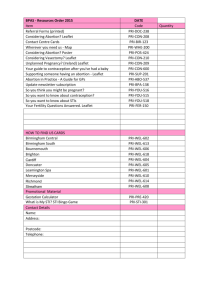

Contraception, Abortion, and Infertility

advertisement