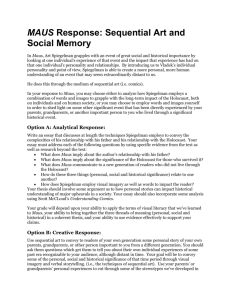

MAuS: A Memoir of the Holocaust - Vancouver Holocaust Education

advertisement