Billing Schemes, Part 1: Shell Companies That Don’t Deliver

Page 1 of 4

FRAUD

Billing Schemes, Part 1: Shell Companies That Don’t

Deliver

These scams are among the most costly asset

misappropriations.

BY JOSEPH T. WELLS

JULY 2002

This is the first article in a four-part series on identifying false invoices and their issuers. This and next month’s columns

focus on billing schemes that involve shell companies. Articles in the September and October issues explain how to

detect and prevent two scams that use other, completely different phony-bill strategies.

s he left the county clerk’s office, Stanley, a creative writer at a large advertising firm, gazed at the paper he’d just

obtained and smiled to himself. For $35, it was easily the best investment he had ever made. Stanley pocketed the

document and drove straight to his bank. Less than 30 minutes after presenting the paper to an official, he opened a

business account in the name of SRJ Enterprises—a title that reflected his initials. The simple document—known as a

fictitious-name or DBA (doing business as) certificate—was the key to his grand plan to defraud his employer.

Such documents, available for a modest cost at any county courthouse, allow a person to do business under a

different name. Many small business owners choose to obtain an assumed-name certificate instead of incorporating,

which can cost thousands of dollars. For example, if Bob Black wanted to open Bob’s Body Shop, all he would have to do

is go to the courthouse, fill out a simple form and pay a small fee for a document he could use to open a bank account.

Voila! He’d be in business.

In this study of an actual case, CPAs will learn the first of two ways employees use shell companies to defraud

organizations. Moreover, auditors will learn how to set up effective internal controls to prevent these costly occupational

crimes.

EASY AS 1-2-3

Maybe starting a business was what Stanley had in mind when he established

SJR Enterprises, maybe not. But, fiddling with his wedding ring when he

opened the bank account with a $100 cash deposit, Stanley said his

“business” was located at what was actually the home address of his

girlfriend, Phoebe, a disgruntled colleague from his employer’s accounting

department.

Ways to Cheat an Employer

In billing schemes a company pays

invoices an employee fraudulently

submits to obtain payments he or she is

not entitled to receive. There are four

major types of such ploys, which are by

far the most expensive asset

misappropriations.

On one occasion Stanley had told Phoebe of his latest brainstorm: If he

submitted phony invoices to the company they worked for, she could get them

Shell company schemes use a fake

approved and paid. It didn’t take them long to conclude there was little risk of

entity established by a dishonest

getting caught, especially if they discreetly saved their illicit gains in a local

employee to bill a company for goods or

bank and later used them to start new lives elsewhere.

services it does not receive. The

employee converts the payment to his or

SMOOTH SAILING

her own benefit.

Implementing the scheme was simple. On his home computer Stanley printed

an invoice under the name of SJR Enterprises. Following Phoebe’s

Pass-through schemes use a

instructions, he billed their employer $4,900 for “services performed under

http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2002/Jul/BillingSchemesPart1ShellCompani... 7/17/2012

Billing Schemes, Part 1: Shell Companies That Don’t Deliver

contract 15-822,” a description similar to that found on many other

invoices. Phoebe had chosen that amount because the company rarely

scrutinized invoices for amounts less than $5,000. She then created a “new

vendor” file and phony documents to go with it. Once SJR Enterprises was

recorded in the computer as a vendor, Phoebe simply put the SJR invoice into

a stack of much larger invoices for approval and payment. Right from the

start, their plan worked flawlessly.

Page 2 of 4

shell company established by an

employee to purchase goods or services

for the employer, which are then marked

up and sold to the employer through the

shell. The employee converts the markup to his or her own benefit.

Pay-and-return schemes involve

an employee purposely causing an

overpayment to a legitimate vendor.

When the vendor returns the

overpayment to the company, the

employee embezzles the refund.

Personal-purchase schemes

consist of an employee’s ordering

personal merchandise and charging it to

the company. In some instances, the

crook keeps the merchandise; other

times, he or she returns it for a cash

refund.

In fact, the scheme worked so well Phoebe and Stanley tried it again—and again and again. Ultimately, they bilked the

company out of almost $700,000 in cash over two years. To Stanley and Phoebe, it was a lot of money. But as far as the

company’s total revenues were concerned, it was insignificant. As long as they didn’t get too greedy, Stanley and Phoebe

could have gone on billing their $100 million advertising agency indefinitely. But soon two people would foil Stanley and

Phoebe’s plans—Vivian, Stanley’s wife, and Dennis, the advertising agency’s internal auditor.

Fake Billing: It’s Not Small Change

Source: Occupational Fraud and Abuse, by Joseph T. Wells, Obsidian Publishing Co., Inc., 1997.

SUSPICIONS GROW

Vivian had known for some time Stanley was being unfaithful. He displayed the classic signs: a lack of interest in her, late

“meetings” at the office, vague business trips on the weekend. But Vivian knew there was more. For the last two years,

Stanley had ceded control of their joint checking account to her and no longer asked for spending money.

Vivian considered the possibility that Stanley was stealing from his company. Where else would he get money? If

Stanley was embezzling funds to support a girlfriend, that would be the last straw, Vivian thought. In a fit of anger, she

called Dennis, whom she had met several times at company social functions.

Dennis, who was also a CPA, listened carefully to Vivian’s sketchy evidence and said he would look into it. After her

call, Dennis gave the matter some thought and reasoned that if Stanley was stealing company money, he most likely was

engaged in some sort of fraudulent disbursement scheme. Since Stanley didn’t work with the company’s money himself,

Dennis figured he would need an accomplice who did. And that person would have left a paper trail of phony records. The

http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2002/Jul/BillingSchemesPart1ShellCompani... 7/17/2012

Billing Schemes, Part 1: Shell Companies That Don’t Deliver

Page 3 of 4

challenge would be to find the bogus paperwork among all the company’s legitimate transactions.

CRACKING THE SHELL

Acting on the fraudulent disbursement theory, Dennis took three separate steps to

uncover the billing scheme. First, he examined the company’s line-item costs over a

five-year period, looking for anomalies. This revealed a small uptick in consulting

expenses, which led him to the second step: a detailed examination of vendors.

The billings from SJR Enterprises stood out like a sore thumb. Phoebe had put SJR

on the books as a vendor nearly 24 months earlier. Since that time, its billings had

increased in both frequency and amount. Dennis correctly reasoned that consultants

generally don’t bill more than once a month, nor do they normally quadruple their

billings in one year’s time. He also noted that some SJR invoices weren’t folded and

wondered whether that meant they hadn’t even been mailed. Furthermore, SJR

Enterprises wasn’t in the phone book.

The third and final step in Dennis’s plan was to compare vendor addresses with

employees’ home addresses. Bingo! Dennis knew he had found Stanley’s

accomplice.

Before consulting legal counsel, Dennis went to the courthouse and obtained a

copy of Stanley’s assumed-name certificate—a document of public record. One look

at it removed any doubt that Stanley and SJR Enterprises were one and the same.

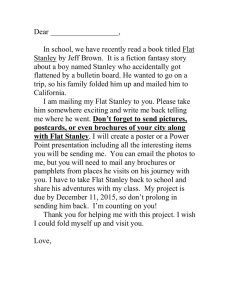

Red Flags

Signs of billing

schemes include

Invoices for

unspecified consulting

or other poorly defined

services.

Unfamiliar vendors.

Vendors that have only a

post-office-box address.

Vendors with company

names consisting only of initials.

Many such companies are

legitimate, but crooks commonly

use this naming convention.

Rapidly increasing

purchases from one vendor.

Vendor billings more than

once a month.

Vendor addresses that

match employee addresses.

Large billings broken into

multiple smaller invoices, each of

which is for an amount that will

not attract attention.

Internal control deficiencies

such as allowing a person who

processes payments to approve

new vendors.

Upon reviewing the evidence, the company’s lawyer didn’t need much convincing. He gave Dennis the go-ahead to

confront Phoebe and Stanley. They both confessed and returned their nest egg—practically all of the $700,000 they’d

stolen. Due to the magnitude of their crime, the pair faced jail time, but—because they were first-time offenders—the

judge sentenced them to probation.

The story doesn’t end there, though: Both Phoebe and Vivian dumped Stanley. And today, menially employed, he

lives in a cramped garage apartment. Alone, he wonders where he went wrong, both morally and strategically.

But Dennis, the internal auditor, knows where he erred and realizes he should’ve seen the connection between the

internal control deficiency that allowed Phoebe to add new vendors and the small increase in consulting expenses. “Soft”

billings—for consulting, advertising and similar services—are ripe targets for this kind of fraud because they typically

describe functions that are difficult to quantify, which makes it harder to assess their validity.

Simple procedures might have prevented this scheme. A credit check on SJR Enterprises would have revealed this

shell company had no history. And looking in the phone book would have shown there was no listing for the bogus

enterprise. Plus, comparing vendor addresses with home addresses of employees before approving new vendors would

have drawn attention to SJR immediately.

http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2002/Jul/BillingSchemesPart1ShellCompani... 7/17/2012

Billing Schemes, Part 1: Shell Companies That Don’t Deliver

Page 4 of 4

In retrospect, Dennis considers himself lucky. Unlike most fraud cases, the company got most of its money back.

Dennis also learned how to prevent future billing schemes. But he feels especially fortunate to still have his job.

JOSEPH T. WELLS, CPA, CFE, is founder and chairman of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in Austin,

Texas, and professor of fraud examination at the University of Texas. Mr. Wells’ article, “ So That’s Why They Call It a

Pyramid Scheme ” ( JofA , Oct.00, page 91), won the Lawler Award for the best article in the JofA in 2000. His e-mail

address is joe@cfenet.com .

Copyright © 2012 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. All rights reserved.

http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/Issues/2002/Jul/BillingSchemesPart1ShellCompani... 7/17/2012