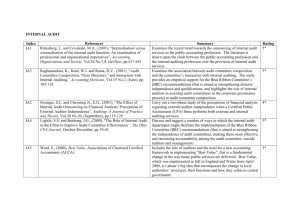

Ethics and Auditing - ANU Press - Australian National University

advertisement