Elizabethan Underpinnings for Women

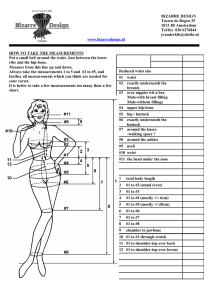

advertisement