Alternative Export-Oriented Industrialization in Africa: Extension from

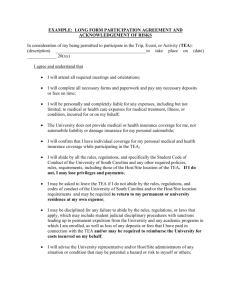

advertisement

Discussion Paper Series Vol.2006-7 Alternative Export-Oriented Industrialization in Africa: Extension from “Spatial Economic Advantage” in the Case of Kenya Yoshi TAKAHASHI, Atsushi OHNO, and Shunji MATSUOKA Graduate School of International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University yoshit@hiroshima-u.ac.jp January 12, 2007 No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form or any means without written permission from author. Abstract: This paper aims at analyzing the capacity development (CD) that is necessary for export-oriented industrialization in Kenya by focusing on selected export industries and investigating the current condition and future direction of industrial development. In East Asian countries, export-oriented industrialization functioned as one of the main vehicles for long-term growth. In more specific terms, there was a consensus that labor-intensive export played a considerable role in facilitating the industrial development processes in those countries. However, as compared to Asia, the exports from Africa have been stagnating. This is mainly because African countries do not enjoy a competitive advantage in terms of labor intensive manufacturing, particularly when compared to Asian exporting countries. However, in recent times, some industries have been increasing their exports due to their “spatial economic advantage” that is based on location characteristics and land abundance. However, further domestic value chain development is required for the sustainability and extension of such industries. East Asian export-oriented industrialization is reviewed at the onset of this paper, and its applicability, particularly to Africa, is questioned. Subsequent to this, we describe the historical export performance and investigate the trade and industrial policy in Kenya. In addition, we analyze the selected industries—i.e., tea and cut flower industries—as prospective cases enjoying spatial economic advantages and the garment industry for African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) as a negative case. Furthermore, the strategy and action plan to be formulated and implemented is examined from the CD perspective. In conclusion, based on the study results, we will propose a research plan for further evaluation of policy recommendations for the Tokyo International Conference on African Development IV (TICAD IV). * This paper was made as the background paper for the Workshop on Industrial Development, Trade and Investment Promotion in Africa: Lessons from Asia at Eighth Annual Global Development Conference of Global Development Network (January 17, 2007, the Beijing Friendship Hotel, Beijing, China) Keywords: Industrialization, Capacity Development, Export Promotion, Competitive Advantage, Africa 1. Introduction: The African competitive advantage In East Asian countries, export-oriented industrialization functioned as one of the main vehicles for long-term growth. More specifically, there exists a consensus among researchers and practitioners that the utilization of low cost advantage, particularly low cost labor, played a considerable role in increasing the exports and facilitating the process of industrial development in these countries. Currently, the economic structure of these countries predominantly comprises more of capital and knowledge-intensive industries. However, this situation is the result of a long process of industrialization that started from labor-intensive import substitution and subsequently moved to labor-intensive export orientation; this shift was accompanied by a relatively enhanced capital- and/or knowledge-intensive import substitution and export orientation, regardless of the different extents of “success” among the countries. As Rodrick (2002) and Lall (2004) claimed, “the East Asian miracle” was accomplished by producing labor-intensive products that were based on cheap but relatively high quality labor as a source of competitive advantage. Lall (2004) also emphasized the role of import substitute industrialization in the early stage of the miracle, as a key policy aimed at future labor-intensive, export-oriented industrialization. In comparison with Asia, the merchandize export—manufactured goods from Africa, in particular—has been stagnant. The principal reason is that African countries do not have an advantage in terms of labor cost, at least in the formal manufacturing sector, particularly when compared with Asian exporting countries such as China and India1. However, in recent times, there have been increasing exports of some natural resource based goods from Kenya, which are exported on the basis of “spatial economic advantages” originating from land abundance and appropriate location in terms of latitude and altitude. In this paper, we focus on this trend and analyze the capacity development (CD) of not only the industries but also other concerned parties such as the government. There have been discussions pertaining to the reason why the manufacturing sector in African countries lacks international competitiveness. Wood and Mayer (2001) pointed out the need to conduct a conventional investigation of not only the relative factor endowment of labor and capital but also that of land and skill. Wood and Mayer’s analysis identified that African countries possess a competitive advantage not in the manufacturing sector generally but in the natural resource based industry with “spatial economic advantage” (including some manufacturing industries such as agro-processing). Furthermore, they asserted that Africa should not refer to the East Asian experience for skill-intensive development; rather, it should draw upon relatively natural resource oriented countries such as Latin America in the mid term. Nevertheless, as the authors admitted, the Latin American achievement is inferior to that of East Asia. Therefore, it is necessary to further discuss the strategy that Africa should adopt after reaching the Latin American level. In contrast, Collier (2000) paid attention to the high transaction costs in Africa that occur due to expensive and unreliable transport, difficult contract enforcement, high information cost, and poor ancillary public services. In addition, he emphasized that since manufacturing is a transactions-intensive activity, it cannot have a competitive advantage. The implication of this argument is that reducing the transaction costs is the responsibility of institutional reform. However, with regard to “spatial economic advantage” based exports, we notice that the gap between exportable natural resource goods and manufacturing goods has been narrowing in recent times. In particular, the horticultural products that are sold at the mega retailers in developed countries are required to meet the social, environmental, and safety standards (Ethical Trade Initiative 2005). Although the relatively lower labor cost in the agricultural sector compensates to some extent, this advantage is expected to shrink in the long run when compared with the manufacturing sector. Moreover, the conditions in Africa are different from those in Asia. Therefore, it is obvious that Africa should pursue a different path to industrialization. In this paper, we propose a plausible option—the strategy to start with natural resource based industries that enjoy “spatial economic advantage”. This strategy is useful for internalizing the value chains of such industries and expanding their impact to a broader base2.There are already successful cases as a result of the implementation of this strategy. 2. Kenyan export performance Over almost a 40-year period, Kenya’s exports experienced some significant structural changes; however, these changes were not very drastic compared to those of the countries that made the transition to “successful” exporters of manufactured goods, such as East Asian countries (Table 1). The most notable negative share change occurred for coffee, tea, and spices. This was due to a decline in the international price of coffee, even though the export of tea has been steadily increasing. The other negative share change occurred in the case of textile fibers made of sisal, which were replaced by synthetics. Two apparently positive changes occurred with respect to mineral fuels and clothing. The increased share for energy products is the result of increased local refinery operations for foreign produced crude petroleum, mainly destined for Uganda and Tanzania. Second, the 10point share increase for clothing is largely due to the adoption of the United States (US) African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) preferences3. In addition, fruits and vegetable (including flowers, hence these items should be regarded as horticulture products as a whole) showed a significant growth in the share of exports4. Table 1 Export by major product groups: comparison between 1964 and 2003 Product Group (SITC) Food and live animals (0) Fruits & vegetables (05) Coffee, tea, & spices (07) Beverages and tobacco (1) Crude materials (2) Textile fibers (26) Crude vegetable materials (29) Mineral fuels and lubricants (3) Petroleum & products (33) Animal & vegetable oils (4) Chemicals (5) Manufactured goods (6) Machinery & transport (7) Misc. manufactures (8) Clothing (84) Other goods (9) All goods (0 to 9) 1964 Exports Value Share ($000) (%) 110,163 6,166 92,323 9 67,626 43,827 9,509 2,948 2,880 82 5,491 4,021 3,667 804 39 1,451 196,261 56.1 3.1 47.0 0.0 34.5 22.3 4.8 1.5 1.5 0.0 2.8 2.0 1.9 0.4 0.0 0.7 100.0 2003 Exports Value Share ($000) (%) 937,326 307,892 486,579 28,559 402,691 18,672 309,978 262,066 260,358 12,334 108,706 172,751 70,046 265,142 209,197 8,345 2,268,595 41.3 13.6 21.4 1.3 17.8 0.8 13.7 11.6 11.5 0.5 4.8 7.6 3.1 11.7 9.2 0.4 100.0 1964-03 Share Change -14.8 10.4 -25.6 1.3 -16.7 -21.5 8.8 10.0 10.0 0.5 2.0 5.6 1.2 11.3 9.2 -0.3 -- Source: Ng and Yeats (2005). In general , the transition of export products over the last 40 years can be regarded as that from agro products to manufacturing products. However, as mentioned below, recent trends appear to indicate steady tea exports and growing horticultural exports. After independence and till the end of the 1970s, Kenya was focusing on the import substitution phase. The policies that sustained it had mixed results. On the positive side, the country enjoyed a considerably high rate of industrial growth by the 1970s, with the manufacturing sector growing at an average rate of 8.0%, as compared with the rates in the 1980s and 1990s, which were below 5%. The general import substitution strategy was also strongly biased against exports. Consequently, the industrial production for export markets substantially slowed down, and hence, manufactured exports comprised only a small proportion of the country’s exports. Between 1984 and 1994, while traditional commodity products such as food and beverages—accounting for over 50% of the total exports—continued to dominate over the period when there were signs of increasing diversification. The share of the food and beverage products in total exports had declined from 68% in 1986 to 52% by 1994, while that of fuels and lubricants had dropped by about two-thirds, from 19% to 7%. Meanwhile, between 1984 and 1994, the shares of industrial supplies and consumer goods categories increased from 15.0% to over 26% and 3.8% to 13.6%, respectively. The European Union (EU) and Africa continue to be the main export destinations for Kenyan exports, both accounting for over 70% of the total exports between 1985 and 1999. Nonetheless, Kenya’s industrial sector remained predominantly inward-looking throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, a number of factors restricted the country’s export growth. First, the government was not only slow in implementing liberalization but also did little to implement effective export promotion policies. Secondly, the government’s institutional and administrative system continued to be biased in favor of import substitution, leading to the slow and uneven implementation of export-promotion. Finally, both the public and private sectors exhibited adverse attitudinal stances that worked against a successful push to increase the export of manufactured goods (Ikiara et al. 2004). Table 2 Recent trends in major exports (Ksh million) Commodity Fish & fish preparations Maize (raw) Meals & flours of wheat Horticulture Sugar confectionery Coffee, unroasted Tea Margarine & shortening Beer made from malt Tobacco & tobacco mfs Hides & skin (undressd) Sisal Stone, sand & gravel Fluorspar Soda ash Metal scrap Pyrethrum extract Petroleum products Animal & vegetable oil Pharmaceuticals Essential oils Insecticides & fungicides Leather Wood mfs Paper & paperboard Textile yarn Cement Iron & steel Metal containers Wire products Footwear Articles of plastics All other commodities Grand Total Source: Central Bureau of Statistics (2004). 1999 2,267 488 423 17,641 874 12,029 33,065 1,309 202 1,554 311 636 166 501 1,280 147 656 9,555 2,186 1,657 3,361 501 387 384 618 303 1,248 2,757 193 181 1,121 1,573 15,831 115,405 2000 2,953 33 201 21,216 1,326 11,707 35,150 246 69 2,167 494 606 123 644 1,440 153 704 9,429 11,204 2,350 2,116 465 486 388 713 488 1,358 2,605 97 113 1,140 2,104 15,476 129,764 2001 3,858 18 155 19,846 1,576 7,460 34,485 245 29 2,887 635 728 85 652 1,993 123 993 12,345 1,298 1,570 2,470 523 576 449 784 518 1,031 3,673 121 117 1,204 2,572 16,415 121,434 2002 4,205 1,693 32 28,334 1,879 6,541 34,376 306 483 3,454 445 792 65 734 2,127 98 798 3,896 2,277 1,697 2,452 353 601 433 647 485 1,479 4,122 144 100 1,549 2,990 22,271 131,858 2003 4,010 125 6 36,485 1,829 6,286 33,005 383 75 2,982 551 906 78 664 2,392 147 813 69 2,410 2,153 2,838 255 1,018 288 777 394 1,976 4,047 204 154 1,457 2,598 25,323 136,698 Table 2 demonstrates the product-wise recent trends in export. As a result of globalization, export-led growth strategies have become a major focus for many countries, including Kenya. Although there have been efforts towards diversification of the export sector, Kenya’s exports are still dominated by primary agricultural products. Tea, horticulture, and coffee continue to be the leading exports, jointly accounting for 52.7% of the total earnings in 2002 as compared with 50.9% in 2001. The export earnings from tea nearly remained at the 2001 levels, while those from coffee decreased by 12.3%. The earnings from horticulture increased by 42% in 2002; however, they declined by 6.5% in 2001. 3. Export promotion and industrial policy Kenya’s industrialization efforts in the post-colonial period have been undertaken through four principal phases of industrial policy—import substitution, export promotion attempt under structural adjustment, and orientation for poverty reduction. This section highlights the main features of each phase. After independence, Kenya pursued an import substitution strategy as a means of promoting industrialization. In order to protect local producers against foreign competition, the government relied on a variety of policy instruments including an overvalued exchange rate, high tariff barriers, import licensing, foreign exchange controls, and quantitative restrictions (Bienen 1990). With regard to the foreign exchange measures, Foreign Exchange Allocation Committee was established to administer foreign exchange quotas for imports; this was implemented to protect domestic producers. The tariffs imposed on imports of final products were generally high as compared to those of capital and intermediate goods. However, due to a weak administrative capacity, quantitative restrictions—import license requirements—proved to be more effective in controlling imports than the imposition of tariffs. After realizing the limitations of the import substitution phase toward the end of the 1970s, Kenya attempted the export promotion phase. Some of these intentions were evident from the development plans and policy documents published during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Fourth Development Plan (1979–1984) clarified the recommended measures: the replacement of quantitative restrictions with equivalent tariffs, the reduction of tariff rates, a more liberal exchange rate policy, and the strengthening of export promotion schemes. However, the export promotion measures implemented were not very substantial. This poor implementation record of policy measures was partly attributed to the policy constraints that the policy-makers encountered (Bienen 1990). After the initial round of liberalization, the government temporarily reversed the reform process and reintroduced import controls for certain items (Swamy 1994). A number of institutional and market oriented initiatives were taken between 1985–90, such as the export compensation, the Manufacturing Under Bond (MUB), and import duty and Value Added Tax (VAT) remission schemes. However, even after the publication of the 1986 Sessional Paper No. 1, which clearly mentioned the transition from import substitution to export promotion the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Program (SAP), these measures met with limited success. Somewhat similar problems also emerged in other African countries. In general, the governments of these African countries failed to implement across-the-board import liberalization. Regardless of the intended results, these reforms weakened the industrial base of their economies and reduced the overall productive dynamism. Moreover, they squeezed the import-competing sectors without sufficiently stimulating new, non-traditional export sectors5. The early 1990s marked the beginning of sweeping economic and political reforms that aimed to achieve an effective transition from a highly protected domestic market to a more competitive environment. However, in general, the liberalization policies that started in 1980 had a number of drawbacks in terms of speed and enforcement, which resulted from a lack of ownership. This period witnessed the implementation of numerous measures such as foreign exchange liberalization, further reduction in import duties, restructuring of VAT, introduction of an Essential Goods Production Support Programme, and increased incentives for the Export Processing Zone (EPZ) enterprises. In spite of these measures, the manufacturing sector continued to be highly protected. In the 1990s, the government established organizations such as Export Promotion Zone Agency, Export Promotion Council (EPC), and Kenya Investment Agency for export promotion, including the inducement of foreign direct investment. Nevertheless, the implementation of the activities planned by these organizations was difficult not only due to the recession that was caused by the stoppage of loans from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank but also because of the retrenchment of the government budget. Following this, the World Bank changed its main policy from SAP to Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS). As in the Kenyan version of PRS, the Economic Recovery Strategy for Wealth and Employment Creation 2003–2007 (ERS) made a mention of “volume growth of exports of 5.7% annually as well as diversification,” and trade capacity development was officially recognized for further export growth and diversification. As a result, the Ministry of Trade and Industry has undertaken several efforts including the formulation of the Export Strategic Plan. Consequently, poverty reduction became one of the main objectives in the process of industrial development, particularly export promotion. For instance, in the case of horticulture products, not only export growth itself but also the ratio of smallholders for export production or labor conditions, such as wages, came to be taken into consideration. Western donors like the Department for International Development of United Kingdom are more concerned about these matters. In the short run, export promotion and poverty reduction might be traded off with requests from mega retailers in developed countries regarding an increased estate-type production for securing safety conditions in their market. Moreover, in the long run, direct measures for poverty reduction might also weaken the international competitiveness. Kenya, like other exporting countries in the developing world, is at the point of cautiously balancing and pursuing two objectives at the same time. 4. Case studies of the selected industries This section identifies the current conditions and future prospects of competitive advantages and value chain expansions in the selected industries from the viewpoint of the factors for success and the role of the government. The cases are of relatively successful industries, namely, the tea, cut flower, and garment industries located in EPZs. In more specific terms, this section discuses the production and export performance, international competition conditions, product and market characteristics, Kenyan competitive advantages, and value chain expansion. As regards value chains in particular, it should be noted that the different aspects are emphasized and compared with the emerging discussion on this matter in the aid community, which focuses on labor input, production, logistics, and marketing, with particular emphasis on the direct contribution to poverty reduction through the improvement of labor conditions6. Here, we include inputs other than labor, that is, intermediate goods, capital goods, and research and development, which are equally important for further industrial development. 4.1 Tea industry Tea is Kenya’s largest exported commodity item; it comprises 21.8% of the total export (Central Bureau of Statistics 2006). Approximately 95% of the locally produced tea is exported—mostly in bulk, while only a small percentage is packaged for export. In 2003, over 300,000 tons of tea was exported and earning reached approximately Kshs 41 billion (Figure 1). The major tea export destinations were Pakistan (23.7%), Egypt (18.5%), United Kingdom (15.5%), and Afghanistan (13.7%). Kenya is the fourth largest tea producer and the second largest exporter in the world. The country contributes 10% of the total global tea production and commands 21% of all global tea exports. In 2003, the total hectarage under tea cultivation was approximately 131,418, with a production of 293,670 tonnes. The smallholder tea covered about 86,338 ha, with a production of 180,789 tonnes. Table 4 provides the trend in tea hectarage and the production of tea from 1999 to 2003. Over the five year duration, both hectarage and production have increased. Currently, approximately 62% of the country’s total crop is produced by the smallholder growers who process and market their crop through their own management agency, Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA) Ltd., which is the largest single tea producer in the world. The balance of 38% is produced by the large scale estates, which are managed by major multinational firms that are associated with tea. Figure 1 Kenyan tea exports volume and value (Volume in metric tons, value in thousand US$) 600,000 499,037 500,000 465,442 437,914 435,746 439,686 400,000 300,000 271,739 270,151 275,225 269,962 216,990 200,000 100,000 0 1999 2000 2001 Volume Source: Export Processing Zone Authority (2005). 2002 Value 2003 Table 3 Production, Area, and Average Yield of Tea by Type of Grower, 2001–2005 2001 AREA (Ha) '000 Smallholder* Estates TOTAL PRODUCTION (Tonnes) '000 Smallholder* Estates TOTAL AVERAGE YIELD (Kg/Ha)** Smallholder Estates Source: Tea Board of Kenya ** Obtained by dividing current production by the area four years ago * Provisional 2002 2003 2004 2005* 85.5 38.8 124.3 85.9 44.4 130.3 86.4 45.1 131.5 88.0 48.8 136.7 92.7 48.6 141.3 181.7 112.9 294.6 175.9 111.2 287.1 180.8 112.9 293.7 192.6 132.1 324.6 197.7 130.8 328.5 2,147.0 3,453.0 2,078.0 3,294.0 2,136.0 3,331.0 2,263.0 3,739.0 2,312.0 3,372.0 Source: Central Bureau of Statistics (2006). Small-scale tea growers who are estimated to be 400,000 in number, process and market their tea through 53 tea factories under KTDA, while large-scale tea growers (tea estates) process and market their tea through 39 tea factories that are operated on an individual, private basis 7 . KTDA is overseeing almost 15,000 employees and liaising with over one-quarter million tea growers nationwide. In addition to processing and marketing smallholder tea, the KTDA also offers a number of services to farmers, such as fertiliser supply and extension, on the payment of a fee. Fertilizer is offered to tea producers on credit; its payment is recovered after the tea is sold. East African tea is superior to Asian tea in some aspects. In particular, Kenyan tea does not have to contend with pests because it is cultivated at high altitudes; therefore, it boasts of almost 100 years of pesticide-free cultivation. A year-round production results in stable quality and delivery, due to which, the land productivity of tea production is 1,938 kg/ha—much higher than the world average of 1,222 kg (FAO 2000). In recent times, other characteristics of Kenyan tea have also been appreciated; these include: (1) high levels of catechin, (2) high levels of polyphenol, and (3) the tea leaves, which are picked by hand, are clean because they do not come into contact with the ground (JETRO 2005)8. Another advantage of the tea industry is its domestic deployment of the value chain. In this context, we have categorized the elements of a value chain into five aspects: production, research and development, capital goods, intermediate goods, and marketing (branding). In terms of research and development, research on improvement in the breeding and cultivation method is conducted domestically by the Tea Research Foundation of Kenya under Tea Board of Kenya. Its mandatory is to carry out research on tea and advise growers on the control of pests and diseases, improvement of planting material, general husbandry, yields, and quality. Thus far, the foundation has developed and released over 45 well-adapted tea clones to growers. Universities and individual firms also contributed to this research. It was crucial to develop clones that were not only high yielding but also resistant to drought, pests, and diseases. The foundation also aims at producing germplasm targeted for specific agrozones. In order to do so, the foundation has embraced the use of new tools for breeding, which include tissue culture and biotechnology. In addition to researching crop volume and teas that are resistant to pests, the foundation has purportedly discovered high catechin, extremely low caffeine teas. The main source of seeds and seedlings is the commodity marketing body, KTDA. The availability and the quality of the planting materials are hampered by the lack of commercialization of seed and seedlings and their multiplication and distribution by the commodity bodies. In this respect, it is necessary that the domestic production of seeds and seedlings should be more evaluated. Certain capital goods such as machines and equipment used in the roasting process are domestically produced, while packaging machines are imported, mainly from Europe. Nairobi is the main location for the manufacturers of tea (and coffee) machinery. (Matthews 1987). However, according to a large manufacturer of tea processing equipment, the basic design of tea machinery has not undergone a major, successful innovation. A standard mechanical process—still in demand today—had been in operation since the late nineteenth century. These examples reflect the lack of product-innovation in Kenya’s machinery producing sector (Matthews 1991). In comparison to India, where a considerable number of tea processing machinery firms are producing and exporting their products, the situation in Kenya leaves much to be improved. Intermediate goods—not only tea leaves but also packaging materials—are produced in Kenya. Fertilizers are purchased in bulk, mostly from international suppliers9. A large proportion of the Kenyan imports come from Romania, Ukraine, the United States, Europe, Middle East, and South Africa. Tea fertilizers, mainly NPK (nitrogen, phosphoric acid, and kalium) fertilizer, account for 21% of the national consumption. Tea fertilizer imports have risen by 85% from the previous period. (Ariga et al., 2006). According to the Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Industry (1999), there are only two factories for fertilizer production in Kenya. The first one is based at Thika, which manufactures single superphosphate (10,000 tons per annum), and the other is based in Nakuru, which imports manufactured fertilizers and blends them according to various NPK grades (40,000 tons per annum). With regard to marketing (branding), Kenya tea has been traditionally sold in the market in a bulk form and is much sought after by leading tea companies for blending and adding taste to the most respected tea brands in the world. Over the last few years, Kenya has increased the volume of value added tea sales from under 5% of total sales to approximately 12%. Till date, all the tea exported to Sudan is packaged under company brand names. The biggest brand in the domestic market, Kenya Tea Packers (KETEPA), is exporting products to the countries in the Middle East. Although the current export ratio is 5%, KETEPA plans to increase it to 20% in the next five years. However, most of the products are still sold under the name of multinational enterprises. There is an emerging vibrant value-adding sub-sector led by the Tea Packers Association, which aims at providing consumers across the world with pure Kenya branded teas. 4.2 Cut flower industry Exports of flowers such as roses have been drastically increasing since late the 1990s; at present, cut flowers constitute the second largest export item after tea. Table 4 Year 1980 1985 1990 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Export volume and value of cut flower industry Volume (Tons) 7,422 10,000 14,425 29,374 35,212 35,853 30,221 36,992 38,757 41,396 52,106 Value (Kshs. Millions) 227 463 940 3,642 4,366 4,900 4,857 7,235 8,650 10,627 14,792 Source: Dolan et al. (2002) Table 4 demonstrates the export volume and the value of the flower exports from 1980 to 2002. In addition, according to Horticulture Crops Development Authority, the export volume of cut flowers was 62,614 tons in 2003, 88,243 tons in 2004, and 81,219 tons in 2005. Since almost all cut flowers are intended for export, the production volume appears to be around the same amount. A recent increase in the production volume is because of the high freight rates from Nairobi; growers have been selecting high value flower types and varieties in order to maintain their market share and enhance their production capacity. Among other flowers, roses are also the most important cut flowers for African producers. They represent 71% of Kenya’s flower production. Table 5 World’s leading exporters of cut flowers (thousands of US$) Countries Netherlands Colombia Ecuador Kenya USA Israel Spain Zimbabwe Italy Thailand Others TOTAL 1992 2,153,560 395,644 25,330 61,477 14,359 146,120 52,665 28,743 111,277 27,579 266,950 3,283,704 1998 2,296,041 600,014 201,883 131,550 20,569 175,196 95,977 61,925 80,158 51,856 369,194 4,084,363 1999 2,095,183 546,210 210,409 141,326 14,762 115,884 85,450 58,810 67,921 50,175 383,313 3,796,443 2000 2,003,393 566,986 215,414 144,441 13,738 102,292 77,407 63,797 58,235 50,042 390,009 3,685,754 2001 Share for 01 2,027,932 55.7% 562,466 15.5% 206,561 5.7% 165,336 4.5% 114,436 3.1% 114,415 3.1% 78,582 2.2% 65,520 1.8% 54,885 1.5% 43,775 1.2% 206,231 5.7% 3,640,139 100.0% Source: Labaste ed. (2005). Although Kenya is an emerging exporter in the industry, the market is still controlled by Holland, the market share of which is still over 50% of the total share. However, among African countries, Kenya has demonstrated an outstanding performance. The Kenyan cut flower industry secures the market in winter—including Christmas and St. Valentine’s Day—when the production in Europe decreases. It complements the supply shortage in the northern hemisphere by utilizing the locations in the southern hemisphere. Similar to tea production, Kenyan cut flower production is situated at high altitudes of 1,500 to 2,000 meters above the sea level; this leads to fewer insect pests and allows the use of minimal amount of pesticides. It is reported that there are few cases of finding insect pests at the plant quarantines of importing countries, as compared to other exporters. Large scale firms internally integrate the processes of production, packaging, and export. In addition, each package is attached with a barcode, which enables traceability. Dutch companies occupy most of the industry, with the introduction of an up-to-date production management technology; moreover, their production is uniform and stable. Among over 500 producer/exporters growing cut flowers in Kenya, the production for export is largely concentrated on approximately 60 medium to large-scale flower operations, of which the 25 largest producers account for over 60 percent of total exports. The larger flower operations range in size from 20 to over 100 ha under production, with a labor force ranging from 250 to 6000. Supplementing these larger growers are approximately 50 medium-scale commercial growers and an estimated 500 small growers. The costs of complying with changing standards have an inverse relation with company size and present a real challenge to small-scale farmers. There has also been growing pressure from nongovernmental organizations for the industry to take bolder steps to preserve the environment. A few flower farms have taken steps to address some of these concerns by building water treatment and water harvesting facilities (World Bank 2004). The industry faces cost-up factors such as the Euro-Retailer Produce Working Group Good Agricultural Practices (EurepGAP) certification, safety certification of agro products exported to the EU, and decline in the share of the EU market by the export expansion of new countries like Ethiopia, which have government’s support such as tax preferences. With regard to the value chain, in contrast to the tea industry, the flower industry mainly specializes mostly in production, while new breeds are developed in Europe. Following Kenya’s accession to the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) in February 1999, the supply of planting material is more readily available from local propagators at present. The starting material for cut flowers and pot plants (cuttings and young plants) is currently strong. Starting material presents good opportunities because of its relatively high value/volume ratio and high levels of labor intensity, which render it impossible for being produced in Europe as yet. Starting material is also a growing supply industry for the international horticultural production sector. Both capital goods (such as materials for greenhouse) and intermediate goods (such as fertilizer) are imported. With regard to input, propagation materials, fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation, and fertilizer application equipment have to be imported from other countries. New sources of special fertilizers for horticulture are India, China, and Singapore. The infrastructure for cut flower production is, in particular, very expensive, and small-scale farmers can often not afford it. However, the improvements in technology have resulted in an increased production per unit area and enhanced the quality of the produce (EPC 2004). Due to the characteristics of the commodity, it is not feasible for small-scale farmers to sell under their own brand name. Therefore, it is important for Kenya or its specific regions to be regarded as flower producing areas in the market. In this respect, it should be noted that Kenya is becoming increasingly popular in Europe. However, some flower producers, including locals, have started moving their production base to Ethiopia; this is because higher altitudes enable the cultivation of bigger flowers, and the government tries to attract investors with preferential measures such as land provision at lower prices and tax exemptions. Moreover, poor value chain deployment boosts the relocation with lower opportunity cost. 4.3 Garment industry in the EPZs The garment industry, as a whole, is occupying only 0.1% of the total export (Central Bureau of Statistics 2006). However, we have included the industry as one of the case study targets because it is dominant in the EPZs and enjoys benefits from AGOA. The value chain flow of the garment industry in EPZ is as follows. The mega retailers in the US decide the design. In accordance with the design, garment producers import fabrics from China or other countries. Fabrics are processed using imported sewing machines, following which, the sample products are checked with imported testing equipment. Finally, the finished products are exported to the US and sold as the retailers’ own brands. In this sense, the industry is a typical enclave. Although Kenya originally had a supply chain of cotton cultivation, yarn-making, and weaving, it was diminished by the liberalization policy of the 1990s. AGOA allowed African countries to utilize imported fabrics; hence, garment manufacturing factories, mainly foreign direct investment, can be located in Africa. Although the US congress has voted to allow Kenya and other eligible African countries to continue using foreign fabrics in the textiles and clothing that they export duty-free to the US, the time given to them—at least another six years, until 2013—is not very long. In ERS, the revival of cotton production was emphasized as one of the two sub–sectors that were specified. The objective was to “revamp growth in the cotton industry and reduce the cost of cotton production to US$ 0.46/1b, consistent with international prices.” However, this target has not been realized, and the prospects for 2007 are weak. 5. Outline of the strategy and action plan for industrial development The three abovementioned industries accomplished considerably good export performances. Tea and cut flower exports depend on the “spatial economic advantage” derived from natural resource endowment including climate (because of latitude and altitude), while the garment industry managed to export with the help of AGOA. We propose the strategy that Kenya should pursue the possibility of fully utilizing its “spatial economic advantage” and extending its impact through the value chain. This is one plausible starting point for further industrialization. Further, Thailand was described as a “newly agro industrialized country (NAIC),” with of its increasing agro industry export. In this context, it was expected that a modernized and internationally competitive agro industry would possibly require domestic, intermediate, and capital good production for accomplishing better quality, cost, and delivery. The cotton industry in the US also underwent a similar experience in the nineteenth century (Wood and Mayer 2001). It is obvious that a NAIC type is not sufficient to develop broad-based industrialization. For broader industrialization, it is crucial to realize and create a considerable impact. In addition, the strategy to strengthen the currently competitive industry might appear to be contrary to the diversification advised by Ng (2005). However, as mentioned below, intermediate and capital goods for agriculture and agro-processing can be exported, particularly to other African countries. By means of this process, we can expect export diversification. The following is a tentative outline of the action plan for industrial development in the event it is necessary to start from scratch, based on the strategy mentioned. 1) Create a niche based on competitive advantage, usually “spatial economic advantage”, in the cases of sub-Saharan countries. 2) Secure international partners such as mega retailers for horticultural products and major multinationals for tea. 3) Realize production to meet the needs of international partners, and ultimately, final consumers. 4) Expand the activity base in value chains, particularly backwards, such as intermediate goods, capital goods, and research and development, in cooperation with international partners. 5) Utilize the operation of a value chain by exporting intermediate and capital goods or modifying them for different domestic industries. In an age of rapid change and stiff competition, changing external conditions are likely to result in the sudden deterioration of the industrial accomplishment. For example, the abolishment of AGOA appears to seriously affect the garment industry in African countries. In addition, these stages might not occur step by step but would rather overlap. For example, it would be more efficient to ask for advice from international partners while selecting the appropriate niche. In that case, the second objective in the action plan should be accomplished before the first. The tea industry in Kenya can be considered to be in the fourth stage; however, it has somewhat stagnated while the cut flower industry is in the third stage and appears to be at a standstill. 6. Further research plan In accordance with the abovementioned discussion, it is necessary to conduct additional research on the industrial development in Africa. The research should aim at identifying the capacity for industrial development and making policy recommendations for Tokyo International Conference on African Development IV (TICAD IV). With regard to the selection of the industry, we have already decided upon the tea, cut flower, and garment industries for further investigation. They are appropriate cases since they have already reached a certain stage (or at least are in the third stage as mentioned in the previous section). It is possible to learn from their experiences in climbing up the ladder, and at the same time, consider the possibility of further development as a feasible objective (for instance, refer to Figure 2 on Kenyan horticulture industry’s position among African countries). More importantly, they already are or are capable of becoming “spatial economic advantage” based, which is suitable for current factor endowment. Figure 2 Kenyan horticulture industry’s position among African countries Advanced production South Africa 2 1 Kenya Morocco Domestic market orientation 3 4 5. Selfsufficiency West African countries such as Senegal, Mali Central Afican countries Small countries like Rwanda, Burundi Source: Labaste ed. (2005). Basic prduction structure Code d'lvolre Egypt East African countries such as Zambia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Uganda Export orientation 1) 2) 3) 4) 1 This research aims to achieve the following. Reinvestigate the experience of the case industries, particularly in terms of CD and its vulnerability to changes in external conditions. Set the overextended but feasible target of export industry development (e.g., growth of a certain percentage over that mentioned in the national plan or attain a certain level of share in the world market). Set the target of CD for realizing the export target—the current capacity level has to be analyzed in detail by conducting questionnaire surveys in the case industries and interviews with key informants such as the government and trade associations. Formulate an action plan for developing the necessary capacity. African countries have accomplished relatively high labor productivity. This derives from the fact that the ratio of capital-intensive industries such as steel, metal products, petrochemicals, beverages, and cigarette is high. In many cases, the concerned firms are run by the government or foreign direct investment. As the result, the wages in the manufacturing sector are also likely to be high. The labor market is divided into one section for the minorities, with fixed and high wages, and the other section for the majorities, with fluid and low wages. However, Kenya’s figures as regards wages are not as high as those in most other countries in the region. 2 As mentioned in the previous section, it is necessary for the target industry to be different from countries other than Asia. However, we would like to emphasize that Africa to learn from Asia in terms of the role of government in industrialization. The industrial policy in the developing countries has been one of the central issues since the 1950s. There have been discussions, mainly between the relatively market-oriented neoclassicals and the intervention-oriented structurists (Lall 2004). Since the mid-1990s, the focus has been on how to evaluate the East Asian experience regarding the success in import substitution and export orientation and its applicability to other developing countries, including Africa. New institutionalist schools that are based on the neoclassical framework but are more intervention-oriented recognized the significance of “market-oriented industrial promotion policies,” such as general export promotion and policy finance. However, they did not agree with the applicability of selective intervention in the form of promoting specific industries, especially to the countries other than East Asian ones (The World Bank 1993). Further, in the recent analysis on industrial cluster development, the government’s role in promoting innovation is limited to general deregulation, incentive measures, and reformation of laws (Yusuf 2004). Some structurists, in Lall’s term, “the technological capabilities approach” intended to adopt the result of evolutionary economics and the economics of information and strengthen the theoretical base with regard to a selective industrial policy. They focus on the technological capability formation process in a broad sense, including marketing (Lall 2004, Westphal 2002). Unlike the new institutionalists, they emphasize that the East Asian experience demonstrates that it is possible for selective intervention to function; however, they admit that it did not work as expected in many countries including Africa. In addition, it failed to support the CD of the private sector because of the government’s lack of capacity. In a broad sense, this difference comes from the difference in the measures undertaken to realize the necessary CD, including social capabilities for industrialization (Minami and Makino 2002). According to new institutionalists, market mechanisms and non-selective interventions such as education and physical infrastructure development would realize CD. The technological capabilities approach emphasizes global sophistication that goes along with selective intervention and the specialization of industrial technology and know-how has boosted the importance of CD. There has been a debate regarding whether the selective interventionist policy is appropriate for enhancing industrial development (Weiss 2002; Lall 2004; Pack 2006). However, according to Lall (2004), all interventions are eventually selective, regardless of whether or not they are intentional. For instance, physical infrastructure and human capital investment, which new institutionalists admit is necessary, is impossible to implement non-selectively. In this sense, we need to consider selectiveness as a precondition. Even though the government plays a role in human capital, research and development, and physical infrastructure, selective effects must be taken into consideration. Hence, selectiveness is still a significant issue, although under the circumstances of liberalization, only a few policies introduced by South Korea and Taiwan can be implemented. Regarding the implementation of deliberate selective measures, we should investigate the possibility of short- and long- term competitive advantage formation, and the target industry should be decided on the basis of these criteria, without selecting the specific industries in advance. This is necessary for avoiding an attempt at rent-seeking. Here, although we already have some limited information for the decision, we need to attempt to implement the process as rationally as possible. Weiss (2002) pointed out that from a fundamental perspective, the developing countries have to secure the institution that sets the common objective, i.e., the economic development between the government and private sector in order to prevent rent-seeking activities and ineffectiveness. 3 Regarding some specific clothing products, AGOA provides Kenya with preferences of up to 35% over those offered to countries facing MFN tariffs. In December 2006, the adoption of AGOA preference to Kenya and other African countries was extended till 2013. 4 Manda and Sen (2006) offered the following argument. Since the 1980s, Kenya has been gradually integrating with the global economy. Using both industry-level and firm-level data, this paper examines the effects of globalization on employment and earnings in the Kenyan manufacturing sector. The industry-level analysis suggests that the overall effect of international trade on manufacturing employment has been negative in the 1990s. The firm-level analysis indicates that the less-skilled workers experienced losses in earnings and there was increasing inequality between the earnings of skilled and unskilled workers during this period. This suggests that in Kenya, globalization has been associated with adverse labor market outcomes. 5 During this period, compared to African countries, Asian countries reformed their economies differently—they initially focused on providing non-traditional export activities, direct inducements, and subsidies. The specific policies employed varied from the export subsidies (in South Korea and Taiwan in the 1960s) to export processing zones (in Singapore and Malaysia in the 1970s) to the special economic zones (in China in the 1980s and 1990s). However, in each case, the focus was more on targeting new export sectors rather than on import liberalization. 6 These findings can be evaluated as emphasizing the increasing influence of mega retailers. Hence, the differences by characteristics of international partners are more evident. 7 According to Bedford et al. (2002), one of the major estate holders has 18,000 employees, of which 90% are tea pluckers. The work force predominantly belongs to a trade union which complies with the Kenyan collective bargaining agreements. The company operates an equal opportunity policy with basic pay at Ksh 135 per day; a good plucker earns an average of Ksh 327 per day. 8 JETRO (2005) highlights other characteristics of Kenyan tea: (1). Most of the foreign companies are currently managing tea businesses in India and Sri Lanka and have implemented quality assurance standards that meet global market standards. (2). East Africa’s tea history is short as compared to those of India and Sri Lanka. Therefore, the equipment in tea factories is more modern, and there are fewer cases of contaminants getting mixed in the tea. 9 The total fertilizer use in Kenya has risen from a mean of approximately 180,000 tons per year during the 1980s to 250,000 tons per year during the early 1990s and over 325,000 tons from 1996–2003. In 2004/05, Kenyan farmers used 351,776 metric tons of fertilizer. At present, commercial fertilizer imports are approximately three times the levels achieved during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Ariga et al. 2006). References Amsden, H. Alice. 2001. The Rise of the Rest: Challenges to the West from Late-industrializing Economies. Oxford University Press. Ariga, Joshua, T.S. Jayne, and J. Nyoro. 2006. Factors Driving the Growth in Fertilizer Consumption in Kenya, 1990-2005: Sustaining the Momentum in Kenya and Lessons for Broader Replicability in Sub-Saharan Africa (Tegemeo Working paper 24/2006). Tegemeo Institute Of Agricultural Policy and Development, Egerton University. Bedford Ally, Mick Blowfield, Duncan Burnett and Peter Greenhalgh. 2002. Value chains: lessons from the Kenya tea and Indonesia cocoa sectors. The Resource Centre for the Social Dimensions of Business Practice (Resource Centre). Report 3. Bienen H.. 1990. The Politics of Trade Liberalisation in Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 38 (4): 713-731. Bigsten, Arne and Peter Kimuyu. 2001. Structure and Performance of Manufacturing in Kenya. Palgrave. Central Bureau of Statistics. 2005. Statistical Abstract 2005. Central Bureau of Statistics. 2004, 2006. Economic Survey 2004, 2006. Collier, Paul. 2000. Africa’s Comparative Advantage. In Jalilian, Hossein, Michael Tribe and John Weiss. Industrial Development and Policy in Africa: Issues of De-industrialisation and Development Strategy. Edward Elgar. 11-21. Dolan, Catherine, Maggie Opondo and Sally Smith. 2002. Gender, Rights & Participation in the Kenya Cut Flower Industry (NRI Report No: 2768, SSR Project No. R8077 2002-4). Natural Resources Institute. Ethical Trade Initiative. 2005. Addressing labour practices on Kenyan flower farms: Report of ETI involvement 2002-2004 (ETI Briefing). Export Processing Zone Authority. 2005. Tea & Coffee Industry in Kenya 2005. Export Promotion Council. 2004. Kenya: Supply Survey on Horticultural Products. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2000. Production Yearbook 2000. Fontaine, Jean-Marc ed. 1992. Foreign Trade Reforms and Development Strategy. Routledge. Gesimba, R.M., M.C. Langat, G. Liu and J.N. Wolukau. 2005. The Tea Industry in Kenya; The Challenges and Positive Developments. Journal of Applied Sciences. 5 (2): 334-336. Humphrey, John. 2006. Shaping Value Chains for Development: Global Value Chains in Agribusiness. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). Japan External Trade Organization. 2005. Programme for East African Tea (Kenya, Tanzania) Report. ICRA. 2006. Industry Report – Food (ICRA Research Analysis). Ikiara, Gerrishon K., Joshua Olewe-Nyunya and Walter Odhiambo. 2004. Kenya: Formulation and Implementation of Strategic Trade and Industrial Policies. In Charles Soludo, Osita Ogbu and Ha-Joon Chang. The Politics of Trade and Industrial Policy in Africa: Forced Consensus? Africa World Press/IDRC. Kinyili, Jacinta M. 2003. Diagnostic study of the tea industry in Kenya. Export Promotion Council. Labaste, Patrick ed. 2005. The European Horticulture Market: Opportunities for Sub-Saharan African Exporters. The World Bank. Lall, Sanjaya. 2004. Reinventing Industrial Strategy: The Role of Government Policy in Building Industrial Competitiveness (G-24 Discussion Paper Series No. 28). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four. McCormick, Dorothy. 2000. Value Chains, Production Networks, and the Business System Preliminary Thoughts with Examples from Kenya’s Textile and Garment Industry (Discussion Note prepared for the Bellagio Value Chains Workshop 25 September - 1 October 2000). Matthews, Ron. 1987. The Development of a Local Machinery Industry in Kenya. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 25: 67-93. Matthews, Ron. 1991. Appraising Efficiency in Kenya’s Machinery Manufacturing Sector. African Affairs. 90:65-88. Minami, Ryoshin and Makino. 2002. Nihon no Keizai Hatten (Japan’s Economic Development). Toyokeizaisinposha (in Japanese). Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Industry. 1999. Fertilizer and Pesticides: Sub-sector Profile and Opportunities for Private Investment. Minot, Nicholas and Margaret Ngigi. 2004. Are Horticultural Exports a Replicable Success Story? Evidence from Kenya and Côte d'Ivoire (EPTD Discussion Paper No. 120, MTID Discussion Paper No. 73). International Food Policy Research Institute. Moss, Todd Moss and Alicia Bannon. 2004. Africa and the Battle over Agricultural Protectionism. World Policy Journal 21(2):53-62. Ng, Francis and Alexander Yeats. 2005. Kenya: Export Prospects and Problems (Africa Region Working Paper Series No. 90). The World Bank. Nyoro, J. K., Maria Wanzala and Tom Awour. 2001. Increasing Kenya’s agricultural competitiveness: farm level issues (Tegemeo Working paper 24/2006). Tegemeo Institute Of Agricultural Policy and Development, Egerton University.. Omolo, Jacob O. 2006. The Textiles and Clothing Industry in Kenya. in Herbert Jauch and Rudolf Traub-Merz eds. The Future of the Textile and Clothing Industry in Sub-Saharan Africa. 147-164. Pack, Howard and Kamal Saggi. 2006. Is There a Case for Industrial Policy? A Critical Survey. The World Bank Research Observer. 21(2): 267-297. Rodrik, D. (2004) Industrial Policy for the Twenty-First Century. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4767. Rodrick, Dani. 2006. Industrial Development: Stylized Facts and Policies. UNU Presentation Paper. Santos-Paulino, Amelia. 2005. Trade Liberalisation and Economic Performance: Theory and Evidence for Developing Countries. World Economy 28(6): 783-821. Swamy, G.. 1994. Kenya: Patchy, Intermittent Commitment. In Hussain, I. and Faruque eds. Adjustment in Africa: Lessons from Case Study Countries. World Bank. Tallontire, Anne. 2001. The implications of value chains and responsible business for the sustainable livelihoods framework: case studies of tea and cocoa. University of Greenwich Wade, R. 1990. Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton University Press. Weiss, John. 2002. Industrialisation and Globalisation: Theory and Evidence from Developing Countries. Routledge. Westphal, Larry E. 2002. Technology Strategies for Economic Development in a Fast Changing Global Economy. Economics of Innovation and New Technology. 11: 275-320. Wood, Adrian and Jörg Mayer. 2001. Africa’s Export Structure in a Comparative Perspective. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 25: 369-394. World Bank. 1993. The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. Oxford University Press. World Bank. 2004. Reducing Poverty Sustaining Growth Scaling Up Poverty Reduction A Global Learning Process and Conference in Shanghai, May 25–27, 2004, Case Study Summaries. Yusuf, Shahid. 2003. Innovative East Asia “The Future of Growth”. The World Bank and Oxford University Press. Hiroshima University, the 21st Century COE Program Hiroshima International Center for Environmental Cooperation Discussion Paper List Vol.2006-5 Murakami, K., Matsuoka, S. and Kimbara T. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) "A Causal Analysis for the Development Process of Social Capacity for Environmental Management: The Case of Urban Air Quality Management" 2006/9/28 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.17). Vol.2006-4 Senbil, M., Zhang, J. and Fujiwara A. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) "Land Use Effects on Travel Behavior in Jabotabek (Indonesia) Metropolitan Area" 2006/8/2. Vol.2006-3 Senbil, M., Zhang, J. and Fujiwara A. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) "Motorcycle Ownership and Use in Jabotabek (Indonesia) Metropolitan Area" 2006/7/30. Vol.2006-2 Nakagoshi, N., Kim, J. and Watanabe, S. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) "Social Capacity for Environmental Management for Recovery of Greenery Resources in Hiroshima" 2006/7/28. Vol.2006-1 Murakami, K. and Matsuoka, S. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) "Empirical Analysis of the Causal Relations between Urban Air Quality, Social Capacity for Environmental Management (SCEM) and Economic Development" 2006/7/10 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.12). Vol.2005-10 Murakami, K., Matsuoka, S. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) An Empirical Study of the Methodology for Assessing Social Capacity : The Case of Urban Air Quality Management, 2006/3/30 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.17). Vol.2005-9 Matsuoka, S., Fuchinoue, H. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Innovation in Development Aid Policy and Capacity Development Approach. 2006/3/1. Vol.2005-8 Matsuoka, S., Fuchinoue, H. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Innovation in Development Aid Policy and Capacity Development Approach, 2006/1/31 (See Vol.2005-9). Vol.2005-7 Yosida, K. (Department of Social Systems and Management, University of Tsukuba) Benefit Transfer of Stated Preference Approaches to Evaluate Local Environmental Taxes. 2006/1/29. Vol.2005-6 Fujiwara, A., Senbil, M., Zhang, J. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Capacity Development for Sustainable Urban Transport in Developing Countries. 2006/1/20. Vol.2005-5 Matsuoka, S., Murakami, K., Aoyama, N., Takahashi, Y., Tanaka, K. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Capacity Development and Social Capacity Assessment, 2005/11/17 (See Vol.2005-4). Vol.2005-4 Matsuoka, S., Murakami, K., Aoyama, N., Takahashi, Y., Tanaka, K. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Capacity Development and Social Capacity Assessment (SCA), 1st ed., 2005/10/24, 2nd ed., 2005/11/17. Vol.2005-3 Murakami, K., Matsuoka, S. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Evaluation of Social Capacity for Urban Air Quality Management, 2005/10/3 (Japanese only). Vol.2005-2 Cheng Ya Qin (China Association for NGO Cooperation) NGO’s Activity and its Role in China, 2005/10/1 (Japanese only). Vol.2005-1 Tanaka, K. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) The Role of Environmental Management Capacity on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from China's Electricity Industry, 2005/9/15. Vol.2004-9 Kimura, H. (Graduate School of International Development, Nagoya University) Present Condition and Prospects on the Social Capacity Development for Environment Management at Jakarta, 2005/3/10 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.28). Vol.2004-8 Kimbara, T., Kaneko, S. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Study on the Relations between Cooperate Environmental Performance and Environmental Management, 2005/3/10 (Japanese only). Vol.2004-7 Honda, N. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Analysis of Causal Structure on Social Capacity Development for Environmental Management in Air Pollution Control in Japan, 2004/10/25 (Japanese only). Vol.2004-6 Kimbara, T., Kaneko, S. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Possibility of Simultaneous Pursuit of Environmental and Economical Efficiency, 2005/3/10 (Japanese only). Vol.2004-5 Honda, N. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) The Role of the Social Capacity for Environmental Management in Air Pollution Control: An Application to Three Pollution Problems in Japan, 2004/6/18 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.14). Vol.2004-4 Matsumoto, R. (Department of International Development Studies, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University) Development of Social Capacity for Environmental Management: The Case of Yokohama City, 2004/5/31 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.17). Vol.2004-3 Yagishita, M. (Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Nagoya University) Evaluation of Nagoya Stakeholder Conference Aimed for the Realization of Environmentally Sound Material-Cycle Society based on Citizen's Participation, 2004/11/15 (Japanese only). Vol.2004-2 Fujikura, R. (Faculty of Humanity and Environment, Hosei University) Role of Stakeholders in the Process of Japanese Successful Pollution Control during the 1960s and 1970s ? Sulfur Oxide Emission Reductions in Industrial Cities ? (Japanese, English Abstract: p.18). Vol.2004-1 Fujiwara, A., Zhang, J., Dacruz, M.R.M. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Social Capacity Development for Urban Air Quality Management the Context of Urban Transportation Planning, 2004/4/20. Vol.2003-3 Yoshida, K. (Graduate School of Systems and Information Engineering, University of Tsukuba) Socio-Economic Evaluation of Urban Ecosystem, 2004/3/31 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.19). Vol.2003-2 Kimura, H. (Graduate School of international Development, Nagoya University) Issues on the Social Capacity Development for Environmental Management under the Decentralization of Indonesia, 2003/11/21 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.20). Vol.2003-1 Matsuoka, S., Okada, S., Kido, K., Honda, N. (Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University) Development of Social Capacity for Environmental Management and Institutional Change, 2004/2/13 (Japanese, English Abstract: p.26).