01.Yeast And Mold in Food

advertisement

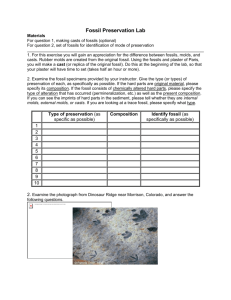

YEAST AND MOLDS IN FOOD The large and diverse group of microscopic foodborne yeasts and molds (fungi) includes several hundred species. The ability of these organisms to attack many foods is due in large part to their relatively versatile environmental requirements. Yeasts tend to grow within food and drink matrices in planktonic form and they tend to ferment sugars, growing well under anaerobic conditions. Molds, on the other hand, tend to grow on the surface of objects in the shape of a visible ‘mycelium’ made up of many cells. Both yeasts and molds cause various degrees of deterioration and decomposition of foods. They can invade and grow on virtually any type of food at any time. They invade crops such as grains, nuts, beans, and fruits in fields before harvesting and during storage. They also grow on processed foods and food mixtures. Several foodborne molds, and possibly yeasts, may also be hazardous to human or animal health because of their ability to produce toxic metabolites known as mycotoxins. Even though the generating organisms may not survive food preparation, the preformed toxin may still be present. Certain foodborne molds and yeasts may also elicit allergic reactions or may cause infections. Although most foodborne fungi are not infectious, some species can cause infection, especially in immunocompromised populations, such as the aged and debilitated, HIV-infected individuals, and persons receiving chemotherapy or antibiotic treatment. This is particularly problematic in plants producing high sugar/low water activity/low pH products. Factories producing fruit products, baked goods, confectionary, and fermented dairy products can be at real risk from yeast and mold contamination. Some Important Food Spoilage Yeast and Mold Species YEASTS Species Foods affected Brettanomyces bruxellensis Beer and wine, fruit yoghurts Debaryomyces hansenii Cured meats and brined products Saccharomyces cerevisiae Soft drinks and fruit juices Zygosaccharomyces bailii Soft drinks, sauces, fruit juice, wine, ciders and syrups Zygosaccharomyces rouxii Confectionery, fruit concentrates C/ La Forja, 9 28850 - Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid - SPAIN Tel. +34 91 761 02 00 Fax +34 91 656 82 28 Some Important Food Spoilage Yeast and Mold Species MOLDS Species Foods affected Aspergillus flavus Nuts and oilseeds (mycotoxin producer – aflatoxins) Aspergillus niger Fresh fruit and vegetables, nuts and seeds, dried foods Aspergillus ochraceus Dried and stored foods (mycotoxin producer – ochratoxin) Byssoclamys fulva Canned fruits Eurotium chevalieri Cereals and a wide range of processed and stored foods Fusrium culmorum Infects cereals, especially barley, in the field (mycotoxin producer – DON and others) Penicillium aurantiogriseum Stored fruits and vegetables Penicillium commune Cheese Penicillium digitatum Citrus fruits Rhizopus stolonifer Fruits, tomatoes and peppers Wallemia sebi Dried and salted fish and other dried foods YEAST Yeast have long been considered the organism of choice for the production of alcoholic beverages, bread, and a large variety of industrial products. All of these products are currently making a huge impact in the agriculture and food industry. Traditionally, yeasts have been very important in the food industry and nowadays it would be almost impossible to imagine a world devoid of fermented products such as wine, beer or cheese. Nevertheless, given their ability to grow at low pH levels, low water activity and even in the presence of some chemical preservatives, they have become a classic food contaminant causing huge losses to the food industry as well as illnesses to consumers. Yeasts are slow growing organisms when compared to bacteria. If yeasts and bacteria were placed in the same optimum environment and both could grow, it is most likely that the faster growing bacteria would quickly outgrow and outcompete the slower growing yeast, becoming the dominant flora. However, if we move outside the ‘optimum’ growth conditions of most bacteria, into environments that are acidic, or of low water activity (high in sugar), then the yeasts have advantage and would rapidly overtake the growth of bacteria. It is in these specialist food niches that the yeast spoilage has become a problem. MOLDS Molds have both positive and negative effects on the food industry the same way that yeasts do. Some molds are perfectly safe to eat and, in some cases, even desirable (the classic example would be cheese made with mold, such as blue, Brie, Camembert, and Gorgonzola). Other molds can be quite toxic and may produce allergic reactions and respiratory problems, or produce poisonous substances called mycotoxins. Aspergillus mold, for instance, which is most often found on meat and poultry (as well as environmentally), can cause an infection called aspergillosis, which is actually a group of illnesses ranging from mild to severe lung infections, or even whole-body infections. One of the greatest concerns regarding mold in food is the mycotoxins that some varieties produce. One of the most researched mycotoxins is aflatoxin, a cancer-causing poison. C/ La Forja, 9 28850 - Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid - SPAIN Tel. +34 91 761 02 00 Fax +34 91 656 82 28 ISO 21527-1 Dextrose Chloramphenicol Agar (YGC) (Cat. 1301). Selective agars for yeasts and molds usually contain antibiotics to help suppress bacterial growth. Plates are typically incubated at 25 ºC for 5 to 7 days and then examined for the presence of yeast and mold colonies. There are a number of ISO horizontal methods for the enumeration of yeasts and molds in foods and animal feed. ISO 21527:2008 is published in two parts. Part 1 relates to food and feed samples with water activity of >0.95, while part 2 specifically applies to dried and processed foods with reduced water activity of <0.95. Individual yeast and mold species can be isolated from selective agars by subculturing onto a non-selective agar such as Malt Extract Agar (Cat .1038) or Potato Dextrose agar (Cat. 1022). Although it may be possible to recognise some molds at the genus level simply by colony morphology and the appearance of conidia and other features under the microscope, identification at the species level is very difficult and requires specialised skills and experience. These methods typically employ a surface plating technique, where a known quantity of the sample, or the initial suspension, is spread over the surface of a suitable selective agar medium. ISO 21527-1 recommends Dichloran Rose Bengal Chloramphenicol Agar (DRBC) (Cat. 1160). Other media used include Oxytetracycline Glucose Yeast Extract Agar (OGYE) (Cat. 1527) and Yeast Extract Rose Bengal Agar + Chloramphenicol + Dichloran (DRBC Agar) (Cat.1160) (Peptone /Glucose / Monopotassium Phosphate Magnesium Sulfate / Chloramphenicol / Rose Bengal / Dichloran / Bacteriological Agar) Rose Bengal inhibits growth of bacteria and limits the size and height of faster-growing ones molds Dichloran prevents the fast spreading of mucoraceous fungi and restricts size of the colonies of other Chloramphenicol is a wide spectrum antibiotic Incubation at 25ºC±1 and observed after 3,4 and 7 days BIBLIOGRAPHY Valerie Tournas, Michael E. Stack, Philip B. Mislivec, Herbert A. Koch and Ruth Bandler. BAM: Yeasts, Molds and Mycotoxins. U.S. Food and Drug Administration YeastBook. (2011) A comprehensive compendium of reviews that presents the current state of knowledge of the molecular biology, cellular biology, and genetics of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics Barnett, H.L. 1960. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi, 2nd ed. Burgess, Minneapolis. Molds on food: Are they dangerous? U.S. Department of Agriculture http://www.fsis.usda.gov/Fact_Sheets/Molds_On_Food/i ndex.asp. Accessed June 30, 2012. Lodder, J. 1970. The Yeasts, a Taxonomic Study, 2nd ed. North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. www.condalab.com C/ La Forja, 9 . tech.export@condalab.com 28850 - Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid - SPAIN Tel. +34 91 761 02 00 Fax +34 91 656 82 28