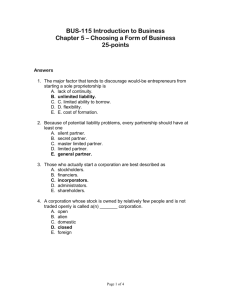

Corporate Liability for Unauthorized Contracts

advertisement