Mycoplasmal pneumonia in pigs - NSW Department of Primary

advertisement

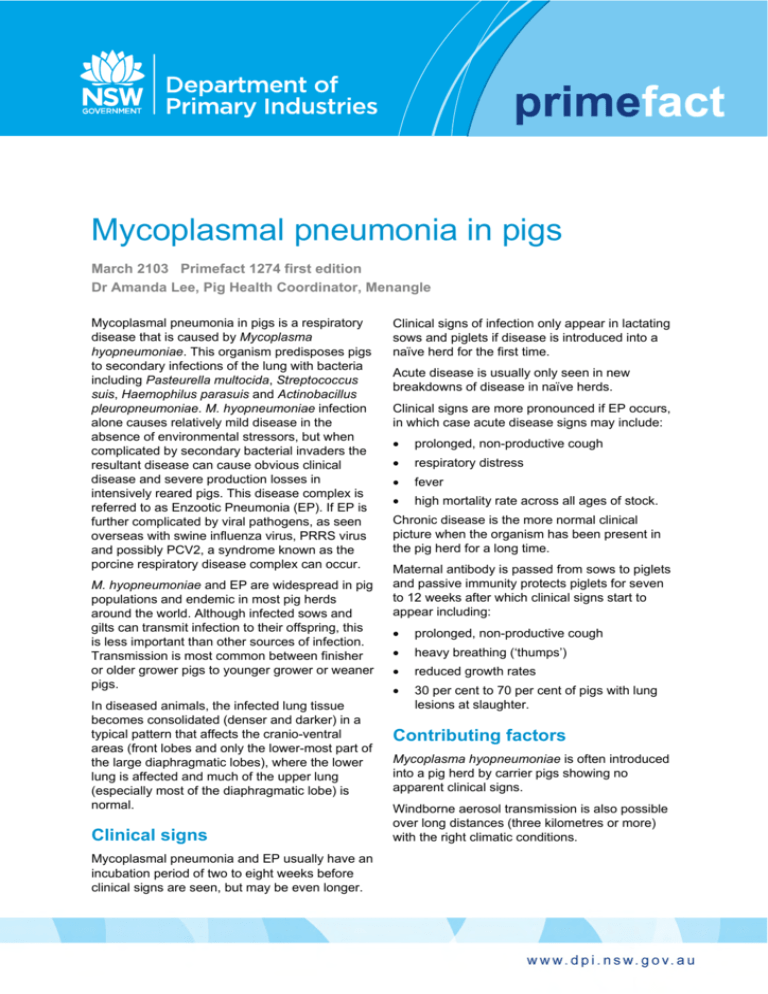

Mycoplasmal pneumonia in pigs March 2103 Primefact 1274 first edition Dr Amanda Lee, Pig Health Coordinator, Menangle Mycoplasmal pneumonia in pigs is a respiratory disease that is caused by Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. This organism predisposes pigs to secondary infections of the lung with bacteria including Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcus suis, Haemophilus parasuis and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. M. hyopneumoniae infection alone causes relatively mild disease in the absence of environmental stressors, but when complicated by secondary bacterial invaders the resultant disease can cause obvious clinical disease and severe production losses in intensively reared pigs. This disease complex is referred to as Enzootic Pneumonia (EP). If EP is further complicated by viral pathogens, as seen overseas with swine influenza virus, PRRS virus and possibly PCV2, a syndrome known as the porcine respiratory disease complex can occur. M. hyopneumoniae and EP are widespread in pig populations and endemic in most pig herds around the world. Although infected sows and gilts can transmit infection to their offspring, this is less important than other sources of infection. Transmission is most common between finisher or older grower pigs to younger grower or weaner pigs. In diseased animals, the infected lung tissue becomes consolidated (denser and darker) in a typical pattern that affects the cranio-ventral areas (front lobes and only the lower-most part of the large diaphragmatic lobes), where the lower lung is affected and much of the upper lung (especially most of the diaphragmatic lobe) is normal. Clinical signs Mycoplasmal pneumonia and EP usually have an incubation period of two to eight weeks before clinical signs are seen, but may be even longer. Clinical signs of infection only appear in lactating sows and piglets if disease is introduced into a naïve herd for the first time. Acute disease is usually only seen in new breakdowns of disease in naïve herds. Clinical signs are more pronounced if EP occurs, in which case acute disease signs may include: prolonged, non-productive cough respiratory distress fever high mortality rate across all ages of stock. Chronic disease is the more normal clinical picture when the organism has been present in the pig herd for a long time. Maternal antibody is passed from sows to piglets and passive immunity protects piglets for seven to 12 weeks after which clinical signs start to appear including: prolonged, non-productive cough heavy breathing (‘thumps’) reduced growth rates 30 per cent to 70 per cent of pigs with lung lesions at slaughter. Contributing factors Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae is often introduced into a pig herd by carrier pigs showing no apparent clinical signs. Windborne aerosol transmission is also possible over long distances (three kilometres or more) with the right climatic conditions. Mycoplasmal pneumonia in pigs Increased clinical disease is associated with the following: overcrowding continuous flow production systems concurrent diseases < 3 m3 air space per pig < 0.7 m2 floor space per pig poor air flow in pig housing variable temperatures poor insulation variable wind speeds and chilling high levels of carbon dioxide and ammonia pig movement, stress and mixing poor nutrition dietary changes at susceptible times. Diagnosis Mycoplasmal pneumonia and EP are often suspected if the clinical picture is one of coughing grower/finisher pigs with low mortality. At the abattoir, the lungs of individual pigs are scored for the amount of damage in each lung lobe. A total score out of 55 is then awarded to each pig. An average lung score is then calculated for the herd. At slaughter or postmortem examination, typical gross lesions include well demarcated dark, consolidated areas, particularly in the apical and cardiac lung lobes. Moderate Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae lung lesions with consolidation at tips of the apical and cardiac lobes. Photo courtesy of G. Eamens, NSW DPI. Very severe Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae lung lesions showing extensive consolidation of the apical and cardiac lobes and the ventral aspect of the diaphragmatic lobe. Photo courtesy of G. Eamens, NSW DPI. Lung lesions become more widespread as disease progresses, but do not extend to the upper areas of the diaphragmatic lobe unless complicated by organisms such as A. pleuropneumoniae. In complicated infections where P. multocida, H. parasuis or A. pleuropneumoniae occur, pleurisy and pericarditis may complicate the gross appearance of the lungs at necropsy. Lymph node enlargement and a catarrhal exudate in the bronchial tree often accompany these lesions, especially if EP occurs. Microscopically, there is a lymphocytic infiltration around the bronchioles and blood vessels known as ‘cuffing’. Severity of the microscopic lesions and increasing neutrophil presence is seen with secondary pathogens. Although characteristic, these pathological lesions are not specific to Mycoplasmal pneumonia or EP so does not provide a definitive diagnosis. Isolation by culture is a gold standard for diagnosis, but is technically difficult and may take two to three weeks. In herds, providing breeding stock or in certain other situations, it may be necessary to carry out further testing. Antibody detection using an indirect or a blocking ELISA is the most effective and commonly used serological test for detecting M. hyopneumoniae antibodies. Seroconversion after infection with M. hyopneumoniae is relatively slower compared with other bacterial pathogens and pigs may take eight to nine weeks to seroconvert. Therefore, testing of finisher age pigs is most useful. 2 NSW Department of Primary Industries, March 2013 Mycoplasmal pneumonia in pigs Sensitivity can be low in low prevalence herds, but specificity of the blocking ELISA is high. PCR testing can confirm the presence of M. hyopneumoniae in the nasal cavity, in lung lesions and in bronchial washings. Nasal swab PCR is the least reliable, as animals may excrete intermittently. Treatment In herds where EP is endemic, a decision to medicate feed with antibiotics (e.g. chlortetracycline, tiamulin, tilmicosin) should be made in consultation with a veterinarian and based on the following: Variable growth in pigs 10 to 20 weeks old Lung scores > 15 Evidence of clinical disease. Control Vaccination is the most effective and common method of controlling clinical disease, minimising the severity of EP and reducing transmission of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Ensure that the donor herd has maintained M. hyopneumoniae free status before moving the incoming stock into the main herd. Eradication of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae A partial depopulation is preferred by many producers in order to maintain good genetics and minimise production disruptions/costs. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae eradication is feasible and highly successful (>90%) with partial depopulations, but it is essential to plan carefully in consultation with a veterinarian and consider what other diseases can be reasonably expected to be eradicated at the same time to improve the disease status and performance of the herd. Pigs < ten months of age are often found to be highly infectious, shedding high levels of the organism and are resistant to treatment so these pigs should be destocked from the piggery during the eradication program. Maintain a broad parity breeding herd because sows > parity 2 are more immune than parity 1 sows and pass on better immunity to their piglets. Pigs > ten months of age generally have built up high levels of immunity against M. hyopneumoniae and shedding of the organism is low so these pigs can remain on the piggery during the eradication program and they should be medicated in-feed with tiamulin or a combination of tiamulin/chlortetracycline for two weeks. Maintaining a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae free herd A period of two weeks with no farrowings should coincide with the in-feed medication period and all pens should be cleaned and disinfected. Young piglets should be vaccinated as per manufacturer’s instructions. Location, regional pig density and topography are all important in maintaining a M. hyopneumoniae free herd. Piggeries that are three kilometre+ away from other piggeries in a low pig dense area with screening trees/hills have a greater chance of remaining M. hyopneumoniae free. However, overseas evidence indicates that M. hyopneumoniae can travel nine kilometres on wind currents. In addition, the pig herd should ideally be ‘closed’, introducing new genetics only by artificial insemination or embryo transfer. If new breeding stock is introduced, purchase only M. hyopneumoniae free stock from a reputable supplier and, if possible, from only one source every time. Incoming stock should be isolated for a minimum of six weeks in facilities at least one kilometre (and preferably further) away from the main herd. 3 NSW Department of Primary Industries, March 2013 Updates: www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/factsheets © State of New South Wales through the Department of Trade and Investment, Regional Infrastructure and Services 2013. You may copy, distribute and otherwise freely deal with this publication for any purpose, provided that you attribute the NSW Department of Primary Industries as the owner. Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing (March 2013). However, because of advances in knowledge, users are reminded of the need to ensure that information upon which they rely is up to date and to check currency of the information with the appropriate officer of the Department of Primary Industries or the user’s independent adviser. Published by the Animal biosecurity unit, NSW Department of Primary Industries. ISSN 1832-6668 INT12/96309 Job track 11957