Article - UCLA Law Review

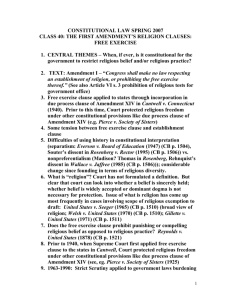

advertisement