Full Report - Arts, Health, and Seniors Project

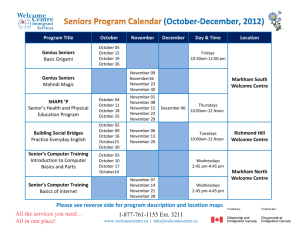

advertisement