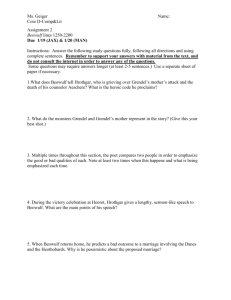

ANGLO SAXON SOCIETY LECTURE

advertisement

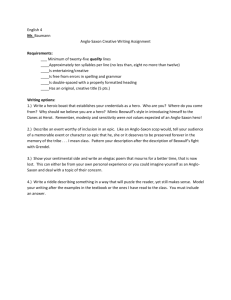

ANGLO SAXON SOCIETY LECTURE ANGLO SAXON SOCIETY LECTURE Cultural anthropologists have found that societies go through stages of development. The Anglo-Saxon society which produced Beowulf and the poems we are reading had reached the stage which is called Heroic. Much of the information you have already gathered about the Anglo-Saxons reflects the Heroic stage of their society. Heroic stage societies have the following characteristics: They are male-dominated; women are definitely second-class citizens. The upper social class is the military: kings are chosen ( or come to power on their own) based on their ability as warriors & generals. The basic social structure is that of the war-band. They are often nomadic or semi-nomadic They are often pre-literate – meaning they have not developed a written language yet (NOT that they are stupid!). However, it is not unusual for literacy to develop during the Heroic stage. They have a strong oral tradition. They are poly-theistic. They are fatalistic. Characteristics of the Heroic stage can remain “current” long after the society has progressed to other stages of development. For example, many sports teams behave like heroic societies even today. Anglo-Saxon society is based on the Three F’s: Fate, Fame & Family. FATE Like many early peoples, the Anglo-Saxons saw themselves as having little control over their lives. Besides the natural forces that could kill them at any moment, they knew that as warriors, any time they went into battle they should expect to be killed. Their philosophy of Fatalism taught them that Fate controlled when a man would die (his doom). They even personified this Fate as the goddess Wyrd (you may remember that in classical Greek mythology, Fate was personified as 3 goddesses who spun out the thread of a man’s life & then cut it when they decided he should die). Realistically, between disease and war-wounds, the average life-expectancy of an Anglo-Saxon was maybe 35 – 40. In modern terms, the Anglo-Saxons believed “We’re all gonna die,” it’s just a question of when. And it didn’t matter what a man did, when it’s his time to die, he dies (“when you gotta go, you gotta go”) – or as Tolkien put it, “A man can but die on his death day.” In other words, whether you went out to battle or stayed home & hid in the closet, if it was your time to die, you would die. However, during his (short) life, every person could choose how he wanted to behave. Since the time of his death didn’t depend on what he did, the Anglo-Saxons felt that he ought to choose behavior that would bring him Fame. (NOTE: This is a very useful philosophy for the military, since it encourages the soldiers to stay & fight) FAME For the Anglo-Saxons, Fame represented the ultimate goal of a man’s life. His whole life was centered on seeking and earning Fame. Since this was a warrior society, Fame was mostly gained by doing spectacular brave deeds in battle but one could also gain fame by being a generous and successful ruler or by overcoming natural or supernatural obstacles. Physical prowess could also bring fame. (We see all of these in Beowulf : he fights an entire army single-handed; he protects his people for 50 years as king, he swims across the ocean carrying 30 corselets, he defeats monsters and he has “the strength of 30 men in his arm.”) The concept of Fame is so important to the Anglo-Saxons, they actually had 2 different words to describe 2 different aspects of Fame: Lof: Living Fame – the praise of one’s peers & king while one is still alive. Dom: immortality – the memory of one’s greatness which continues after death, passed on in story & song by the scops. This was really the only immortality most Anglo-Saxons could look forward to, since they believed that even the gods would die. A man needed to have proofs of his fame to show to those who had not witnessed his deeds in person. Gold, armor and other rich possessions showed people how respected he was – this was his proof of lof and he would wear as much of it on his body as possible (conspicuous consumption). If he became really successful and built his own hall, he could also display his wealth there. A man also had to promote his own fame by telling of his deeds – boasting. This included both what he had already done and what he intended to do. In boasting of past deeds, he often included references to physical proofs, not only his possessions but also scars, and to eye witnesses. A wealth of detail in describing the deed also gave it credibility. Elaborate burials helped to preserve a man’s dom. The funeral service included a display of the wealth the person had amassed during his lifetime as well as eulogies, speeches or songs which recall and praise the person’s deeds. Both of these were intended to remind survivors of the reasons for the dead man’s fame while living so that they could pass it on now that he was dead. Really important men had enormous barrows built to memorialize them. This is sort of the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of a pyramid – a huge mound of earth & stone, large enough to become a landmark. The idea was that people would continue to use the barrow in giving directions – “Go to King Hagrid’s barrow & turn right” – and so the person would be remembered. And as long as his name was remembered, he had immortality. Sometimes the person was actually buried with his grave goods in the barrow but it was just as likely to be a cenotaph, an empty monument. The best way to keep one’s memory alive, though, was to have the scops compose songs about your glorious deeds. This is the oral tradition which was passed from generation to generation – with embellishments, of course! I should probably mention that these hero stories often include references to the deeds of many heroes, not just the title character (e.g. Siegemund in Beowulf). In some cases, the amount of information about a particular person which is preserved dwindles over time until the only thing left is his name & a vague reference to a battle but the Anglo-Saxons would still say that’s better than oblivion. FAMILY The core of the Anglo-Saxon social structure was the family. In most cases, the comitatus, or war-band was made up of “extended family” – cousins and in-laws, along with a few ‘outsiders.’ Most of the ‘countries’ mentioned in Beowulf – the Danes, the Geats, the Frisians, etc. – are really large war-bands and extensions of the family to clansized proportions. Loyalty to one’s family, including the extended members, was paramount among the society’s moral standards. There are 2 aspects of this concept of family loyalty which I will discuss now. 1. REVENGE CODE: Family loyalty required that any family member’s death must be avenged. (NOTE: This is one concept which continued into modern times – think of Romeo & Juliet or the Hatfields & the McCoys) This obligation fell upon the men and failure to exact revenge by killing the killer brought shame upon the whole family. There was no time limit and apparently no “extenuating circumstances”. Whether the death occurred in battle or by accident made no difference; whether the person was taking the required revenge for an earlier death didn’t either. Obviously, the “chain of vengeance” could go on forever, as feuds: each generation feeling obligated to avenge the deaths of fathers and grandfathers. To stop this before whole families were wiped out, Anglo-Saxon society developed the custom of wergild – literally man-gold. This allowed someone who had killed to ‘buy’ his way out of the revenge cycle by paying a ‘bounty’ or ‘ransom’ (the word has been translated both ways). The price would be agreed upon by the family of the victim and could be paid either by the killer or by someone who chose to help him out (as Hrothgar did for Beowulf’s father). This then satisfied the family’s obligation for revenge. Since the comitatus was considered to be an extension of the family, warriors were obligated to exact revenge for their king and fellow warriors and the king was obligated to do the same for members of his comitatus. Apparently it became acceptable to “hire a hit man” to do the avenging, since Beowulf, who is not a member of Hrothgar’s comitatus takes revenge on Grendel for Hrothgar’s warriors. Because family loyalty & the Revenge Code were so important, the worst crime an Anglo-Saxon could commit was to kill a relative. Think about it—how can the family take revenge when the killer IS family? Therefore, the whole family is shamed right out of existence (as far as society is concerned). About all they can do is disown the killer and banish him from the whole tribe (think about Romeo). Now, exile may not sound that bad, but the Anglo-Saxons settlements were surrounded by wilderness so exile meant a slow death by starvation or a quick one by wild animal attack. One indication of how seriously the Anglo-Saxons looked on this crime is that the worst insult name they could call each other was “Brother killer” It seems that deaths of women & children did not require revenge – at least it is never mentioned in the literature. Speaking of the role of women, they were definitely second-class citizens – even the queens. Among the upper class (we never hear about the peasants), women were: Conveyors of property – when a woman married, she brought a dowry to her husband. Usually, the size of the dowry was a much more important consideration than the woman herself. Part of peace treaties – daughters of kings were married off to sons of other kings on the theory that ‘in-laws’, being extended family, wouldn’t attack each other – a nice idea that didn’t always work (e.g. Hildeburh in Beowulf). Display objects – since a man needed to show off his ‘trophies’ in order to enhance his Fame, he would deck his wife in the gold and jewels he couldn’t fit on his own body. (In modern times, we call this the “trophy wife”, but the woman herself is valued.) Baby factories – of course, a wife was expected to produce sons to inherit and more importantly, keep the ancestral name alive for dom. All women were expected to marry. Their social position and security came from their husbands. Generally, the woman was considered to be a member of her husband’s family but this could lead to painful situations when her loyalty would be divided (again, see Hildeburh in Beowulf). Basically, if her political marriage did NOT prevent a war, she could have family members fighting on both sides. OTHER SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS The Comitatus This is a Latin term which was applied to the war-band, or group of warriors who followed one “king”. Generally, this started as an extended family group, with all the able bodied adult males choosing a chief to lead them. If the chief was really good at acquiring treasure and winning battles, other warriors would apply for membership and the comitatus could become a real army (see Hrothgar in Beowulf chapter 1). The comitatus gave both king and warriors opportunities to gain Fame (lof) and the treasure they captured was shared out to provide the visible proofs of that Fame. Kingship The Anglo-Saxon concept of a king is somewhat different from ours. First, one of your Introductions claims that kings were elected yet the literature suggests that kings’ sons succeeded to their fathers (Heardred follows Hygelac to the throne but only after the people’s choice, Beowulf, refused to take the job). What IS clear is that a king had to be a successful warrior in order to get and keep a comitatus. He also had to be generous to his followers, providing not only the necessities of life like food & shelter but also gold, weapons & other goodies to enhance the warriors’ Fame. A king who lived to a ripe middle age could ‘retire’ from the fighting and appoint generals, or thanes, to lead his army. (Yes, this is the same system we see in Macbeth) In return for his generosity, the king could expect total loyalty from his warriors, “even unto death.” A failure to follow the king into battle and fight to the death was considered treason and resulted in complete loss of Fame & the proofs of Fame that had been given and banishment from the tribe as well as the Comitatus (see Wiglaf’s speech after Beowulf’s death). NOTE: this is the source of the poet’s implied criticism when he says that Hrothgar’s men start “sleeping elsewhere” to avoid Grendel’s attacks & also explains Beowulf’s scorn of the “victorious Danes” & Hrothgar’s evident relief when Beowulf offers to kill Grendel. The king-subject relationship was seen as an extension of the family relationship, so all the same rules about getting revenge & not killing each other applied (so the king who “killed his drinking companions” had committed the worst crime possible, as does Macbeth) The Meadhall The meadhall was the center of social activities when the comitatus was not “on the road.” It was a large wooden structure at the center of the more-or-less permanent ‘winter’ settlement of the tribe. When the men were in camp & not off fighting, the king was expected to hold a ‘banquet’ for his warriors every night. The drink of choice was mead, which is made from fermented honey & supposedly has quite a kick but ale & beer are also mentioned. (NOTE: probably one of the reasons Grendel had such an easy time is that when he arrived, everyone was passed out drunk) Besides the obvious “male bonding” aspect of this, the meadhall banquets served several functions: They provided a forum for boasting. Warriors could tell everyone about their brave deeds. In an oral culture, ‘word of mouth’ was really the only way of letting others know what you had done, so boasting was socially acceptable as long as you had proofs (scars, witnesses of rewards). People were willing to believe you were telling the truth BUT if you got ‘found out’ as a liar, your Fame was ruined. They also provided a forum for kingly generosity. If you didn’t have witnesses to your deed, you could at least have witnesses to the king acknowledging your bravery and giving you your reward (the poet points out that “thousands saw” Hrothgar richly reward Beowulf). The scop would perform as after-dinner entertainment. There he could recite or sing the stories of heroes, which preserved their dom. He could also make up new poems honoring the men who had just been rewarded, thus furthering their lof. The Scop Actually, the Scop is important enough to deserve his own section. In a preliterate, oral culture this professional ‘poet’ was a vital institution and you find a similar kind of role in most Heroic cultures (e.g. Homer) Your Introduction calls him “the memory of the tribe”, a kind of human reference library. (I had 2 videos showing this kind of person in action. Did I give them to you?) He memorized thousands of lines of poetry and (probably) sang them to the accompaniment of some kind of stringed instrument (the Greeks used a lyre).His training began in childhood, maybe age 7, as an apprentice to another scop and he continued to learn and compose new material throughout his life. I already mentioned the entertainment aspect of his performances but he also had serious work to do. Most of his material had been passed down through generations of scops. They contain much that has little to do with the actual story that is told. This additional material: Preserves the history of the tribe, often in an indirect, allusive way. For instance, the names of kings and of important battles are listed with practically no detail as to why they are important. Teaches proper behavior by praising or criticizing the actions of various characters in the story. “This is the way a man should behave…” Teaches moral and behavioral codes to the next generation Gives immortality by preserving dom. Passes on news – many scops were itinerant; that is, they traveled from one settlement to the next, probably on some kind of circuit. They could bring information about one tribe to the members of another.While this was a very slow form of news-dissemination, it was often the only contact between different tribes other than battle. (The story of Hrothgar’s troubles takes 12 years to reach Beowulf’s tribe) The Hospitality Code This is typical of most heroic cultures. For example, Homer describes virtually the same Code in the Odyssey. Because the tribes lived in such scattered communities and strangers usually came to attack, it was important for the tribes to be able to tell friend from enemy. They developed an elaborate protocol (set of actions and responses) which was imposed on both host and visitor. (NOTE: some of these have lasted clear to the present – knocking and waiting to be invited in is one. Also, how many of you have female relatives who insist you eat something the minute you arrive ?) The guest: Wait – either outside the country or outside the meadhall -- to be invited in Disarm before coming into the king’s presence Announce himself with his name, his father’s name (family) & his king’s name (tribe) State his intentions/reason for coming Give his boast (sort of a letter of introduction) Accept food/drink as a sign of friendship Behave properly, and especially avoid violence, throughout his visit The host: Immediately offer food, drink and/or gifts as sign of friendship Provide clothing, shelter & other needs to entire party of guests Make a speech of welcome & provide opportunities for the guests to introduce themselves to his followers(establishing their lof) Protect the guest as long as the visit lasted, even if he was an enemy – The second worst crime in Anglo-Saxon eyes was for a host to kill a guest or vice versa (see the story of Finn) Only after ALL the formalities were completed could the host & guest “get down to business.” It was considered very rude to rush this procedure. MORAL CODE AND BELIEF SYSTEM The moral code of the Anglo-Saxons is mainly a warrior code. The virtues they praise are the ones that make good soldiers: loyalty to the king & comitatus as well as family, courage and steadfastness in the face of death are all basic to a successful campaign. Generosity (especially from the king & thanes) is valued because it contributes to everyone’s lof & aids morale. Even fatalism made better soldiers—if you can’t control the time of your death, what’s the point in running away? During the period which is recorded in the literature, the Anglo-Saxons were pagans. Their mythology has come down to us a Norse mythology – Odin, Thor, etc. In their basic myth, Odin and the other gods beat back the forces of Chaos, symbolized by the dragon & the wolf, to create Middle Earth, the home of Men. However, the myth also predicted that in the future, the dragon & the wolf would escape the gods’ control & destroy everything including the gods themselves. Men were the partners of the gods in holding back chaos by sheer will, courage, strength & loyalty. They saw themselves as defenders of civilization (their own world) against the wilderness, which is chaos present in Middle Earth. The fact that their myth predicted their ultimate defeat was beside the point. One offshoot of this myth was that the Anglo-Saxons were extremely nostalgic. They saw the “Golden past” as always better than the present and the present as getting progressively worse as the world slid toward chaos. Hence anything “ancestral”, that is from the past must be better than anything new. This explains the value put on ancestral weapons. It also is reflected in the literature, the elegiac tradition, which mourns the passing of “better” times and sees only death in the future (e.g. “The Wanderer”) Obviously, for most Anglo-Saxons life was (in Thomas Hobbes’s words) “nasty, brutish and short.” It’s not surprising their outlook seems pretty gloomy to us: Fate controlled their lives which were brief & violent; feuds ruined generations & whole families; war was a way of life and their gods were doomed to ultimate defeat at the hands of the forces of Chaos. It IS somewhat surprising that they still managed to enjoy life and to find beauty in the world, but they did. Their appreciation of “wrought” things like metalwork and jewelry is related to the value they put on civilization. The Big Change Of course, Anglo-Saxon beliefs underwent a major transformation when they converted to Christianity. Their new religion contradicted virtually every aspect of their old, pagan beliefs Instead of Fate, man has free will and choice The forces of Chaos (i.e. the devil) do not win; God does The focus is on an eternal life in Heaven, not ultimate destruction God may have died, but He also came back to life The past doesn’t matter because a person can repent & be better now The world will be destroyed but it will be replaced by something better – Heaven This is a much more optimistic world view and the Anglo-Saxons knew it. They looked back at their ancestors who had lived in pagan times with sympathy and pity but they still valued the courage and loyalty those people had shown. The big religious change was also accompanied by a change in their lifestyle. After they ‘migrated’ to England (read invaded), the Anglo-Saxons became less nomadic. They started to value the ownership of land and gifts of land became another reward a king could give to enhance a warrior’s lof (so Hygelac gives Beowulf “700 hides of land” as a reward for his bravery in facing Grendel & Grendel’s mother)