The Changing Kingdom of Coors

170

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

CASES

CASE 6-1 A CLASSIC: THE CHANGING

KINGDOM OF COORS

Times change. Organizations change in structure, in the products or services they provide, in their scope, in the values projected by their leaders, and in the public impression they wish to convey. Sometimes change is evolutionary, as with organizations committed to clothing fashions, automobile design, or nutritional and health values. Sometimes change is sudden or drastic, as in bankruptcy, change of owners, or a catastrophic event.

The public relations function, by whatever name, is an agent for change within an organization. Two-way interpretation of the organization’s relationship to the greater public good, and the use of two-way communications to adjust an organization to the publics on which it depends for success or failure, can be expected to change over time in form and emphasis. The necessity for interpretive input and output, and for reconciliation of public and private interests, never goes out of style.

Change and adjustment characterize the dynamics of almost any organization, large or small, local or national, competitive or nonprofit, private or governmental.

Making adjustments to changing conditions will constitute part of every practitioner’s career regardless of the organizations served. For our classic example of a company’s adaptation to change, we turn to the

Adolph Coors Brewing Company, a consumer-oriented organization with a philosophical mind of its own. Its basic product is widely known and consumed.

A MAVERICK AMONG BREWERS

For many years Coors operated contrary to some of the most widely accepted textbook ideas about what constitutes success in financing and running a business and in marketing its products. The differences were enough to raise some eyebrows—and some envy—within the beer industry, and in business circles generally, not to mention the consternation caused among politicians whose approach to public issues was generally moderate and safe. Coors, as a company and a family, was outspoken. The prognosis by qualified analysts was not optimistic. Yet few products in America can claim the mystique of Coors beer. Demand was so great that until the “Beer Wars” of the late

1970s—when marketing came into the staid industry in a big way—Coors actually had to ration its beer to wholesalers. Travelers to states where it was sold brought it home in their luggage as treasured contraband. A popular 1977 movie, Smokey and the Bandit, was about a trucker illegally bootlegging a whole trailer of Coors into a state where the company did not distribute its products.

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

171

IMAGE VERSUS REPUTATION

An image is false, not real. Consider a snapshot, which is an image of the person photographed and not the person.

Reputations are based on experience with a product, service, or company—or the expression of trusted comrades.

Which would you rather have—a good image, or a good reputation?

THE COORS STORY FROM

THE BEGINNING

The original Adolph Coors—a quiet, private man—was born in Rhenish Prussia in 1847.

He was taken to Westphalia and at the age of 15 was apprenticed as a bookkeeper. Five years later, he left and worked for breweries in Berlin and Kassel. Orphaned, he set out for the United States in 1868. He worked off his passage in Baltimore, went to Chicago and worked first on the Illinois-Michigan

Canal. Later he became a brewery foreman in nearby Naperville, Illinois. In 1872, at age

25, he was attracted to Denver, where he entered business bottling wines and beer.

Before the year was out, he sold that business. He and Jacob Schueler purchased a brewery site in Golden, Colorado, in the

Rocky Mountain foothills a few miles west of Denver. The brewery was opened in 1873, three years before Colorado joined the

Union.

Times were lean from 1917 to 1933 partly because of prohibition and the

Depression but the company survived by producing malt and other items. When prohibition was repealed, Coors was ready.

Adolph Coors, Sr., died in 1929, but family management continued. By 1958,

Adolph Coors III had become chairman of

Adolph Coors Brewing Company and its subsidiary, Coors Porcelain. In 1960, however, Adolph III died at the hands of a kidnapper. His brother William, second son of

Adolph Jr., and president of Coors, took command. His brother Joseph headed the

Coors Porcelain Company. By this time,

Coors had become the fourth largest U.S.

brewer.

SUCCESS IS WHAT YOU MAKE IT

Some characteristics set Coors apart from other family businesses:

1.

Coors had been a regional company, limiting its sales to 11 states. The brewers ahead of it were national in their distribution. Thus, for Coors to attain fourth rank nationally, its acceptance in those 11 states had to be phenomenal, running as high as

40 percent of the market.

2.

A barrel of beer weighs more than

260 pounds. Nearly 11 million barrels, traveling an average distance of

900 miles each, add up to a lot of transportation expense. Still, Coors had one brewery, the world’s largest, in Golden, rather than several closer to major market areas.

3.

In attaining its size, the company had refused to borrow money. Growth had been financed out of earnings.

4.

Coors production was remarkably integrated vertically; the firm built most of its own packaging, brewing, and malting equipment and produced its own beer cans. It also operated a

172

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations major transportation company to move its beer to market and a small railroad to move items around its extensive plant site.

5.

Coors’s management style was informal, to the point that employees called the president by his first name.

Bill Coors resembled a professional football coach in the off-season, working with cuffed shirtsleeves in a spartan office that contained an extra desk for his brother Joe.

6.

Employee tenure was long, with attitudes generally characterized by pride and loyalty, in a family spirit. Supervisory employees didn’t “go to work at Coors,” they were “with” Coors.

Executives were “Coors executives,” almost as if indentured. Salaries were good, “for the locality.” There were not some of the usual fringes such as bonuses associated with profitability.

Promotion from within was the policy.

All eleven members of the company’s board were full-time employees. The use of outside experts tended to be avoided.

7.

The company hewed to its own value standards and spoke its mind in public issues. Coors family values—austerity, dedication to hard work, honesty, pride in the best-quality product possible, and a rugged individualism that valued highly personal and corporate prerogatives—had been handed down from generation to generation.

Sometimes, however, these values led to misunderstandings and accusations.

1

8.

When it came to the use of communications for marketing, Coors admitted that its Coors Banquet Beer was “the most expensively brewed beer in the world” and felt that this fact kept the demand greater than the supply without shouting about it. Its advertising had been “less than $1 a barrel,” or a fraction of what major competitors spent. Here again, the do-ityourself philosophy prevailed. An inhouse staff prepared what ads and promotional pieces were used.

COORS PRESS AND PUBLIC

RELATIONS

Coors’s public relations was inhibited by a tight-lipped, reactive attitude where financial or competitive information was involved. Because the company was familyowned and sought no outside funding, there was no need for management to reveal these matters and no self-interest benefit.

The few investors to whom an accounting had to be made could, theoretically, gather for dinner at Bill’s or Joe’s house.

The policies of promoting from within and avoiding the use of outside experts tended to eliminate publicity or public relations projects that might have the objective of attracting executive recruits. The employment of thousands in Golden, coupled with the Coors family’s civic and charitable contributions in the Golden-Denver area, left little for public relations professionals to deal with in community relations.

In public affairs and on public issues, the brothers were both “the corporation”

1 On one occasion, the FTC had charged Coors with some heavy-handed sales techniques when they refused to sell draft beer to bars unless they carried it exclusively and in insisting that wholesalers not cut prices. Referring to this episode, Fortune magazine said, “Bill Coors is astonished that anyone would challenge his control over his product, and he vows to fight all the way to the Supreme Court.” Later, the FTC ruled that the company had “illegally restrained competition.” At that time, Bill Coors put his position to a Wall Street Journal reporter this way: “If we have to, we’ll take over distribution ourselves, and Coors will become the biggest beer distributor in the world.”

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

173

and the “corporate view.” They need not wait for a consensus, nor need they use indirect channels in addressing the community, the trade, or local or federal officials.

In product marketing, with one product, the publicity thrust was to enhance the mystique of success. Elements of production were mountain spring water, Moravian barley, Californian and Southern rice, modern brewing equipment, shipment under refrigeration, and the resulting light pilsner brew.

By putting all this together, or perhaps by a process of elimination, the public relations function could properly have been called the “public service information function,” performed if, as, and when requested.

A SHIFT OF TACTICS IN THE MAKING

By the mid-1970s, there was good reason to conclude that Coors had better make some changes in attitudes and tactics or go down the competitive tube. Events had hit Coors like a series of jabs to the face and body.

Among them:

1.

A union boycott starting with a strike had harmful echoes due to contentions that Coors discriminated against African-Americans, Hispanics, and females in employment.

2.

Anheuser-Busch, by aggressive marketing, had cut deeply into Coors’s domination of some major markets such as California. Other brewers responded to Budweiser’s and

Miller’s bold marketing—and the

“Beer Wars” were on. Initially, Coors declined to join in, which resulted in loss of market share.

3.

Light, lower-calorie beer had caught on, and Coors had no entry in the field.

4.

Coors had come up with a punch-top can opener that gave customers more problems than the familiar flip-top openers of competitors.

5.

The trend was to fewer brewers, mainly national in scope, as local beers fell by the wayside.

6.

Anticipating the inheritance tax requirements, the company had to go public, raising the possibility of outside shareholder voices in its decisionmaking process. All voting stock, however, remained with the family.

7.

Some of management’s right-wing views, expressed mainly by President

Joe Coors (a member of Ronald

Reagan’s “kitchen cabinet”), and widely reported in the news, were of no help in broadening public support in the consumer market.

SYMPTOMS OF A TURNABOUT

BECOME VEHICLES

Led by public relations and marketing departments, several significant actions were taken to reverse the business downslide and bid for broad public support.

A lengthy Wall Street Journal article put it this way:

The company has embarked on an elaborate image-building campaign, running nostalgic ads about corporate history and messages beamed at ethnic minorities, homosexuals, union members, women’s rights activists and others who may be harboring ill will against Coors.

The campaign also includes a telecommunications course for Coors executives—traditionally distrustful of the media—who are subjected to intense baiting by communicators simulating

“obnoxious reporters.” The notion is to condition the managers to project charm, humility and control for real interviews.

2

2 John Huey, “Men at Coors Beer Find the Old Ways Don’t Work Anymore,” The Wall Street Journal , January 19, 1979.

174

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

Another tactic was the disarming public admission of past arrogance, articulated by the new generation of Coors management, Jeff, then president of operations, and

Peter, then president of marketing and administration.

On the product front, Coors introduced a low-calorie light beer. An outside advertising agency was retained, and a budget of some $87 million was allocated for advertising and promotion. It has since grown to over $200 million.

This new approach encouraged the company to become more involved on the public relations front. Candor and visibility replaced “no comment” and low profile.

Coors was out in the open competitively, and on the record publicly.

3

A Corporate Public Affairs Division took shape. Its charter, publicly stated, was to appraise employee, public and government attitudes, problems and opportunities . . . initiate and improve programs developing an economic, social and political climate which will assist [in operating] profitably, thereby enabling employees and community neighbors to work, enjoy life, and prosper.

Implementation of the charter in the form of charitable contributions and donations, as one example, was explained in a booklet

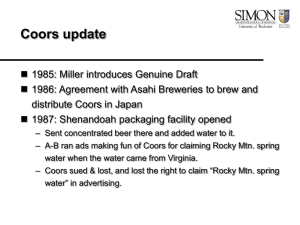

(See Figure 6-1).

Coors’s ultimate objective was linked to public relations— to building, or rebuilding, relationships that would let its products speak for themselves in the marketplace.

For public relations staff, the goal was “removing the political litmus test” that seemed to surround all the company’s actions. The focus was on the boycott.

4 As with any program seeking to attain a turnaround of

180 degrees, there were bound to be some communications hitches along the way.

THE BOYCOTTS

The first boycott started in 1960 when the

Coors family donated a helicopter to the

Denver Police Department, which was under criticism (as were many white majority city police departments) for allegedly trying to keep minorities in the ghettos.

For a variety of reasons, Coors employees voted to decertify their union. In 1977 the

AFL-CIO called for a boycott of Coors products supposedly because of the company’s practice of using lie detector tests in employee investigations and hiring. Several contractual issues were mentioned as well— because the unions wanted to regain their position at the company. This boycott ended in 1987 when labor agreed to stop it if Coors would hold a union certification election.

(Workers voted not to have a union.)

In 1984, Chairman Bill Coors seemed to put a blemish on some of the views that they had worked so hard to change. Speaking off the cuff in a speech at a seminar of the minority Business Development Center in

Denver, Coors said that Africa’s economic problems stemmed from a lack of intellectual capacity. This comment caused a furor in some quarters and reenergized the boycott. Coors sued the Rocky Mountain News because the headline that made the charges was not supported by facts in the story itself.

(An out-of-court settlement resulted.)

3 By 1984, outside counseling services used had included Manning, Selvage and Lee; Carly Byoir and Associates;

The Johnston Group; and Jackson Jackson & Wagner.

4 Of special interest, in 1983 Coors welcomed the CBS 60 Minutes program to look into allegations of bias toward unions and minorities long plaguing the company. Host Mike Wallace found the charges against the company basically untrue. Public relations director Shirley Richards and her staff had shown how to defang the tiger by openness and absolute candor.

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

175

FIGURE 6-1 Coors’s community giving program has flourished and expanded, addressing many community needs.

(Courtesy of Coors Brewing Company.)

176

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

Many distributors and marketers felt the boycott was thwarting their best efforts.

Historically, however, product boycotts are rarely effective. Company research found that very few beer consumers were even aware of the boycott. Even those who knew about it were seldom persuaded to avoid the product, except in certain union areas where anti-Coors activities made the brand socially unacceptable. Fewer than 4 percent of retail accounts were refusing to sell the brand.

Furthermore, among those who were brand avoiders, the labor issues were much less often the reason than were the allegations of discriminatory practices against minorities. The AFL-CIO made these issues the centerpiece of its campaign, and though

Coors and its workers strongly denied the accusations, they had some effect in the

African-American and Hispanic communities, which are important markets for beer.

Still, sales were rising. Coors moved into new states successfully despite

AFL-CIO activity to discredit them there.

(By 1989, the company served all fifty states plus several foreign markets.) Public relations counsel concluded: “The boycott is not working in the marketplace, but it is very successful in the headquarters at Golden,

Colorado.” Stronger efforts were called for.

THE NEW APPROACH PAYS OFF

The sequential phases of disarming critics, going public, and reaching out for the national market had major punctuation marks: 5

1.

Coors signed a National Agreement with a Coalition of Hispanic

Organizations, giving assurances of employment, training for management roles, increased number of

Hispanic distributorships, increased use of Hispanic vendors and services, and a minimum of $500,000 annually to be spent in public service programs in the Hispanic community.

2.

Earlier, Coors had entered into a

National Incentive Covenant with the National Black Economic

Development Coalition with much the same assurances and objectives.

In both cases, company actions were linked to assistance in its marketing efforts from the other party—quid pro quo.

3.

The company undertook diversification into gas and oil exploration, snack foods, transportation, and occupational health.

4.

New products included Coors Extra

Gold, George Killian’s Irish Red Ale, and Herman Joseph’s Original Draft.

5.

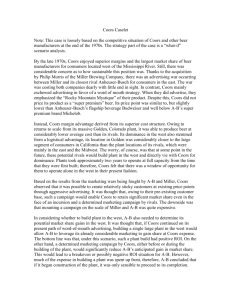

Plans were announced for the creation of a second brewery, located in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia

(See Figure 6-2) which began operations in 1987. The company added another brewery in 1990, which is located in Memphis, Tennessee.

6.

An annual report displayed a statement of corporate philosophy. It was titled “Our Values” and summarized as “Quality in all we do and are.” This became the theme of communication efforts.

7.

Coors’s V.I.C.E. Squad volunteer program (Volunteers In Community

Enrichment) was recognized as a model for linking employees, retirees, and their families with community

5 Typical of the openness in present-day public relations at Coors, we were supplied a generous bundle of information for this case. There were no questions designed to make sure we were a “friendly” medium and no defensive ruse such as “we’ll be glad to check your case study for accuracy.” We are indebted to Marvin “Swede” Johnson,

Vice President of Corporate Communications for the information provided for this case.

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

177

FIGURE 6-2 The Shenandoah Valley brewery at Elkton.

(Courtesy of Adolph Coors Brewing Company.) needs. So well received was the activity that a new adjunct group was established for people who had no connection with the company.

8.

Coors’ Wellness Program, created in

1981 by Bill Coors, was honored in

1992 with the C. Everett Koop

National Health Award for commitment to health and wellness as a priority for employees.

9.

The 10-millionth visitor took the company’s highly personalized plant tour in May 1988.

10.

In 1987, Coors became the first brewer to target women specifically in full-page magazine ads (See Figure 6-

3). A major women’s program that increased awareness about breast cancer won awards and showed that allegations of bias were unfounded (See

Figure 6-4).

There was more. The year 1987 was a busy one in Coors’s public affairs. Joe Coors took a turn as a witness in the Iran-Contra

Congressional hearings and testified that he had contributed $65,000 to Colonel North’s supply operation for the Nicaraguan rebels

(or freedom fighters, if you prefer). Finally, the AFL-CIO was persuaded to call off its 10year boycott in negotiations, led by Peter

Coors, based on carefully crafted public relations strategy that has served to deter any follow-up national boycotts to date. Joe Coors,

Sr., announced near year end that he was planning to step down from day-to-day operations. He remained within earshot as vice chairman, while his brother Bill remained chairman. But actual management was passed to Peter and Jeff, both sons of Joe.

Joe Jr. began moving up into top ranks.

These new faces have been well received, and under their management the company

178

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

FIGURE 6-3 Settings for women in Coors ads suggest energy and activity, not necessarily sensuality or submissiveness.

(Courtesy of Adolph Coors Brewing Company.)

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

179

FIGURE 6-4 Coors’s breast cancer awareness program, High Priority, encouraged women to do monthly breast self-examinations.

(Courtesy of Adolph Coors Brewing Company.)

180

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

PERSONALITY, VIEWS, AND PRODUCTS

A recurrent question in organizational public relationships is the extent to which the personality (abrasive or charming), the political affiliation (liberal, moderate, or conservative), or the views on controversial issues (such as birth control, privacy, and the public’s right to know) influence consumer purchase decisions.

Do they or don’t they?

Domino’s Pizza experienced a boycott similar to Coors’s. The National

Organization of Women (NOW) claimed that Domino’s CEO Tom Monaghan discriminates against women, by funding programs that attempt to eliminate reproductive choices. This allegation arose when Monaghan donated $50,000 to a Michigan ballot measure outlawing tax-funded abortions. NOW spokeswoman Madeline Hansen emphasized

1 pr reporter, Vol. 32, May 29, 1989: pp. 2–3.

2 Refer to Case 9-5, Dayton Hudson, for further study.

awareness as the focus of the boycott.

“We’re not telling people not to buy his pizza, but we are telling them where their money goes when they do.” 1 In response to this charge, Domino’s defense was that

Monaghan’s donation was a personal contribution.

In every locality, there are prominent, outspoken individuals whose conduct of their businesses, views on public issues, and displays of personality and character constitute mixed, if not confused, public images. It would be helpful to their public relations counsel to know whether, and under what circumstances, their expressions and actions unrelated to business adversely influence customer purchases of their products or services.

Research among customers, noncustomers, and critics might provide a clue.

2 has prospered despite a bad economy and a flat beer market. Coors is now the third largest brewer in the United States. Not too bad for a company some predicted a few years earlier would fail when it was targeted for the longest-running boycott in recent history.

■

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1.

List all the reasons you can think of why a company’s reputation, or its executives’, influence the sale of its products or services. Then list all the reasons why it does not. Do you conclude that when people reach for a

Coors they are thinking of the company’s reputation—or merely con-

2.

cerned with quenching their thirst?

Or both?

Some companies, such as Coors and

Ford, have the founding family’s name on the door. What discipline does this identity demand from members of the family, especially in terms of public relationships? What problems might

be created for public relations staff?

Overall, is this situation an advantage or a disadvantage in operating the enterprise successfully?

3.

What types of reactive strategies could have been developed by Domino’s in response to NOW’s allegations of dis-

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

181

crimination? What proactive strategies would help prevent future crises?

4.

Can a prominent businessperson, whose fortune came from the business, distinguish “personal” actions from those of the company? Why or why not?

182

CHAPTER 6 Consumer Relations

CASE 6-2 TEXAS CATTLEMEN VERSUS

OPRAH WINFREY

On April 16, 1996, Oprah Winfrey, host of

America’s top syndicated talk show, featured a former cattle farmer named Howard

Lyman, who was invited as part of the

Humane Society’s Eating with Conscience

Campaign. On the show, Winfrey and

Lyman discussed the Bovine Spongiform

Encephapathy (BSE) disease—a deadly disease that had been found in British cattle.

Just a month before the show, the British government had announced that 10 of its young citizens had died or were dying of a brain disease that may have been a result of their eating beef from a cow sick with mad cow disease, a similar dementia. An article in The Nation magazine quoted a scientist who headed the British government’s

Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory

Committee saying that millions of people could be carrying the disease, and that it is fatal and undetectable for years. When it does appear, it emerges as an “Alzheimer’slike killer.”

In the Winfrey interview, Lyman compared BSE with AIDS and raised the possibility that a form of mad cow disease might exist in the United States. He also explained that the common practice of grinding up dead cows to use as protein additives in cattle feed may have contributed to the outbreak of BSE.

Winfrey seemed clearly shocked by what Lyman said. At one point she asked,

“. . . you say that this disease could make

AIDS look like the common cold?” Lyman replied “Absolutely.” Winfrey replied, “It has just stopped me cold from eating another burger.”

The audience applauded in approval.

But Wall Street did just the opposite: The price of cattle futures dropped and remained at lower levels for two months.

The cattle industry was enraged at

Winfrey and Lyman for what they viewed as defamatory and libelous remarks. Texas rancher Paul Engler of Amarillo, Texas, along with a group of other beef ranchers, immediately filed a $12 million lawsuit against Winfrey, her production companies, and Lyman, claiming they violated the Texas disparagement law, otherwise known as the

“veggie libel law.” Passed in 1995, the law attempts to protect farmers and ranchers against false claims about their products that could unnecessarily alarm the public and hurt industry sales. According to the law, the plaintiff must prove two things: that the statement(s) made were false, and that the person who made them knew they were false.

There has long been an adage advising against making war against “those who buy ink by the barrel” and it should be extended to those who have hours of television time at their disposal every week. While the case against Winfrey and Lyman proceeded through the courts of law, it really heated up in the court of public opinion.

Battle lines were drawn early and included comments from industry groups such as the National Cattleman’s Beef Association and the American Feed Industry

Association supporting the cattlemen and consumer groups venting via publications ranging from USA Today and The Nation.

Issues such as “free speech” and the First