“Fore”tunately, with a Little Preparation

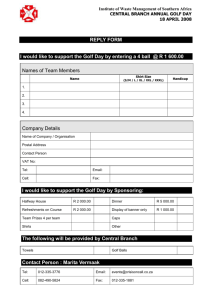

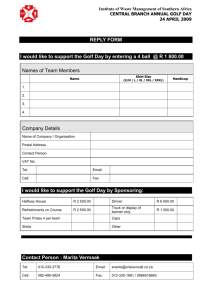

advertisement

THIS ARTICLE WAS PRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM David B. White, Esq., chair of the BWH Golf Group “FORE”TUNATELY, A LITTLE PREPARATION GOES A LONG WAY IN REDUCING LIABILITY FOR ERRANT GOLF BALLS. While baseball is fast losing ground for Americans’ hearts, golf is gaining ground quickly. As interest increases, so do liability concerns for course owners due to the American public’s propensity to sue. This phenomenon can be frightening for golf course owners whose business revolves around people using their property to hit small balls long distances (often without conceptualizing their probable destination). Any number of things can go wrong when a golfer steps up to the tee box, but with a little pre-emptive planning, a course owner should have only slight worries of liability for errant golf balls. The majority of suits arise from three groups of people: 1) players and spectators on the course; 2) passersby; and 3) neighboring homeowners. While these issues demand careful attention, adherence to a few simple rules regarding each category can save the course owner from many headaches. PLAYERS ON THE COURSE Golf is a dangerous sport. Every court in the country recognizes that there are inherent risks in the game. Nevertheless, that risk does not have to mean guaranteed liability for the course owner.i Whenever a person is invited onto someone else’s land, there is an increased potential for liability. Most states consider golf participants and spectators to be a business invitees; a business invitee is one who is on the owner’s premises for a purpose mutually beneficial to both parties (golfer pays the course owner to play golf).ii This relationship increases the duty of care that the course proprietor owes to the person on the property. The property must be reasonably safe, which requires the 1 owner to minimize the risks of golfing without altering the nature of the sport.iii He should use reasonable care in designing, maintaining, and policing the course to protect from unreasonable risks of foreseeable harm.iv This could mean either safe design and maintenance of the course or reasonable restriction of negligent golfers from the course.v As a general rule, golfers do not create liability for themselves or the course when they hit errant shots. Any person on the course is normally considered to have assumed the risk inherent in golf since “it is a matter of common knowledge that the performance of a golf ball when struck from a tee by a player using the appropriate club is completely unpredictable.”vi An analysis of negligence in this instance hinges on the standard of care imposed upon golfers and course owners.vii Course owners must exercise ordinary care, and the doctrine of “primary assumption of risk” usually precludes an injured party from recovering damages.viii Under this doctrine, the course owner and the golfer are determined to owe no duty to the injured party (golfers owe children a duty due to children’s lower mental awareness; course owners must make sure children that are too young are out of the danger of golf).ix Careless conduct of others is treated as an inherent risk of the sport.x The majority of states apply a standard of care that incorporates normal negligence into the inherent risk of the sport; the duty rises as the sport’s risk decreases.xi It is only when the conduct is intentional or approaches that of recklessness that a duty of care arises during golf; this is determined by reference to rules and customs of golf.xii If a person hits a shot pursuant to the rules, however bad or mishit, most states will find that person or the course owner not liable for any injury the golfer causes to other participants or spectators.xiii This rule extends to actions that are not “strictly” within the rules; any 2 customary shot, such as a “mulligan” (unless unannounced) will be considered not subject to liability. There is a caveat: a few states will look into ordinary negligence of a golfer and impute liability without finding reckless or intentional conduct.xiv In those states, a golfer who takes very little care in his shot, or swings without proper lookout will potentially subject him or herself and the course owners to liability. Additionally, a course owner may be subject to liability for negligent design of the course. Typically, the course owner owes no duty to golf participants or spectators due to the effect of primary assumption of risk. But, a duty arises when a course owner fails to maintain or design a course in a reasonably safe condition.xv The duty is to minimize risk without changing the nature of the game.xvi “Precautions in design and location, in the form of play or in protective devices may be required as a safeguard against injury.xvii One court has said that a course owner might have been negligent in not updating scorecards to read the property distance.xviii In that case, a golfer hit his tee shot because he believed the golfer in front to be a safe distance away. This was not the case, and the golfer was hit. Nevertheless, a course owner is not liable for physical harm to golfers by any “activity or condition on the land whose danger is known or obvious to them, unless the possessor should anticipate the harm despite such knowledge or obviousness.”xix A course with fairways, which are closely placed, could be negligently designed if coupled with other defects, but the Federal District Court of Maine stated that there should be no liability merely for close fairways.xx The harm of closely situated fairways is one that is apparent to most golfers as many courses are positioned within the confines of limited space (within a golf development or within an urban setting). Design issues usually turn 3 on the circumstances of a given situation, and a jury will usually make the determination of whether a course owner is liable for negligent design. Further, a course is potentially liable to licensees for errant golf balls. A licensee is one who desires to be on the premises of another because of some personal unshared benefit and is merely tolerated on the premises by the owner.xxi In Danaher v. Partridge Creek Country Club, the Michigan Court of Appeals found a course owner liable for a licensee’s injuries when he was struck by a golf ball while observing a pond on the course.xxii The court concluded that a course proprietor is liable for injuries to licensees if: 1) he knows or has reason to know of a condition, 2) should realize that it involves an unreasonable risk of harm, 3) should expect that they will not discover or realize the danger, 4) he fails to exercise reasonable care to make the condition safe or warn the licensee of the condition and risk, and 5) the licensees do not know or have reason to know of the condition and the risk involved. In a similar case, the Third Department of the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division found a course owner liable for injuries a man sustained from a golf ball while in the course’s parking lot. The lot and entrance road were situated in a parallel position to a tee and fairway. The court found liability because the course owner had notice that balls landed on the parking lot from the tee and the location and design of that hole arguably created an unreasonably dangerous condition and increased the risk of injury to people in the lot.xxiii PASSERSBY Passersby pose a difficult dilemma since there are two situations that arise with them. The most common situation is where a golf course is situated in a city park or golf 4 development, through which roads run. The second is where a road or highway runs adjacent to but, not through, a course. When roads traverse a course or the park or development around it, it is usually abundantly clear that golf is played there. One can see people walking with golf bags or driving golf cars and hitting balls around. Here, course operators would only be liable for an injury occurring on a nearby road if the design and maintenance of the course presented an unreasonably dangerous risk to non-golfers. However, even if a dangerous condition is present, a person with his head in the sand who is injured cannot recover. In a case earlier this year, the Louisiana Supreme Court stated that an open and obvious condition could not be unreasonably dangerous.xxiv The court found that course operators owed no duty to a passerby who was struck in the groin because he had notice of the possibility of danger (he visited the park previously and warning signs were posted).xxv The court further found that the course owners could not have foreseen the accident since this was the first injury in that location in 75 years of operation.xxvi There will always be some risk associated with playing golf, and courts will weigh the benefits versus the potential harm and cost of prevention. In the Louisiana case, the public park with four million users and one incident in that location in 75 years was determined to benefit more through its use as a golf course, and any cost of preventive measures would far outweigh the burden of such an unforeseeable risk of injury.xxvii In the situation where a course is located adjacent to a public highway or road, the liability question is slightly more questionable, and the scale has tended to tip toward public safety in use of roads rather than the benefit of the property’s use. Since 1924, the 5 courts have wrestled with the question of liability for injuries to innocent passersby.xxviii Often they have conflicting opinions, but some general rules have emerged. A course owner has a duty to take reasonable precautions for the protection of the traveling public.xxix In 1950, a Delaware court held that a landowner only has to take those precautions, which the inherent nature of the game and past history in that location make necessary for the protection of the person lawfully using the highway.xxx That court found a baseball park operator liable for nuisance when two or three balls per game landed on the highway and in the case being decided, shattered a windshield injuring a young woman.xxxi In 1933, a lower level New York court found a course liable for nuisance and negligence where a sliced ball injured a young girl riding in a car on an adjacent highway.xxxii There, the hole was situated parallel to the highway so that a right-handed golfer would hit the road if he sliced the ball.xxxiii The court noted that it was not necessary that the course owner “should have notice of the particular method in which an accident was to occur if the possibility of an accident was clear to the ordinary prudent eye.”xxxiv The probability of a right-handed golfer slicing the ball to the right is quite high; correcting a slice is one of the main challenges of golf. In the 1933 case, the course owners were found liable for negligent design of the course and nuisance.xxxv The design of the course made a sliced ball reaching the road within the range of natural probability and increased the risk of the game beyond that inherent in it.xxxvi And, the purpose of a highway is travel; the court stated that if one interferes with that purpose, it is nuisance.xxxvii The injured girl had the right to bodily security and the court believed she 6 should recover when she did not know the course was there or that a game was in progress.xxxviii If the club should have known or created or helped create a dangerous condition it would be liable for nuisance. The court stated that nuisance does not rest upon the degree of care used, but on degree of danger existing even with best of care.xxxix More recently, the New York Supreme Court determined that no liability rested in a golfer for a ball injuring a person on a road, but the course owner may still have been subject to liability.xl In that case, the ball traveled over or through a screen of trees, so upon jury determination the course operator could be liable for nuisance and negligent design in that instance. NEIGHBORING HOMEOWNERS In general, persons with homes adjacent to golf courses assume the risk that a ball will enter their property. However, that general rule may be put aside in instances where the seller misrepresented the extent to which errant balls would interfere with a homeowners right to enjoy his/her property or where errant balls interfere with the homeowners rights through the sheer magnitude of errant balls. An exception may also be found in instances where negligent design causes an exorbitant amount of balls to enter a homeowner’s property. The majority of adjacent homeowner suits against courses involve nuisance claims where the homeowner claims a course operator has permitted and unreasonable use that has materially interfered with his or her physical comfort or use of the real estate. Nuisance imports a continuous invasion of rights; therefore any action for nuisance cannot typically be maintained for just one occurrence.xli A recent Indiana case involved a condo that was situated in the crook of a dogleg left, which was in the path of golfer 7 attempting to strategically “cut the corner.”xlii The court found it permissible for a jury to determine whether a nuisance existed. However, nuisance is a difficult claim for a homeowner to win because an objective test is used to determine if the homeowner’s sensibilities should be offended.xliii Also, if an adjacent homeowner lived in his or her house before the golf course commenced operations, the standard he or she must meet is considerably lower because the situation was imposed on him or her ex post facto. If, on the other hand, the homeowner is part of a planned golf development or merely moved to a home bordering a course, he or she will be held to have assumed the risk of errant balls entering the property. The New York Supreme Court has said, “One who deliberately decides to reside in the suburbs on very desirable lots adjoining golf clubs and thus receive the social benefits and other not inconsiderable advantages of country club surroundings must accept the occasional concomitant annoyances.”xliv In that case, the court agreed with a prior case by stating that there was no nuisance where balls had broken a window, hit one daughter, and narrowly missed another. The court determined that a separation of 20 to 30 feet between the property and the fairway and 45 foot high trees along the border were sufficient to hold that the homeowners had accepted the risk and were indifferent to the consequences.xlv Moreover, a negotiated contract with adjoining neighbors licensing the golf course to permit balls onto the property can assist in alleviating any bad feelings between neighbors, and, in planned golf developments, restrictive covenants and easements for ball retrieval may be recorded prior to the sale of homes. A second path that an adjacent homeowner might take regarding errant balls that land on his or her property is a claim for negligent design, since a course owner has a 8 duty not to increase unreasonably the risks of golf.xlvi Neighboring homeowners are not entitled to the same protection as a traveler of a public highway.xlvii They typically assume some measure of the risk and must endure some damage, annoyance, and inconvenience by virtue of living in an organized community.xlviii SO WHAT SHOULD THE COURSE OPERATOR DO? The course operator should follow these simple rules to decrease the potential of errant golf ball liability: 1. If the course is part of a golf development, or will be part of a golf development, it is the duty of the course owner to provide a minima of residential comfort. This includes designing the course to reduce errant balls that would land in homeowner’s yards (It is understood that this can never be eliminated). 2. Any planned development should attempt to negotiate with current homeowners and create easements and restrictive covenants, which are recorded in order to reduce liability for errant balls and enable golfers to retrieve errant balls that land on adjacent property. 3. Design your course with the assistance of expert golf designers. A Texas court declined to find negligent design where the owner commissioned Jack Nicklaus to plan its redesign initiative.xlix 4. Design your course with this fact in mind: golfers slice, hook, push and pull. 5. Any hazard (bunker, water hazard, tree) should attempt to force a golfer to “aim” away from homes and roads. 6. In some cases, it may be necessary to install fencing throughout the course in order to block foreseeable shots from being directed at players on other holes (if closely situated). Remember, there no general liability to golfers on the course, but if an unreasonable risk is created by the design of the course, liability may follow. 7. Keep vigilant in locating and remedying potential hazards, and warn patrons of potential or known hazards that have not been remedied. 8. Develop policies for determining those eligible to play (age, experience, etc.). 9 9. Develop a policy and procedure for instances when a person files an errant ball. This should include speaking with witnesses, speaking with the person that hit the ball and speaking with the person injured or damaged by the ball. 10. Keep scorecard information current and accurate. Finally, there can never be complete safety from liability, but the course owner can find peace of mind. The course owner should remember to contact an attorney familiar with golf and its many issues because each situation is unique and deserves enthusiastic and personal consideration. The Burns, White & Hickton Golf Group represents our clients in evaluating and cost effectively assisting in the resolution of existing issues and avoidance of potential obstacles. The BWH Golf Group’s dedicated and experienced professionals can provide an in-depth understanding of the broad spectrum of golf course building, ownership and management issues so as to position our clients to maximize their investments. Contact David B. White, Esq., chair of the BWH Golf Group, with any golf course liability questions or concerns. Call: (412) 394-2500 or E-mail: dbwhite@bwhllc.com i Heiden v. Cummings, 786 N.E.2d 240, 242 (Ill. App. Ct. 2003). Danaher v. Partridge Creek Country Club, 323 N.W.2d 376 (Mich. Ct. App. 1981). iii Thompson v. McNeill, 559 N.E.2d 705, 708 (Ohio 1990). iv Bundschu v. Naffah, 768 N.E.2d 1215 (Ohio Ct. App. 2002). v See, e.g., Merritt v. Nickelson, 407 Mich. 544 (Mich. 1980). vi Gardner v. Heldman, 82 Ohio App. 1, 6 (Ohio App. 1948). vii Bundschu, 768 N.E.2d at 1215. viii Am. Golf Corp. v. Becker, 93 Cal. Rptr.2d 683 (Cal. 2000). Secondary assumption of risk permits an injured party to recovery something, albeit a diminished recovery. ix Bundschu, 768 N.E.2d at 1221; Gyuriak v. Millice, 775 N.E.2d 391, 393 (Ind. Ct. App. 2002); Outlaw v. Bituminous Insurance Company, 357 So.2d 1350 (La. App. Ct. 1978). x Bundschu, 768 N.E.2d at 1221. ii 10 xi Illinois applies ordinary negligence when the injured party is struck while in the zone of danger. In that case, improper swing, poor appreciation of the field in front of the golfer, no warning shout, and carelessness still would not find negligence when two holes were parallel to each other. Heiden, 786 N.E.2d 240. xii Thompson v. McNeill, 559 N.E.2d at 707. xiii Thompson, 559 N.E.2d at 707; Hennessey v. Pine, 694 A.2d 691 (R.I. 1997) (using antiquated hockey case law to justify a higher threshold to generate assumption of risk where former case stated, “the average person would not know of the danger of a puck.”) xiv As the law evolves quickly, consult an attorney to find out if your state applies an ordinary negligence standard. xv Bundschu, 768 N.E.2d at 1221, 1222; Morgan v. Fuji Country U.S.A., Inc., 40 Cal Rptr.2d 249 (Cal. 1995)(quoting Knight v. Jewett, 11 Cal. Rpt.2d 2, 15 Cal. 1992). xvi Morgan, 40 Cal. Rptr.2d at 249. xvii Hawkes v. Catatonk Golf Club, Inc., 288 A.D.2d 528, 530 (3d Dept. 2001) (citing 2B Warren, Negligence in the New York Courts: Golf and Operator of Course § 49.02[2], at 441 (4th ed.). xviii Cornell v. Langland, 440 N.E.2d 985 (Ill. App. Ct. 1982). xix Lemovitz v. Pine Ridge Realty, 887 F. Supp. 16, 18 (D. Maine 1995). xx Id. at 19 (stating that liability merely for fairways being close, without other factors of causation, seems like negligence in the air). xxi Danaher, 323 N.W.2d at 279. xxii Id. xxiii Catatonk, 288 A.D.2d at 528. xxiv McGuire v. New Orleans City Park Improvement Assoc., 835 So.2d 416, 421 (La. 2003). xxv McGuire, 835 So.2d at 421. xxvi Id. at 422. xxvii Id. xxviii Gleason v. Hillcrest Golf Course, Inc., 148 Misc. 246 (N.Y. Mun. Ct. Queens 1933). xxix Salevan v. Wilmington Park, 72 A.2d 239 (Del. Super. Ct. 1950). xxx Id. xxxi Id. xxxii Gleason, 148 Misc. 246. xxxiii Id. at 248. xxxiv Id. at 249. xxxv Id. at 256. xxxvi Id. at 253, 254. xxxvii Id. at 254. xxxviii Id. at 250. xxxix Id. at 254. xl Rinaldo v. McGovern (NY 1991). xli Hennessey, 694 A.2d 691. Without a continuous invasion, there would still be liability for trespass for one incursion, but only if the act was intentional. xlii Id. xliii Sans v. Ramsey Golf and Country Club, 141 A.2d 335, 339 (N.J. App. Div. 1958). xliv Nussbaum v. Lacopo, 27 N.Y.2d 311 (N.Y. 1970). xlv Id. at 317. xlvi Id. at 319. xlvii Id. at 316. xlviii Id. at 315. xlix Malouf v. Dallas Athletic Country Club, 837 S.W.2d 674 (Tex. App. 1992). 11