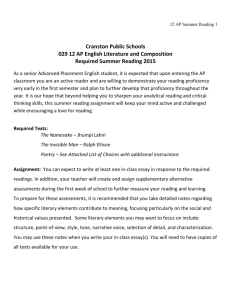

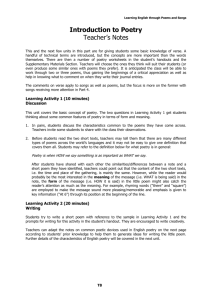

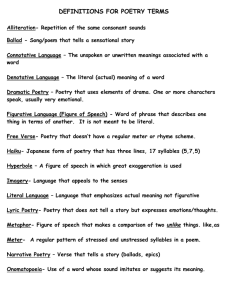

Poetry Teaching Resource: Forms, Devices, and Activities

advertisement