Making & Breaking the Law - 9th Edition

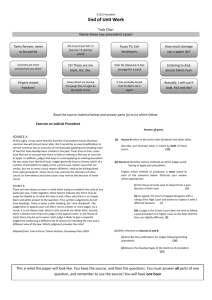

advertisement