Grade point average: Report of the GPA pilot project 2013-14

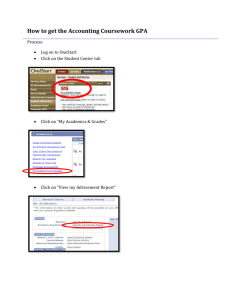

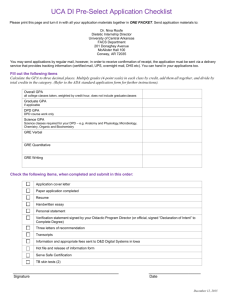

advertisement