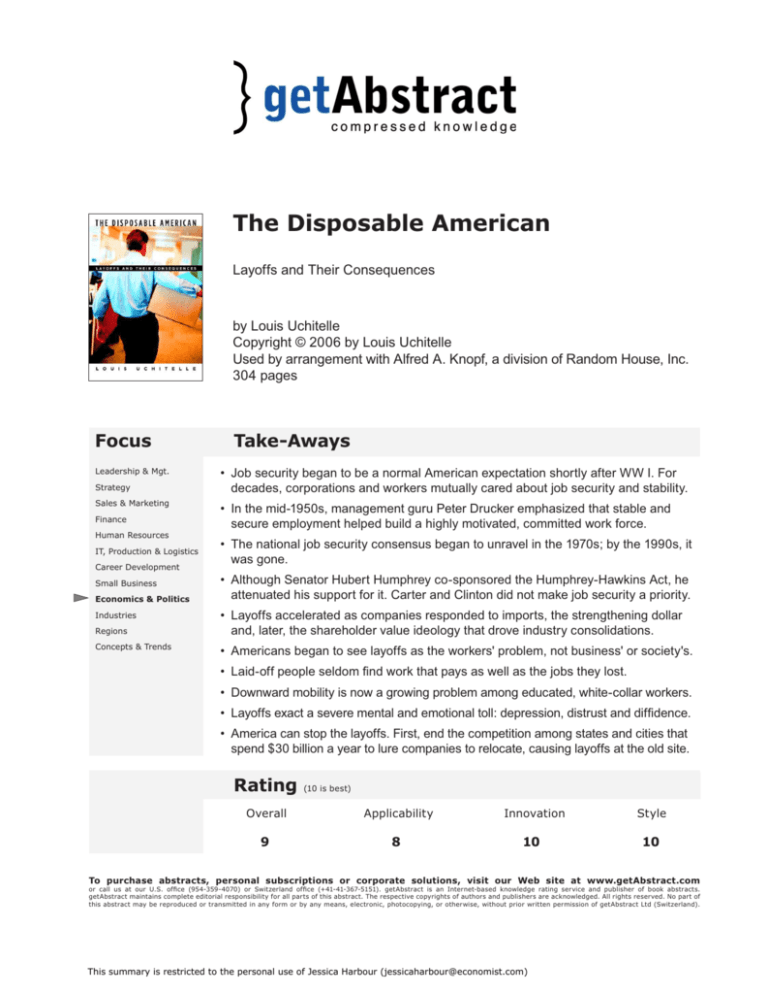

The Disposable American

Layoffs and Their Consequences

by Louis Uchitelle

Copyright © 2006 by Louis Uchitelle

Used by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

304 pages

Focus

Leadership & Mgt.

Strategy

Sales & Marketing

Finance

Human Resources

IT, Production & Logistics

Career Development

Small Business

Economics & Politics

Industries

Regions

Concepts & Trends

Take-Aways

• Job security began to be a normal American expectation shortly after WW I. For

decades, corporations and workers mutually cared about job security and stability.

• In the mid-1950s, management guru Peter Drucker emphasized that stable and

secure employment helped build a highly motivated, committed work force.

• The national job security consensus began to unravel in the 1970s; by the 1990s, it

was gone.

• Although Senator Hubert Humphrey co-sponsored the Humphrey-Hawkins Act, he

attenuated his support for it. Carter and Clinton did not make job security a priority.

• Layoffs accelerated as companies responded to imports, the strengthening dollar

and, later, the shareholder value ideology that drove industry consolidations.

• Americans began to see layoffs as the workers' problem, not business' or society's.

• Laid-off people seldom find work that pays as well as the jobs they lost.

• Downward mobility is now a growing problem among educated, white-collar workers.

• Layoffs exact a severe mental and emotional toll: depression, distrust and diffidence.

• America can stop the layoffs. First, end the competition among states and cities that

spend $30 billion a year to lure companies to relocate, causing layoffs at the old site.

Rating

(10 is best)

Overall

Applicability

Innovation

Style

9

8

10

10

To purchase abstracts, personal subscriptions or corporate solutions, visit our Web site at www.getAbstract.com

or call us at our U.S. office (954-359-4070) or Switzerland office (+41-41-367-5151). getAbstract is an Internet-based knowledge rating service and publisher of book abstracts.

getAbstract maintains complete editorial responsibility for all parts of this abstract. The respective copyrights of authors and publishers are acknowledged. All rights reserved. No part of

this abstract may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of getAbstract Ltd (Switzerland).

This summary is restricted to the personal use of Jessica Harbour (jessicaharbour@economist.com)

Relevance

What You Will Learn

In this Abstract, you will learn: 1) How layoffs became a pervasive, corrosive fact of

American work life; and 2) What the United States can and should do about them.

Recommendation

This excellent book examines the phenomenon of job insecurity in America. Author and

newspaper reporter Louis Uchitelle traces the development and decline of the American

expectation of stable, remunerative, virtually lifetime employment. Republicans may have

taken the boldest steps in rolling back the expectation of job security (Ronald Reagan’s

firing of the air traffic controllers spoke eloquently for the new order), but they did not do

so alone or unopposed. Democratic presidents and politicians did not make preventing

layoffs a major campaign issue or administrative priority. Uchitelle writes smoothly and

evocatively, particularly about the individual experiences of laid-off workers, for whom

the surviving avenues of American opportunity were dead ends. getAbstract recommends

this book to anyone who wants to know what killed the historic American trust between

workers and employers, and how to staunch the bleeding caused by layoffs.

Abstract

“Layoffs became

the measure

of our national

retreat from the

dignity that had

been gradually

bestowed on

American workers

over the previous

90 years.”

“Core workers…

perform the

essential, profitmaking functions

– (like) design

and engineering

at an aircraft

manufacturer

– while peripheral

employees did

support functions:

human resources,

accounting,

clerical work,

customer

service…They

were disposable.”

From Security to Insecurity

Layoffs have become such a large part of American economic life that it is hard to

recall when they were rare. During most of the twentieth century, job stability was the

norm. Peter F. Drucker’s 1950s classic, The Practice of Management, outlined a tradeoff: management built a dedicated workforce by being loyal to its workers. He saw job

stability as essential to corporate success. But 40 years later, Drucker is writing about

“knowledge workers” adrift in an unstable economy where no one expects a permanent

job. They rent out their intellects for short-term assignments, moving along as their needs

– and their employers’ needs – change.

The shift from enjoying stable, lifelong employment to facing ongoing job insecurity

has taken a severe, usually uncalculated toll on the American worker’s economic and

psychological well-being. Laid-off people rarely secure employment that pays as well as

the jobs they lost. Although the layoffs usually are not their fault, they still suffer severe

psychological and emotional pain. When employers tell them that the work they took

seriously and did well for many years is of no consequence, is unnecessary, and is even a

distraction to their firms, they lose their dignity – a difficult wound to repair. Commonly,

layoffs spur strong psychological reactions, including distrust, depression and diffidence,

scarcely suppressed anger and fear of future layoffs.

The idea of having a permanent job started after WWI. In the 1800s, the norm was

mobility. People who lost or left one job could move along and easily find another. The

frontier promised opportunity. Immigrants from Europe expected to find work, but did

not expect to spend their entire working lives at one job. As the frontier closed, the jobless

wanderers who once had been “pioneers” became “tramps.” Immigrants’ children built

new communities around the factories that employed their parents, and went to work in

the same factories, as did their own children. Attitudes toward jobs changed. If you lost

The Disposable American

© Copyright 2006 getAbstract

2 of 5

“While America’s

best engineers

and scientists had

put much of their

energy into the

nation’s military

industries, their

counterparts

in Europe and

Japan…

concentrated on

becoming masters

of production for

civilian purposes.”

“Each layoff

became the

victim’s problem,

not society’s,

or the victim’s

fault, and once

people shifted to

this view, their

employers were

free to incorporate

layoffs into their

tactics and

operations.”

“Everything you

think is important

and do for your

life’s work, isn’t.

To have someone

senior in the

company say that

so bluntly in public

is terrible.”

“When you sever

the connection to

a long-held job,

you are destroying

something that

you can’t restore,

not quickly.”

[ – economist

Louis S. Jacobs]

a job, finding new work was not so easy. Labor unions contributed to the demand for

security and dependable employment. Job stability was a cause worth fighting for, but

it also worked in favor of growing mass-market corporations. They needed employees

who understood their inner workings, norms, practices and culture, which take time to

learn. Knowing that productivity requires a loyal, stable workforce and that loyalty must

be mutual, companies favored long-term employment.

Labor, management and society reached a consensus that job security and stability

were valuable. Employees could count on pensions, retirement funds, medical benefits

and other perquisites of job security, based on years of service. Layoffs were rare, not

unthinkable, but shocking.

How times have changed. While U.S. innovation and creativity focused on Cold War

military industries, European and Japanese competitors applied their ingenuity to civilian

products and technologies. As their economies recovered and their companies grew,

they gained market share. Eventually they entered the American market, challenging

U.S. corporations at home, and winning. Meanwhile, the Bretton Woods financial order

collapsed, ushering in an era of financial deregulation. The oil price shocks boosted fuelefficient Japanese and European cars, an advantage multiplied by the currency markets.

The devastatingly strong dollar of the early ‘80s took a serious toll on U.S. industry,

making American products much more expensive than goods from elsewhere. Whole

industries disappeared. The term “rust belt” emerged to describe ruined mill towns that

had been built on the foundation of job stability.

Corporate raiders targeted the twentieth century’s great companies. They attacked

corporations to unlock shareholder value, extruding money by breaking up, selling

off, downsizing and doing more with less. They demanded that managers justify every

investment, expense and activity in value-to-shareholder terms. Few companies could.

Prodded by capital market disciplinarians, managers came up with the idea of a core-andperiphery. The core business consisted of activities that created a company’s competitive

advantage and market differentiation: design, new product differentiation and marketing.

Everything outside the core – information technology, personnel services, bookkeeping,

payroll – was peripheral, and best left to experts. Thus, spin-offs and outsourcing became

new U.S. business strategies, bringing more layoffs, along with employee transfers and

the use of temporary workers.

A few decades earlier, an educated, productive worker could expect a job for life.

Now, education and productivity were – if not irrelevant – no guarantee. Even formal

guarantees, such as union contracts, became shaky. Right-to-work laws undermined the

unions, especially in the South. Companies could violate some labor protection laws

because no one enforced them. They could even fire strikers and replace them with new

workers, once called “scabs.”

Politicians who might have protected job security failed to do so. Rep. Augustus Hawkins,

of Los Angeles’ Watts ghetto, wrote the “Humphrey-Hawkins Act” to mandate full

employment. Sen. Hubert Humphrey co-sponsored the bill, which originally called

for the government to act as employer of last resort. Hawkins faced serious challenges

to his bill’s economic underpinning. In the 1970s, Humphrey cut back his support

as he came to see inflation as a greater problem. Jimmy Carter, elected in 1976, was

unenthusiastic about the legislation.

The Disposable American

© Copyright 2006 getAbstract

3 of 5

“The trauma of

dismissal – ‘the

acuteness of

the blow,’ as

Dr. Theodore

Jacobs…put it

– unwinds lives

in its own right,

damaging selfesteem, undoing

normal adaptive

mechanisms.”

“In various

small, peripheral

ways layoffs can

be reduced, or

at least made

less painful.”

“The growing

presence of temps

and contract

workers…more

than 10% of the

nation’s workforce,

up from two to

three percent

30 years ago

– is evidence of

a reorganization

of the workplace

to accommodate

layoffs without

having to call

them that.”

“Then there is

the netherworld

of jobs that are

so poorly paid

and so stripped

of opportunity

(no promotions,

no raises, no

training) that

quitting them or

being laid off are

roughly the same.”

Some say this change happened because the American mood turned from communal

to individualistic. Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1980 tolled the final knell for job security

and anti-layoff sentiment. When aircraft controllers struck, Reagan fired them and

hired permanent replacements. He set a precedent that companies quickly copied.

Indeed, corporations were under severe competitive pressure, losing sales and market

share domestically and abroad because of the strong dollar. They, arguably, had little

alternative to closing and laying off workers – at least initially.

But extensive layoffs bred anxiety in the electorate, and anxiety turned to anger when

people saw clearly that Wall Street was profiting enormously from corporate restructuring.

Junk bond mergers and acquisitions left many workers worse off as they made a few wellconnected executives enormously wealthy. In 1988, Congress finally acted, however

meekly, by passing the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act. The act

mandated 60 days warning before companies closed a facility or laid-off as many as 500

workers. Reagan signed the legislation with no enthusiasm – in fact, he disagreed with

it. The law helped take layoffs out of the political limelight during the 1988 presidential

campaign, in which Republican Vice President George H.W. Bush defeated Democrat

Michael Dukakis. Subsequently, layoffs all but disappeared from political discourse.

William Clinton’s 1992 election did nothing to protect jobs. Neither Clinton nor Treasury

Secretary Robert Rubin paid much attention to layoffs. Indeed, they apparently saw

employment as the employers’ concern, not the government’s. Nobel laureate Joseph E.

Stiglitz, chairman of Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, often favored government

intervention in the economy – but not to stop layoffs. He felt there was no way government

intervention to prevent layoffs would improve the lot of everyone in the economy. Indeed,

he believed that the only alternative to layoffs was protectionism, which was unacceptable.

The administration professed to believe – contrary to evidence and experience – that

education and retraining would be sufficient to address the problem of layoffs.

The Problem with Education and Retraining

In the early 1990s, United Airlines took over a state-of-the-art aircraft maintenance

facility in Indianapolis. Thanks in no small part to massive government subsidies, United

used the facility to service its own planes and, eventually, began to service America

West’s planes also. Although employment levels at the facility never reached the numbers

United had spoken of when it negotiated its subsidies, thousands of unionized, skilled

people worked there.

During the early ‘90s, times were good. There was plenty of work for all. However, a

labor dispute in 1999 resulted in a slowdown that sent the maintenance facility into a

tailspin. America West looked elsewhere. United itself, leery of the union’s power at

this facility, decided to diversify its maintenance arrangements. Then, United fell into

financial straits, declared bankruptcy and laid off all the mechanics at the facility.

Despite being highly trained, the overwhelming majority of these mechanics were unable

to find new jobs paying anything close to what they had earned from United Airlines.

Much of the airplane service business migrated to service providers in the South, where

wages were as little as half of Indianapolis union wages. This sort of experience is not

only a blue-collar phenomenon. Similar layoffs affected thousands of workers. Many

white-collar workers ended up with sad stories to tell, including:

• A Citibank human resources executive, laid off after decades of service, was unable

to find employment at comparable pay.

The Disposable American

© Copyright 2006 getAbstract

4 of 5

• A successful Connecticut bank executive in his 50s was replaced by a 22-year-old who

worked for much lower pay. The executive wound up running a welcome station for

tourists entering the state, a position much lower in pay and status than his bank job.

• An information technology and human resource executive for Procter & Gamble

who accepted an early retirement package in anticipation of a layoff, was never able

to find employment even close to her P&G salary level.

“Stable jobs and

sufficient incomes

and stable

communities

are powerful

equalizers.

Restore them

– or begin to

restore them

– and the political

influence that

wealth now buys

and that distorts

democracy will be

easier to unwind.”

“Each job saved

is a victory and

each victory brings

people together

in the mutual task

of resurrecting

the obstacles to

layoffs that once

protected us and

lifted our dignity.”

The euphemism “income volatility” describes this downward mobility. Once, it applied

mainly to workers who lost high-paying factory jobs and were unable to find similarly

paid work. However, in recent years, white-collar workers have seen their incomes fall

permanently for the same reason. This kind of income volatility is a big factor in the

stagnation and decline of U.S. workers’ incomes. Training and re-education only solve the

problem when they lead to other jobs offering equivalent pay. That is seldom the case.

Moreover, the consequences of layoffs and unemployment are not entirely financial. They

take a severe emotional and psychological toll. Unemployment is clearly associated with

depression, which may be exacerbated by the loss of social networks and self-esteem.

People who are laid-off carry the wounds and pain of the job loss experience for years,

and are often unable to pick up the pieces and put their lives together again.

What Is to Be Done

America must address the problem of layoffs and job loss in a broader context. Without

job stability, income security and community stability, wealth can seize possession of the

democratic political process – as it has in recent years. America does not have to tolerate

the wave of layoffs. One good first step would be to end the competition among municipal

and state governments that spend $30 billion a year subsidizing companies to locate

or relocate into their jurisdictions. These expenditures increase layoffs, because many

companies lay off workers in their old locations when they move. A revitalized labor

movement and additional public investment to create jobs would increase employment

security, but both are unlikely to happen.

To solve the problem of layoffs, first consider its magnitude. Current unemployment

statistics undercount the actual number of unemployed by ignoring those who have given

up looking for jobs. Everyone unemployed should be counted, and all layoffs should be

reported. The census refers to layoffs, but people who were laid off twice or more in three

years are only counted as being laid-off once. The U.S. doesn’t count early retirements as

layoffs, although they often are. It doesn’t count outsourcing that transfers a company’s

employees and outside units, although such arrangements are tantamount to layoffs

because lower pay and benefits at the new units lead many people to quit. Companies

should be required to file audited employment reports similar to their financial reports,

specifying how many people left during each period, why, and whether the departures

were voluntary or involuntary. Such measures would improve the available data, enabling

policies to be developed to confront the problem of layoffs in America.

About The Author

Louis Uchitelle has covered economics for The New York Times since 1987, focusing on

labor and business issues. He shared a major award for its 1996 series “The Downsizing of

America.” He also taught journalism at Columbia University’s School of General Studies.

The Disposable American

© Copyright 2006 getAbstract

5 of 5