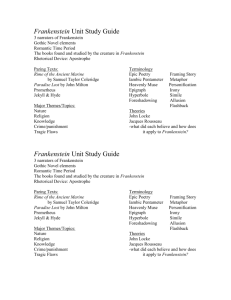

mary shelley, frankenstein

advertisement