitor.

Carbon dioxide is the gas that drives

respiration. We (and our patients) inhale

because the respiratory center in our

brain detects higher than normal levels

of carbon dioxide in the blood. We inhale

oxygen, and then exhale that carbon

dioxide every minute of every day of our

lives. If carbon dioxide levels get too high,

our respiratory rate will increase so that

we are exhaling more C02. If levels get

too low, our respiratory rate decreases

so that we hang on to more C02. In our

normal patients without lung disease

or metabolic disease, this process

is sufficient to keep their C02 levels

perfectly normal. When we anesthetize

that patient, the drugs we use can

decrease the ventilatory drive in the brain

and relax the intercostal muscles which

can cause changes in ETC02. Changes

that, because they are anesthetized, the

patient cannot correct on their own.

Do we really need to monitor ETC02?

We can see our patient breathing, we

14 VetWrap Volume 9 Issue 1

have the Sp02 giving us good numbers,

why bother? First of all, our trusty pulse

oximeter is only giving us part of the

picture. With some fancy new models,

we can get some impressive perfusion

information from our pulse oximeter,

but it is still only giving us oxygenation

status of our patient. It is measuring

the percentage of hemoglobin that is

saturated with oxygen. This number

tells us that the patient is receiving

enough oxygen. When that patient is

anesthetized and breathing 100% oxygen,

a low patient Sp02 may be masked by the

increase in inhaled oxygen. And the Sp02

monitor has its limitations – ambient

light, probe placement, movement, and

decreased peripheral perfusion can all

alter the reading. By monitoring ETC02

we are able to determine our patient’s

ventilation status. This is the physical

movement of air in and out of the lungs

and upper respiratory system. By using

both ETC02 and Sp02 we are getting

a more complete picture of our patient

under anesthesia.

Depending on who you read and where

you work, the normal range for ETC02

may differ slightly, but I prefer to use

35mmHg-45mmHg as my ideal range for

an anesthetized patient. Not only are we

monitoring ventilation and respiratory

drive with that normal range, we are

also protecting the patient from acid/

base changes. Elevated levels of carbon

dioxide can lead to acidosis which

can bring additional problems to our

anesthetized patient. By monitoring, we

can intervene to keep the ETC02 within

that normal range.

An elevated ETC02 (>45mmHg), or

hypercapnia, signifies that the patient is

hypoventilating. Common causes for this

include: too deep a plane of anesthesia,

an airway obstruction, pneumothorax,

body position of the patient, and disease

process (remember that obesity is a

disease, especially when we place

those patients in dorsal recumbency).

To correct hypercapnia, increase the

patient’s respiratory rate until the ETC02

reaches a normal level, and adjust

anesthesia as needed. Troubleshooting

the patient may be necessary if a

pneumothorax is present or the patient is

not responding as anticipated.

A decreased ETC02 (<35mmHG) or

hypocapnia, signifies that the patient

is hyperventilating. Common causes

for this include: too light a plane of

anesthesia, pain resulting in tachypnea,

panting, pronounced hypothermia,

decreased cardiac output, or excessive

dead space in the anesthetic circuit. To

correct hypocapnia, pain management

or deeper anesthesia may be required

to allow a lower respiratory rate, as well

as monitoring other vital signs (such as

temperature). Further troubleshooting

may be necessary if the patient is not

responding as anticipated.

In addition to exhaled carbon dioxide, a

capnometer will also display the inhaled

C02 with each breath. This number is

ideally zero, but it is acceptable for a

patient to be rebreathing a small amount

of C02, so a value of 1mmHg or 2mmHg

is tolerable. Higher inhaled C02 numbers

can indicate exhaustion of C02 granules

or a malfunction with the anesthetic

machine or circuit. In very small or

debilitated patients, increased inhaled

C02 numbers may signify a need for

mechanical ventilation or switching to a

non-rebreathing circuit.

Many capnometers will also display

each breath as a waveform, called a

capnograph. Interpreting capnography

is outside the scope of this article, but

can give valuable information about

breathing patterns, the presence of an

airway obstruction, an airway leak, and

breathing over a ventilator.

As mentioned, an end tidal C02 monitor

reads the amount of C02 exhaled with

each breath. Whether a mainstream or

side stream machine, you are looking

at the result of not only ventilation, but

also blood flow, cellular metabolism,

and alveolar ventilation. In order for

C02 to make it out of the lungs and into

your capnometer, your patient must be

perfusing cells and transporting C02

back to the lungs to be exhaled. ETC02

is reliant on ventilation and perfusion. It

is also an instantaneous result, giving

you up to the minute results of what is

happening with your patient. We have

discussed the respiratory monitoring, but

ETC02 numbers are also a clue to the patient’s perfusion and

circulation. Decreased cardiac output can lead to decreased

ETC02. The patient continues to ventilate, exhaling C02, and if

perfusion decreases there is less C02 being brought back to the

lungs to be exhaled. A rapid drop in ETC02 is cause for alarm,

as this can signify impending arrest.

Watching ETC02 in relation to other vital signs under

anesthesia will help you as the anesthetist gain a better overall

understanding of your patient. For instance, you gather the

following vitals on a 5 year old MN Doberman who is undergoing

an elective procedure. He has been under anesthesia for 30

minutes when you record the following:

• Heart rate – 52bpm (ECG normal)

• Respiratory rate – 10bpm (on an anesthesia ventilator)

• Mucous membranes – pink, CRT 1-2 seconds

• SP02 – 99%

• Temperature – 97.6°F

• Blood pressure – 112/78 (MAP 84)

• ETC02 – 33mmHg

This is a young, healthy dog, and looking at his vitals you might

be concerned about his bradycardia, but his blood pressure

looks good, his gums are pink, he is doing fine, right? His ETC02

of 33mmHg is pretty close to normal - does his bradycardia

really need to be addressed? Remember that ETC02 is also

a measurement of metabolism and perfusion. The dog is

hypothermic but not severe, the respiratory rate is not increased,

but this patient may be hypoperfused due to his bradycardia.

After treatment for his bradycardia with glycopyrrolate, this

same patient then had the following vital signs:

• Heart rate – 104bpm

• Respiratory rate – 10bpm

• Mucous membranes – pink, CRT 1-2 seconds

• Sp02 – 99%

• Temperature – 97.6°F

• Blood pressure – 119/81 (MAP 89)

• ETC02 – 41mmHg

By increasing the heart rate we were able to see a slight

increase in blood pressure, but the ETC02 came up to normal.

As we improved perfusion, we improved ETC02.

As mentioned previously, watch ETC02 for sudden changes,

especially dropping. A level that is normal and suddenly

decreases can signal impending arrest. As the animal stops

perfusing, they exhale their C02 and blood flow is too poor to

bring any new C02 to the lungs to be exhaled. That patient is

in danger and needs help immediately. Using that same logic,

monitoring ETC02 on a patient undergoing CPR can let you

know when that patient has a return of spontaneous circulation.

ETC02 readings in a patient that has arrested will be low, into

the low teens or maybe even single digits, but as that animal

begins perfusing their cells again the number will begin to

slowly rise.

Even if you are not convinced enough to say that ETC02 is your

one and only monitoring parameter if you are forced to pick only

one, hopefully you are convinced that monitoring ventilation and

perfusion is a good idea, and worth the investment in an end

tidal C02 monitor for your multi-parameter anesthesia monitor.

A Big Heart

USI works with many Northwest

organizations and we understand

the varied and complex issues

you face in growing your business

and protecting your assets.

We specialize in providing:

·

·

·

·

·

Health & Wellness Benefits

Retirement Plan Services

Commercial Insurance

Risk Management

Private Client Wealth Management

Elizabeth Templeton

Vice President

Employee Benefits

503.417.9231

Elizabeth.Templeton@usi.biz

Volume 9 Issue 1 VetWrap 15

Connect with DoveLewis

<<firstname>> <<lastname>>, <<title>>

<<clinicname>>

<<address>>

<<city>>, <<state>> <<zip>>

Volume 9 Issue 1

Winter 2015

Address changed?

Want to switch to email?

Contact James Gabrio

jgabrio@dovelewis.org or 971.255.5937