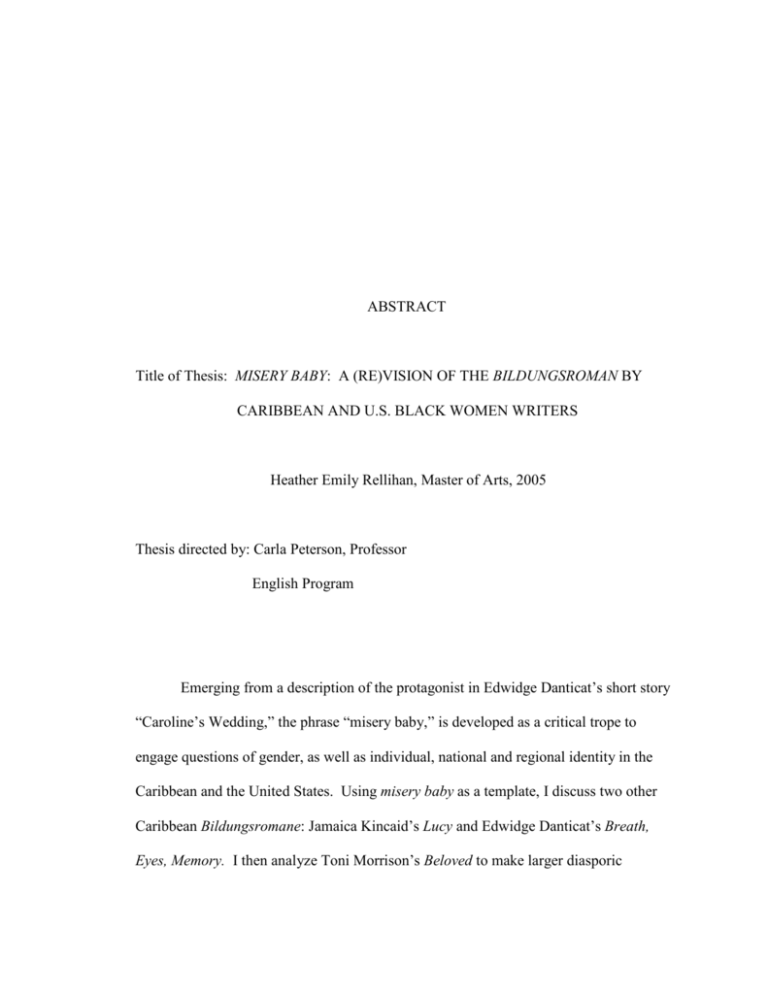

umi-umd-2436 - DRUM - University of Maryland

advertisement