NM ELA Assessment Framework Grades 3-8

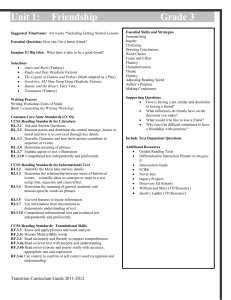

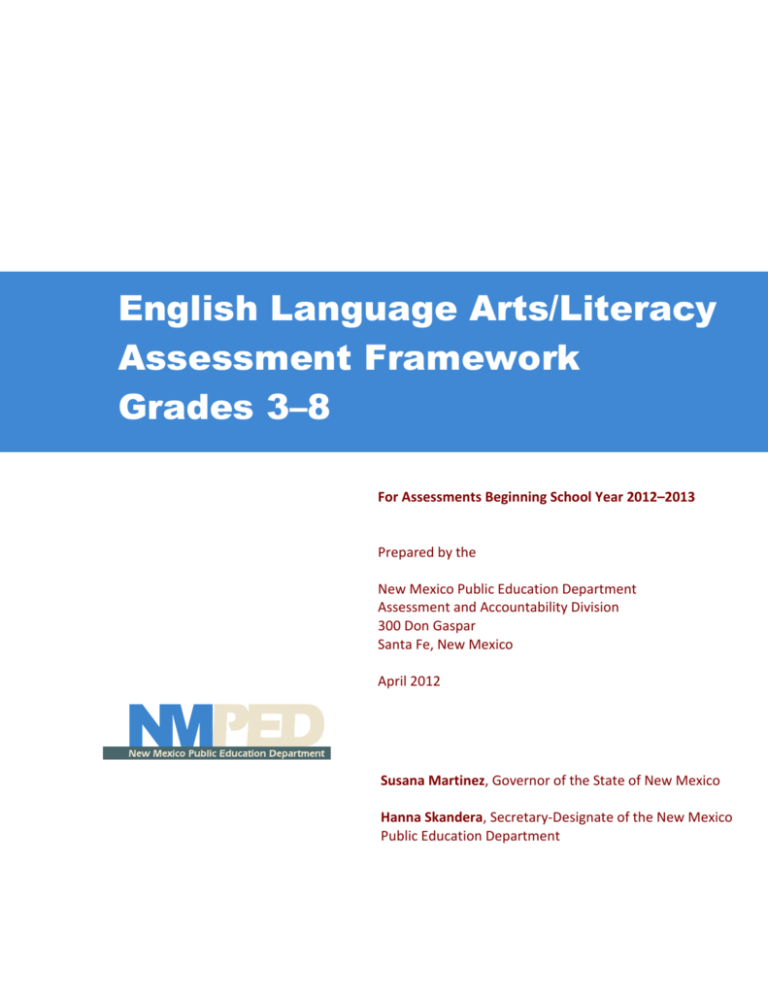

advertisement

English Language Arts/Literacy Assessment Framework Grades 3–8 For Assessments Beginning School Year 2012–2013 Prepared by the New Mexico Public Education Department Assessment and Accountability Division 300 Don Gaspar Santa Fe, New Mexico April 2012 Susana Martinez, Governor of the State of New Mexico Hanna Skandera, Secretary-Designate of the New Mexico Public Education Department Acknowledgements Dr. Pete Goldschmidt is Director of Assessment and Accountability at the New Mexico Public Education Department (PED). Dr. Tom Dauphinee is the division’s Deputy Director. Dr. Dauphinee led the development of the Assessment Frameworks in conjunction with the Assessment Frameworks Development Workgroup and with the assistance at the PED of Claudia Ahlstrom, State Math Specialist; Diana Jaramillo, Education Administrator for the Assessment Bureau; and Melinda Webster, Reading Program Director. Members of the Assessment Frameworks Development Workgroup included: Karon Axtell, Carlsbad Municipal Schools Lorene Beckstead, Los Alamos Public Schools Elizabeth Jacome, Rio Rancho Public Schools JoRaye Jenkins, Carlsbad Municipal Schools Linda Kinane, Albuquerque Public Schools Amanda Knott, Carlsbad Municipal Schools Dora (Mae) Montaño, Rio Rancho Public Schools Linda Pehr, Alamogordo Public Schools Dr. Howard T. Everson, professor of education and psychology at the City University of New York, served as senior technical and policy advisor. New Mexico’s statewide educational foundation, the Advanced Programs Initiative (API), facilitated the project and wrote the report with the support of Marybeth Schubert, Eilani Gerstner, and Melissa Wauneka. The University of New Mexico College of Education and Dean Richard Howell provided invaluable logistical help by hosting the Workgroup at the college on February 27–29, 2012. S u m m a r y E x e c u t i v e New Mexico and 45 other states have adopted Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for public schools, establishing new guidelines for student learning Executive Summary that are internationally competitive. Developed over many years, tested and proven to be effective, these new learning standards draw on research on how students learn and how best to prepare them for college and the increasingly competitive job market. To spur its implementation of CCSS, New Mexico is a member of the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC)—a consortium of 24 states working together to develop a common assessment system. By 2015, all statewide accountability tests in New Mexico will be developed and administered by PARCC. In other words, New Mexico students will be taking the same standardsbased assessments as students in 23 other states. These assessments will be delivered and taken via computer. The New Mexico Public Education Department (PED) is responsible for developing assessment frameworks for statewide testing during the transition to PARCC. The purpose of the English Language Arts/Literacy Assessment Framework is to inform educators, test developers, the public, and policy makers of the topics in the CCSS for reading that will be emphasized over the next two years in New Mexico's Standards Based Assessment (SBA). New Mexico is seeking to better prepare teachers and students to meet the heightened expectations of the new learning standards and the PARCC assessments by steadily raising the rigor of the state’s standards based assessment. In school year 2012–2013, the SBA will test students on the New Mexico state standards for grades 4–8, 10 and 11, and there will be a Bridge Assessment for grade 3 that is dually aligned to CCSS and the New Mexico state standards. In 2013–2014, there will be a “bridge” SBA for students in all tested grades (3–8, 10, and 11) that will look and feel more like the PARCC assessment. The Bridge Assessments will follow the state’s current proficiency ratings—Beginning Step, Nearing Proficiency, Proficient, Advanced—for reporting scores based on New Mexico Academic Content Standards as outlined in the New Mexico Standards Based Assessment: Standard Setting Report (2011). School Grades in the A-F accountability system will continue to be based on growth in student scores using New Mexico Academic Content Standards. The Bridge Assessment will include newly developed items aligned with CCSS starting in 2014, but those items will not count towards school accountability grades. The PED will issue a separate report to districts about student proficiency on CCSS items and tasks. The CCSS value depth of knowledge over breadth of knowledge. This means that New Mexico teachers should expect to teach less content but with more complexity. When designing assignments, teachers should keep in mind the over-arching goals of the ELA CCSS, which include independent comprehension of complex text, the use of evidence to support claims, the acquisition of academic vocabulary, understanding other perspectives and cultures, and the ability to communicate effectively. These goals should be attained through reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 II. About the Common Core State Standards Organization Literacy Practices that affect All Grades Learning Progressions Six “Shifts” in ELA/Literacy College and Career Readiness 2 2 3 3 4 4 III. Design Principles for the Bridge Assessments What is the Bridge Assessment Framework? Design Goals Impact on Instruction: New Priorities for Teachers Use of Technology 5 5 5 6 7 IV. Reporting and Accountability Policy and Definitions Technology Scaffolding Complexity Text Complexity Item Formats Achievement Levels SBA Results and the A-F Accountability System 7 7 7 7 8 8 9 10 10 V. Critical Skills Grades 3–5 Reading: Literature Reading: Informational Text Reading: Foundational Skills Writing Speaking and Listening Language 10 Grades 6–8 Reading: Literature Reading: Informational Text Writing Speaking and Listening Language English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3-8, New Mexico Public Education Department 11 11 11 12 12 12 13 13 13 14 14 i Table of Contents VI. Conclusion 14 VII. Appendices Reference Tables Bibliography 15 ii English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department I. Introduction New Mexico and 45 other states have adopted Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for public schools, establishing new guidelines for student learning that are internationally competitive. The CCSS represent a very different approach to teaching, learning, and assessment—one focusing on fewer but more rigorous standards, and fostering a deeper understanding of critical concepts and the practical applications of knowledge. Developed over many years, tested, and proven to be effective, these new learning standards draw on research on how students learn and how best to prepare them for college and the increasingly competitive job market. The purpose of the English Language Arts/Literacy Assessment Framework is to inform educators, test developers, the public, and policy makers of the topics in the CCSS for reading that will be emphasized over the next two years in New Mexico's Standards Based Assessment (SBA). This “bridge” assessment will be designed to incrementally shift the New Mexico SBA to a closer alignment with the CCSS. To spur its implementation of the CCSS, New Mexico is a member of the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC)—a consortium of 24 states working together to develop a common assessment system for the CCSS. New Mexico is a Governing State, or leader, in the PARCC consortium. The PARCC assessments, which the consortium expects to be available to states in the 2014–2015 school year, will be designed to measure higher-order skills such as critical thinking, reasoning, communications, and problem solving that are essential to college and career readiness. In addition, these next generation assessments will help to determine if students are progressing in their mastery of the content and skills tapped by the CCSS in English language arts and mathematics. They will be designed, as well, to provide parents, educators, and policymakers with comparable performance data on students’ proficiency within and across states. By 2015, all statewide accountability tests in New Mexico will be developed and administered by PARCC. In other words, New Mexico students will be taking the same standards-based assessments as students in 23 other states. These tests will be delivered and taken via computer. New Mexico is seeking to better prepare teachers and students to meet the heightened expectations of the new learning standards and the PARCC assessments by steadily raising the alignment of the State’s standards based assessment to the CCSS. In school year 2012– 2013, for example, the SBA will test students on the New Mexico state standards for grades 4–8, 10, and 11, and there will be a Bridge Assessment for grade 3 that is dually aligned to CCSS and the New Mexico state standards. This means that for third graders the SBA will immediately begin to emphasize the learning goals of CCSS. In 2013–2014, there will be a “bridge” SBA for students in all tested grades (3–8, 10, and 11) that will look and feel more like the PARCC assessment. This means that students will experience test questions more directly aligned to CCSS. By 2014–2015, all students will be taking the PARCC assessments. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 1 The New Mexico Public Education Department (PED) is responsible for developing assessment frameworks for statewide testing during the transition to PARCC. These assessment frameworks define in general terms the knowledge, skills, and abilities to be assessed at each grade and describe the format of the tests and required achievement levels. The assessment frameworks serve another important purpose as well. They signal a shift towards greater transparency about the form of the SBA, emulating the openness about test items and assessment support for teachers that will be implemented with the PARCC system. In CCSS, teachers will become more expert about assessment, its purposes and methodologies, and will be modeling in their own classrooms the examination standards and protocols that are relied on at the state level. II. About the Common Core State Standards According to the expert groups who developed the CCSS for ELA/L, the Standards define what students should understand and be able to do in their study of reading and literacy. Indeed, they set grade-specific standards and benchmarks, but they do not dictate a curriculum or specify teaching methods. This new generation of learning standards emphasizes both content knowledge and conceptual understanding and highlights “capacities” related to problem solving, reasoning and proof, communication, representation, and connections. Organization The CCSS for ELA/L are organized into four strands, or what might be understood as subjects as follows: Reading Writing Speaking and Listening Language In the Reading strand, there are three content areas: Literature Informational Texts Foundational Skills In the CCSS, ELA/L, like mathematics, features a three-tiered structure that describes for each grade the following: The ultimate skillsets that students must acquire—in ELA/L these are the strands The integration of related standards needed to perform complex tasks—in ELA/L an example of such complex task requiring the applications of a cluster or group of standards would be identifying key ideas in a text or recognizing its structure Standards that define what students must understand and be able to do 2 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department Each ELA/L strand has its own so-called “anchor standards” that set expectations that all students must meet if they are to be prepared to enter college and workforce training programs ready to succeed. The anchor standards for each strand are identical across all grades and content areas, emphasizing that they are fundamental to lifelong success. The grade-specific standards correspond to an anchor standard, but progress in complexity and rigor as they move upward in grade level. Literacy Practices that affect all Grades The CCSS describe the characteristics of a student who meets the standards. They call these characteristics Capacities of the Literate Individual. Teachers are to consider the Capacities (or what in the math CCSS are called “practices”) essential skills that must be taught in every course and at every grade and against which students will be assessed. The Capacities of the Literate Individual are to Demonstrate independence; Build strong content knowledge; Respond to the varying demands of audience, task, purpose, and discipline; Comprehend; as well as critique; Value evidence; Use technology and digital media strategically and capably; and, Come to understand other perspectives and cultures. Learning Progressions CCSS were deliberately designed to improve teaching and learning in U.S. public schools by recognizing how student learning progresses. The developers of the CCSS understood that if the newly revised learning standards failed to lead to the alignment of coursework within and across grades they would not promote learning. Learning progressions serve to describe successively, incrementally more sophisticated ways of thinking within an academic domain—showing how topics and concepts follow one another as students learn. They lay out in words and examples what it means to move forward to more expert understanding of a subject, and provide a picture of what it means to “improve” or “grow” in academic proficiency. According to contemporary learning experts, “these pathways or progressions serve to ground curriculum, instruction and assessment” (Heritage, 2008). For this to happen, teachers and students alike need an understanding of how learning develops in knowledge domains like ELA/L. The learning progressions, as articulated in the CCSS, provide guidance about the types of assessment tasks that elicit evidence to support inferences about student achievement at different points along the progression trajectory and vertically across grade levels. The CCSS and the PARCC content frameworks move beyond the traditional horizontal (grade level) definitions of standards to a vertical view of learning in which there is a sequence along which students can move incrementally from novice to more advanced performance. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 3 Thus the CCSS and this assessment framework describe what it means for students to move over time toward a more expert understanding of the big ideas that bring coherence to the academic domain of ELA/L. Six “Shifts” in ELA/Literacy For New Mexico’s students to successfully master the CCSS, it is necessary for teachers to realize the major differences between New Mexico’s current standards and those in the CCSS, and how those differences will be reflected in the SBA. For example, in the elementary grades, the current standards focus heavily on literary text while the CCSS recommend an equal balance between literary and informational text. It is also new that there are literacy standards for social studies, science, and other non-ELA/L courses, requiring all teachers to share responsibility for students’ literacy skills. In all content areas, texts should be more complex and more “authentic” than they are now. Instead of providing students with simpler texts that are easier to understand, the CCSS recommend that teachers provide complex text, but with more time and more scaffolding (see the definition of scaffolding below). The CCSS ask that students demonstrate command of material by providing specific, textbased evidence to support their claims. The CCSS place great importance on students’ ability to use evidence in their writing as well as during classroom discussion. Narrative writing still has a place in the classroom but should not comprise the bulk of students’ writing— even in elementary school. Vocabulary instruction will also look different under the CCSS. Rather than teach esoteric literary terms such as “onomatopoeia” or “assonance,” the CCSS recommend that teachers focus on commonly found, academic terms like “discourse” or “theory” that will allow students to apply these concepts across all content areas. These changes mean that in the CCSS, assessments, including the Bridge Assessments, will include more non-fiction texts, rubrics and prompts, paired passages and academic vocabulary. College and Career Readiness College and career readiness for all students is another seminal idea in the CCSS. The commitment to ensure that all public school students have the knowledge, skills and abilities to be successful in post-secondary education marks a dramatic shift from most states’ prior learning standards—many of which were little more than a disconnected, ‘laundry list’ description of grade-by-grade achievement. Using college and career readiness as a benchmark also brings focus, coherence, and rigor to the CCSS. New Mexico, like the other states adopting the CCSS, has agreed to further align expectations for elementary and secondary school students with college and career 4 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department readiness—requiring all students to take challenging courses in high school that prepare them for college. As a member of PARCC, New Mexico is streamlining its standards based assessment system to hold students, teachers and schools accountable for “clearer, deeper, stronger” learning standards, those that connect solidly with the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in college and at work. In selecting items for the Bridge Assessments, New Mexico will follow this same logic. III. Design Principles for the Bridge Assessments What is the Bridge Assessment Framework? Why is it Needed? An assessment framework, unlike the highly detailed, technical blueprints that states use to develop actual tests, lays out in plain language the design priorities of a standards based assessment so that they can be understood by educational stakeholders and the public at large. New Mexico’s Bridge Assessments for CCSS will be implemented starting in 2013. It is the intent of the Public Education Department to describe the content, knowledge, and skills to be tested across all public schools as New Mexico moves incrementally to implement the CCSS in the next few years. By defining clearly and carefully what it is the Bridge Assessments intend to measure, the Bridge Assessment framework offers a starting place for a public conversation about what will be tested once the CCSS are fully implemented in 2015. The Bridge Assessment frameworks in ELA/L and mathematics will explain to students, their parents, and teachers what we expect students to know and to be able to do as the schools prepare students to be career and college ready. The frameworks will be used to guide school-based instructional design teams as they identify the complimentary sets of knowledge and skills needed for college and career readiness. Design Goals If successful, the 2013 and 2014 bridge standards based assessments in ELA/L will include items that measure the full range of student performance to be measured, including the performances across the spectrum of high and low performing students. Like the current assessments, the Bridge Assessments will provide data to inform instruction, including measures of growth, and outline innovative approaches to assessment design. Also, the assessment frameworks ought to guide the professional development initiatives for ELA/L teachers by identifying clearly the instructional shifts in content knowledge and practices— the demands for rigor, fluency and deep understanding—that are the focus of the CCSS. The assessment frameworks meet these goals by specifying student achievement levels, and by describing the levels of thinking and reasoning that the Bridge Assessment items and (or) tasks demand of the students; how those test items and tasks are distributed proportionately across the content areas tested; and the various item and task formats to English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 5 be used, including multiple-choice and constructed response tasks. These technical details are defined in the next section. The Bridge Assessment frameworks build from the PARCC Model Content Frameworks in ELA/L. In doing so, this assessment framework provides a sufficient level of specification to guide the test development process and serve as a preliminary blueprint for constructing the Bridge Assessment test forms in ELA/L now and in the future. At the same time, the PED has set guidelines for establishing priority areas of assessment, including essential learning standards as described by CCSS/PARCC, those most important to student development, and those not well covered by current New Mexico standards. Finally, the Bridge Assessment framework—though admittedly an interim document—ought to be durable enough to remain relatively stable for the next 3 to 5 years. Impact on Instruction: New Priorities for Teachers After high school graduation, students’ skills are at least as important, if not more so, than the content they know. For that reason, the CCSS tend to focus more on processes rather than just content. Future teaching, learning, and assessment should therefore all become more process-focused. This can be accomplished by infusing more performance tasks and authentic assessments into curricula. At the same time, in CCSS teachers will find that assessments continue to be directly linked to curriculum and instruction—in other words, the material in the standards is both what must be taught and what will be assessed. When designing assignments, teachers should keep in mind the over-arching goals of the ELA/L CCSS, which include independent comprehension of complex text, the use of evidence to support claims, the acquisition of academic vocabulary, understanding other perspectives and cultures, and the ability to communicate effectively. These goals should be attained through reading, writing, speaking, and listening. The CCSS value depth of knowledge over breadth of knowledge. This means that New Mexico teachers should expect to teach less content but with more complexity than they may have in the past. This may include the use of more complex texts, more involved research projects, and higher expectations for students’ use of evidence to support their claims in writing. Another important implication of the CCSS for instruction is the need for teacher collaboration. The learning progressions embedded in the CCSS require that teachers collaborate vertically, to ensure that understanding and fluency build as students move from grade-to-grade. Horizontal collaboration is also extremely important, particularly due to CCSS’s focus on informational text and literacy in all content areas. Finally, experts acknowledge that when implementing new standards, pedagogical changes nearly always lag change in the assessments. New Mexico’s teachers must begin to change instructional techniques and material now, in anticipation of the Bridge Assessments and 6 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department the full transition to CCSS. Although the bridge standards based assessments will not be as much of a change as the PARCC exams, they will reflect the CCSS, requiring students to demonstrate a deeper knowledge of topics. Teachers can therefore anticipate the need for the following: More fidelity to the standards in classroom teaching More professional development to train teachers in the CCSS and inform them of the how the CCSS will be assessed Increased emphasis on collaborative lesson planning within and across grades New strategies for classroom management and use of time in the classroom Use of Technology The Bridge Assessment for third graders in 2013 will be a paper and pencil test. The Bridge Assessments in 2014 and beyond should be developed to be delivered mostly by computer, utilizing formats and technology, like those for short-cycle testing, already available in the districts. IV. Reporting and Accountability Policy and Definitions Technology The PARCC assessments are intended to become computer-based, statewide assessments. There are many benefits to computer-based assessment, including: The ability to make the assessments adaptive increases the opportunity to better test students at the lower and higher ends of achievement. However, the PARCC assessment will not be adaptive. Scoring can be accomplished and reported more quickly than on paper and pencil tests. Standardized scaffolds can be imbedded in the program (see “Scaffolding” below). However, issues of equity would need to be addressed in implementing statewide computer-based assessment including: Disparity among districts that cannot afford enough computers for all students to take the exams Differences in students' experiences using technology because of lack of access Differences in access to broadband internet in different areas of the state (if the assessment is web-based) English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 7 Scaffolding The idea of providing students with “scaffolding”—the additional materials and aids available to students during an assessment—is evolving, and will play a greater role in assessments as technology advances. More often than not, students use “scaffolds” in order to solve more complex problems than they could without such aids. The inclusion of scaffolded assessment items and tasks allows students to demonstrate what they know and can do without placing undo burden on test-taking strategies that emphasize rote memorization or simply recognizing or choosing an answer from a number (multiple) of choices. Examples of these types of assessment items would include those requiring students to solve a multi-part question, applying answers developed at one level to help solve the next part of the question, or to appropriately use a tool, like a Thesaurus, to enhance an answer. With the implementation of the CCSS comes the need to assess more complex topics at a deeper level of conceptual understanding and to tap into students’ higher-order reasoning skills, much of which will require the use of scaffolded assessment items not previously available to students in current testing programs. The shift towards computer-based testing changes the types of scaffolds or supports available to students and allows test designers to imbed standardized scaffolds within the assessment itself. However, before New Mexico transitions toward computer-based assessments, the challenge of providing students with equitable and standardized scaffolds statewide will continue. For example, if certain tools are viewed as legitimate scaffolds and incorporated into the bridge assessments, the question arises whether they should be provided by the PED, the schools, or if students should be required to bring their own. Complexity Increased complexity in standards based assessments is intended to better measure depth of knowledge. Multi-part test items on one problem or passage are intended to provide a rich picture of students' understanding, but to serve that purpose they must be properly constructed. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP): Low-complexity items expect students to recall or recognize concepts or procedures; Moderate-complexity items involve more flexibility of thinking and choice among alternatives than do those in the low-complexity category; and, High-complexity items make heavy demands on students, because they are expected to use reasoning, planning, analysis, judgment, and creative thought. 8 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department Text Complexity One of the goals of the CCSS is to ensure that by the end of high school students can independently read and comprehend the types of texts commonly found in college and the workplace. Currently, there is a large gap between many students’ reading abilities and the demands put forth in increasingly complex fields of study. To close the gap, the CCSS recommend increasing the complexity of text used during instructing, starting in elementary school. Text complexity can be measured in three ways: qualitative, quantitative, and reader/task considerations. Test developers of the bridge standards based assessments should develop test items that meet these thresholds. Qualitative Measures of Text Complexity. There are many characteristics that can make a text complex but that cannot be measured. For example, literary texts with single meanings are less complex than texts, like satires, with multiple levels of meaning. Texts’ structures can also be simplistic—chronological, well-marked, and conventional—or complex, including manipulations of time and sequence. Language is also an important part of a text’s complexity. Texts that rely on literal, clear, contemporary, and conversational language are easier to read than texts with a great deal of figurative, ambiguous, or domainspecific vocabulary. A text also can be made more complex if it requires specific background knowledge, such as cultural or academic content, in order to be fully understood. Quantitative Measures of Text Complexity. Quantitative measures of complexity typically involve the use of a formula to measure a text’s readability. One of the most common formulas, the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Test, uses word and sentence length to approximate complexity. More sophisticated formulas exist, which use things like word frequency and word difficulty to compute a text’s complexity. The use of quantitative measures of complexity are extremely easy to use, but are limited by their inability to “see” things like multiple meanings and figurative language. Reader/Task Considerations. Numerous factors are important when determining whether a particular text is appropriate for a reader. For example, a particular text may be well suited to a reader with specific background knowledge. Or a reader that is very interested in a topic may be more motivated to read a text on that topic. The RAND Reading Study Group identified a reader’s cognitive capabilities, motivation, knowledge, and experiences as important to consider when deciding whether a text is appropriately complex. Item Formats The State’s testing provider, following the guidelines in this document, will develop test items and tasks aligned with CCSS for use in the 2014 Bridge Assessment. Those items will be field tested in the spring of 2013 as part of the SBA, and will be scored but will not be English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 9 counted toward school accountability grades. Field-tested items will be selected for inclusion in the 2014 Bridge Assessment. These items too will be scored but not count toward school accountability grades. The distribution of items on the “bridge” SBAs will remain largely consistent with that used by the SBA over the past two years, with about 80 percent of items being multiple choice, 12 percent short answer, and 8 percent extended response. Constructed response items carry greater weight in the scoring of the SBA, so that multiple choice answers account for about 60 percent of the total score, and constructed response items account for 40 percent. These distribution and scoring percentages represent the state’s targets, and are not meant to be construed as formulas for the Bridge Assessments in 2013 or beyond. Achievement Levels The Bridge Assessments will follow the state’s current proficiency ratings for reporting scores based on New Mexico Academic Content Standards, as outlined in the New Mexico Standards Based Assessment: Standard Setting Report (Measured Progress, 2011): Beginning Step Nearing Proficiency Proficient Advanced In order to preserve the integrity of trend data on student performance, only those items that are aligned with the New Mexico Academic Content Standards and/or dually aligned with the New Mexico Academic Content Standards and the CCSS will be used in calculating student proficiency. SBA Results and the A-F Accountability System School grades in the A-F accountability system will continue to be based on growth in student scores using New Mexico Academic Content Standards. The items and tasks on the bridge standards based assessments that will be scored for accountability purposes will be aligned with current New Mexico state standards. Some of the SBA’s items and tasks also align with CCSS, particularly in Reading, and they will be scored for accountability purposes. This methodology ensures that the performance data the state is using to compute school grades is reliable and valid. The Bridge Assessment will include newly developed items aligned with CCSS starting in 2014. Some of those items will measure essential skills not in New Mexico Academic Content Standards. The PED will issue a separate report to districts about baseline performance on CCSS items and tasks. 10 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department V. Critical Skills In New Mexico and elsewhere, past standards based assessments have measured student proficiency by taking snapshots of student performance on individual grade-level standards. In the Common Core, New Mexico’s assessments are being designed to provide a more complete picture. The Bridge Assessments, modeling the PARCC assessments, follow, and to some extent predict, whether classroom instruction is leading students toward being well prepared for post-secondary education by the time of high school graduation. While all of the CCSS are important and must be taught, we believe that the critical skills identified here should be given priority in instruction and assessment over the next several years. The following high-level description of essential skillsets synthesizes the detailed descriptions of what students must understand and be able to do as found in the 1) strands; 2) the “clustering” of standards described in the anchor standards; and 3) the standards themselves. The skillsets have been identified as critical for one or more of the following reasons: They are fundamental building blocks in college and career readiness They strongly contribute to the Capacities of the Literate Individual and have been identified as critical by the CCSS themselves They are areas not adequately represented in New Mexico’s current standards The most significant shift for ELA/L teachers in grades 3–8 is the central role of Informational Texts in reading—and by extension in writing and language. For that reason, we have provided grade-specific, standard-level detail about Informational Texts in Tables 1 and 2. These tables serve as an exemplar both of the relationship between the standards, the anchor standard groupings and the strand in CCSS, and also to show how learning in the topic grows over time. Table 3 in the Appendix provides a quick reference guide of critical skills, by grade span, described below. Grades 3–5 Reading: Literature When reading literature, students in grades three to five should learn to quote accurately from a text and to identify a text’s theme. They should learn the names of and recognize the structure of different genres of literature. Students should also learn to compare and contrast across an author’s works, across themes and within genres in order to build their knowledge. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 11 Reading: Informational Text The CCSS place a much greater emphasis on students’ ability to comprehend and analyze informational texts than do the New Mexico state standards. This focus on informational text arises from the reality that required reading in college and the workplace is almost entirely informational in nature. CCSS require reading of informational text starting in kindergarten. Students in grades three to five should learn to explain how ideas and relationships develop within an informational text and should be able to interpret the meaning of words based on the way that they are used within a text (connotations, sarcasm, technical meanings, etc.). Reading: Foundational Skills According to the CCSS, foundational reading skills should be taught and assessed through fifth grade. From grades three to five, students should be practicing their phonics and their word analysis skills in order to read and understand texts. As foundational skills only appear in the CCSS through fifth grade, it is important that students are fluent readers with tools to help them independently comprehend complex texts by the time they enter the sixth grade. Writing In the past, narratives comprised a majority of elementary students’ writing. The CCSS include narrative writing, but place a much greater emphasis on writing informational and even argumentative texts than do the current New Mexico standards. This makes sense, as the goal of the CCSS is for students to be college and career ready by the end of high school, after which they will be expected to communicate effectively and write technically. As noted in the Capacities of the Literate Individual, students must be taught to use evidence and details to make their case when writing argumentatively. When writing informationally, students should focus on the effective use of organization. And, when writing narratively, students should work on using writing techniques such as chronology and description to convey real or imagined events. Third to fifth grade students also should learn to conduct research projects that involve gathering appropriate information from varied sources, analyzing the information, and organizing it into a coherent document. Speaking and Listening The speaking and listening requirements of CCSS are not easy to assess with a traditional pencil/paper test. Therefore, the Bridge Assessments will not incorporate these standards. However, effective speaking and listening are required for college and career readiness and should not be neglected as an important part of ELA/L teaching and learning. 12 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department Students in grades three to five should practice speaking and listening by engaging in academic discussions, evaluating various forms of media, and presenting convincing evidence to support a particular point of view. Language Language in the CCSS refers to the use of conventions and to the acquisition of vocabulary. It is widely understood that the depth of a child’s vocabulary is directly correlated with his/her academic performance. It is extremely important that New Mexico’s students broaden their vocabularies as well as improve the tools they possess in order to learn new words in context. Throughout grades three to five, vocabulary acquisition should be a constant focus, and students should practice independently gathering academic vocabulary through reading informational texts as well as using the context of words to determine not only their literal meanings but their implied and/or technical meanings. Grades 6–8 The CCSS for grades six to eight are based largely on the same anchor or “college and career ready” standards as those for grades three to five. The two major differences are that students in grades six to eight are expected to already possess foundational reading skills and that a requirement for reading is literacy in the content areas of history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Reading: Literature Students in grades six to eight, like those in grades three to five, should focus on the use of textual evidence and comparing/contrasting when reading literature. Students in the middle grades are learning to analyze complex texts, not just read and comprehend them. For example, students in the middle grades should be able to use textual evidence to analyze how a theme develops in a text, rather than just be able to quote evidence accurately. Students should be able to compare and contrast types of literature—again, as part of a critical, coherent analysis rather than the simple listing of similarities and differences. In grades six through eight students are growing in demonstrating the abilities or “capacities” of the Literate Individual. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 13 Reading: Informational Texts The CCSS place an even greater emphasis on informational texts in grades six to eight than they do in grades three to five. Fortunately, students in the middle grades gain exposure to these texts in their history, science and even math classes—that way they continue to build their reading skills in addition to gaining the tools to understanding and analyze technical information. When reading informational texts, students in grades six to eight should learn to recognize and interpret the interactions between ideas and relationships that develop over the course of a text. They should not only comprehend complex words, but must understand how word choice shapes textual meaning and an author’s purpose in writing a text. For example, students must be able to determine whether an author addresses conflicting viewpoints. Writing In general, the ELA/L CCSS place a greater emphasis on writing than the current New Mexico standards. In grades six to eight, students should spend a great deal of time writing both expository and argumentative texts, as opposed to narrative texts. Students should become proficient at using clear reasoning and relevant evidence to support their claims in argumentative writing and should use details to sufficiently explain topics in their expository writing. Students should also be able to choose the appropriate structure to convey complex ideas and information effectively. Students in grades six to eight should build on their skills from grades three to five to research topics by gathering and organizing appropriate information. They should expand the number and types of sources they use for information, should analyze those sources, and should be able to juxtapose the information found in those sources with their own point of view. Speaking and Listening Just as in grades three to five, speaking and listening will not be assessed on the grade six to grade eight Bridge Assessments. Speaking and listening are important aspects of teaching and learning in ELA/L, and must not be ignored. Students in grades six to eight should listen carefully to others and engage in discussions that require asking and answering questions based on evidence; analyzing the purpose of and motives behind various forms of media— including whether there is adequate evidence to support a claim; and should present claims and findings in a variety of contexts. 14 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department Language Students’ ability to correctly use conventions and new vocabulary words becomes increasingly important as they move up the grade levels, as shown in Table 4, provided in the Appendix. Students in grades six to eight should study conventions and grammar alongside all other content and skills contained in the CCSS. While some guided learning in these areas is necessary, instructors should keep in mind that students’ independent use of conventions and academic vocabulary is the ultimate goal for college and career readiness. VI. Conclusion The CCSS set out clearly the content knowledge and skills in ELA/L needed to succeed in college and the world of work. The assessment framework presented in this document is intended to set forward-thinking goals for students, their parents and their teachers. If successful, the Bridge Assessment built from this framework will begin to set the stage for New Mexico public education not only beginning in 2013, but beyond and for the next decade. The CCSS and the State’s standards based assessments will raise the bar for all New Mexico’s students. Neither the CCSS nor the Bridge Assessments are intended to dictate curriculum, pedagogy, or the delivery of instruction. The school districts across New Mexico are expected to handle the transition to the CCSS in different ways. This assessment framework is intended to help guide this transition. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 15 VII. Appendices Table 1: Learning Progressions for Reading: Informational Text: Grades 3–5 English/Language Arts Anchor Standards and 3-5 Grade Level Standards for Reading Informational Text Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity Integration of Knowledge and Ideas Craft and Structure Key Ideas and Details Anchor Standards Grades 3-8 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text 16 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers. Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. Determine the main idea of a text; recount the key details and explain how they support the main idea. Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details; summarize the text. Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. Describe the relationship between a series of historical events, scientific ideas or concepts, or steps in technical procedures in a text, using language that pertains to time, sequence, and cause/effect. Explain events, procedures, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text, including what happened and why, based on specific information in the text. Explain the relationships or interactions between two or more individuals, events, ideas, or concepts in a historical, scientific, or technical text based on specific information in the text. Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone. Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole. Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 3 topic or subject area. Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words or phrases in a text relevant to a grade 4 topic or subject area. Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 5 topic or subject area. Use text features and search tools (e.g., key words, sidebars, hyperlinks) to locate information relevant to a given topic efficiently. Describe the overall structure (e.g., chronology, comparison, cause/effect, problem/solution) of events, ideas, concepts, or information in a text or part of a text. Compare and contrast the overall structure (e.g., chronology, comparison, cause/effect, problem/solution) of events, ideas, concepts, or information in two or more texts. Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. Distinguish their own point of view from that of the author of a text. Compare and contrast a firsthand and secondhand account of the same event or topic; describe the differences in focus and the information provided. Analyze multiple accounts of the same event or topic, noting important similarities and differences in the point of view they represent. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. Use information gained from illustrations (e.g., maps, photographs) and the words in a text to demonstrate understanding of the text (e.g., where, when, why, and how key events occur). Interpret information presented visually, orally, or quantitatively (e.g., in charts, graphs, diagrams, time lines, animations, or interactive elements on Web pages) and explain how the information contributes to an understanding of the text in which it appears. Draw on information from multiple print or digital sources, demonstrating the ability to locate an answer to a question quickly or to solve a problem efficiently. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take. Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently. Describe the logical connection between particular sentences and paragraphs in a text (e.g., comparison, cause/effect, first/second/third in a sequence). Explain how an author uses reasons and evidence to support particular points in a text. Explain how an author uses reasons and evidence to support particular points in a text, identifying which reasons and evidence support which point(s). Compare and contrast the most important points and key details presented in two texts on the same topic. Integrate information from two texts on the same topic in order to write or speak about the subject knowledgeably. Integrate information from several texts on the same topic in order to write or speak about the subject knowledgeably. By the end of the year, read and comprehend informational texts, including history/social studies, science, and technical texts, at the high end of the grades 2–3 text complexity band independently and proficiently. By the end of year, read and comprehend informational texts, including history/social studies, science, and technical texts, in the grades 4–5 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range. By the end of the year, read and comprehend informational texts, including history/social studies, science, and technical texts, at the high end of the grades 4–5 text complexity band independently and proficiently. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department Table 2: Learning Progressions for Reading: Informational Text: Grades 6–8 Range of Reading and Level of Text Complexity Integration of Knowledge and Ideas Craft and Structure Key Ideas and Details English/Language Arts Anchor Standards and 6-8 Grade Level Standards for Reading Informational Text Anchor Standards Grades 3-8 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite the textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments. Determine two or more central ideas in a text and analyze their development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text. Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas; provide an objective summary of the text. Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text Analyze in detail how a key individual, event, or idea is introduced, illustrated, and elaborated in a text (e.g., through examples or anecdotes). Analyze the interactions between individuals, events, and ideas in a text (e.g., how ideas influence individuals or events, or how individuals influence ideas or events). Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events (e.g., through comparisons, analogies, or categories). Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the impact of a specific word choice on meaning and tone. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including analogies or allusions to other texts. Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole. Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. Analyze how a particular sentence, paragraph, chapter, or section fits into the overall structure of a text and contributes to the development of the ideas. Analyze the structure an author uses to organize a text, including how the major sections contribute to the whole and to the development of the ideas. Analyze in detail the structure of a specific paragraph in a text, including the role of particular sentences in developing and refining a key concept. Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and explain how it is conveyed in the text. Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author distinguishes his or her position from that of others. Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and analyze how the author acknowledges and responds to conflicting evidence or viewpoints. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words. Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or issue. Compare and contrast a text to an audio, video, or multimedia version of the text, analyzing each medium’s portrayal of the subject (e.g., how the delivery of a speech affects the impact of the words). Evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of using different mediums (e.g., print or digital text, video, multimedia) to present a particular topic or idea. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, distinguishing claims that are supported by reasons and evidence from claims that are not. Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient to support the claims. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; recognize when irrelevant evidence is introduced. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take. Compare and contrast one author’s presentation of events with that of another (e.g., a memoir written by and a biography on the same person). Analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic shape their presentations of key information by emphasizing different evidence or advancing different interpretations of facts. Analyze a case in which two or more texts provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation. Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently. By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6–8 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range. By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction in the grades 6–8 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range. By the end of the year, read and comprehend literary nonfiction at the high end of the grades 6–8 text complexity band independently and proficiently. English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 17 Table 3: Overview of Critical Skills, by Grade Span ELA CCSS Strand Reading: Literature Reading: Informational Text Reading: Foundational Skills Writing Speaking and Listening Knowledge of Language 18 Grades 3–5 Quote accurately from a text, identify themes, learn the names and structures of different genres, learn to compare and contrast within and across texts Explain how ideas and relationships develop within an informational text, interpret the meaning of words based on the way that they are used within a text (connotations, sarcasm, technical meanings, etc.). Practice phonics and their word analysis skills in order to read and understand texts Use evidence and details to make a point, write using organizational techniques such as paragraphs with topic sentences and supporting details, use writing techniques such as chronology and description to convey real or imagined events, conduct research projects that involve gathering appropriate information from varied sources, analyzing the information, and organizing it into a coherent document. Engage in academic discussion; evaluate various forms of media, present convincing evidence to support a particular point of view. Independently gather new vocabulary through reading, use the context of words to determine not only their literal meanings but also their implied and/or technical meanings. Grades 6–8 Analyze texts and provide evidence to support claims, use comparing and contrasting as a tool for analysis. Analyze the interactions between ideas and relationships that develop over the course of a text, analyze how word choice shapes textual meaning, determine an author’s purpose in writing a text and whether that author addresses conflicting viewpoints. Use evidence to support claims in argumentative writing, use details to sufficiently explain topics in expository writing, use a structure that effectively conveys complex ideas and information, expand the number and types of sources they use for information, should analyze those sources, and should be able to juxtapose the information found in those sources with their own point of view Engage in discussions that require asking and answering questions based on evidence, analyze the purpose of and motives behind various forms of media – including whether a speaker presents adequate evidence, present claims and findings in a variety of contexts. Independent use of and acquisition of increasingly complex conventions and academic vocabulary words English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department Table 4: Common Core State Standards Learning Progressions for Language English/Language Arts 3–12 Grade Level Standards for Language English/Language Arts 3-12 Grade Level Standards for Language The following skills, marked with an asterisk (*) in Language standards 1–3, are particularly likely to require continued attention in higher grades as they are applied to increasingly sophisticated writing and speaking. Standard 3 4 5 Grade(s) 6 7 8 9– 10 11– 12 L.3.1f. Ensure subject-verb and pronoun-antecedent agreement. L.3.3a. Choose words and phrases for effect. L.4.1f. Produce complete sentences, recognizing and correcting inappropriate fragments and run-ons. L.4.1g. Correctly use frequently confused words (e.g., to/too/two; there/their). L.4.3a. Choose words and phrases to convey ideas precisely.* L.4.3b. Choose punctuation for effect. L.5.1d. Recognize and correct inappropriate shifts in verb tense. † L.5.2a. Use punctuation to separate items in a series. L.6.1c. Recognize and correct inappropriate shifts in pronoun number and person. L.6.1d. Recognize and correct vague pronouns (i.e., ones with unclear or ambiguous antecedents). L.6.1e. Recognize variations from standard English in their own and others’ writing and speaking, and identify and use strategies to improve expression in conventional language. L.6.2a. Use punctuation (commas, parentheses, dashes) to set off nonrestrictive/parenthetical elements. L.6.3a. Vary sentence patterns for meaning, reader/listener ‡ interest, and style. L.6.3b. Maintain consistency in style and tone. L.7.1c. Place phrases and clauses within a sentence, recognizing and correcting misplaced and dangling modifiers. L.7.3a. Choose language that expresses ideas precisely and concisely, recognizing and eliminating wordiness and redundancy. L.8.1d. Recognize and correct inappropriate shifts in verb voice and mood. L.9–10.1a. Use parallel structure. * Subsumed by L.7.3a † Subsumed by L.9–10.1a ‡ Subsumed by L.11–12.3a English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department 19 Bibliography Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, Technical Subjects, Common Core State Standards Initiative, Council of Chief State Schools Officers and National Governors Association, Washington, DC. Correspondence Between the New Mexico Content Standards and the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts and Mathematics: Summary Report, WestEd, San Francisco, California, December 19, 2011. Illinois Reading Assessment Framework Grades 3-8: State Assessments Beginning Spring 2006, Illinois State Board of Education, Chicago, Illinois, September 2004. New Mexico ELA Assessment Priorities, New Mexico Public Education Department, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2012. Reading Framework for the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress, National Assessment Governing Board, Washington, DC, September 2010. Suggested Outline for Mathematics and English Language Arts Frameworks Grades 6–12, Howard T. Everson, The College Board, New York, New York, (unpublished draft) 20 English Assessment Frameworks, Grades 3–8, New Mexico Public Education Department